Not Mere Spectators > Article - Finding the Pulse of Singapore’s Identity: From EngMalChin to Multi-Civilisational An Interview with Professor Wang Gungwu

Finding the Pulse of Singapore’s Identity: From EngMalChin to Multi-Civilisational

An Interview with Professor Wang Gungwu

Siau Ming En

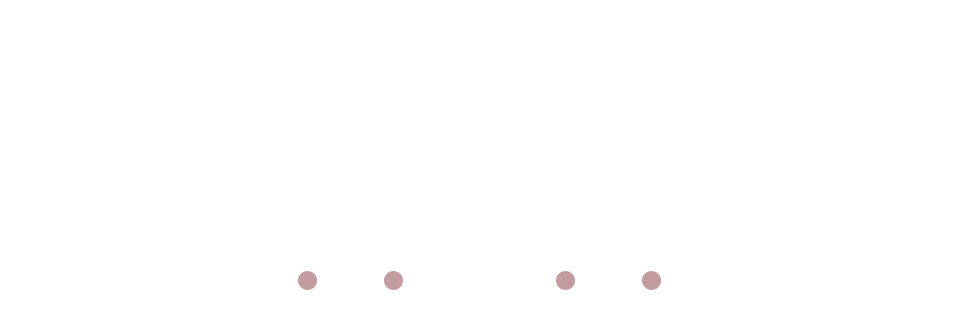

Professor Wang Gungwu, 2015.

Courtesy of Wang Gungwu.

Before becoming a renowned historian of the Chinese diaspora, Professor Wang Gungwu was a young poet searching for a literary voice that could capture the emerging Malayan consciousness.

As a student at the University of Malaya from 1949 to 1955, he met peers who believed that Malaya should have its own literature, written in a common language.1 Their interest in poetry grew first from seeing Malaya as their country, which then opened their eyes to the rich diversity of Malayan life and landscape.2 Their answer, after some trial and error, was EngMalChin—a portmanteau of “English”, “Malay”, and “Chinese”. This was a new literary language largely based on English, but mixed with Malay and Chinese phrases used in Malaya.3

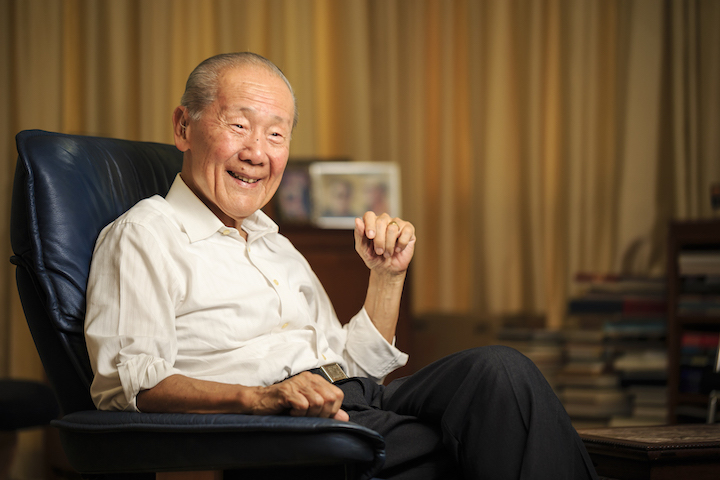

Professor Wang’s early experiments with EngMalChin were captured in Pulse, a collection of 12 of his poems published when he was 19 years old in April 1950. This modest booklet was regarded as the first book of poetry published in Singapore and would later be hailed as the beginning of a Singaporean/Malayan style of poetry.4 The EngMalChin experiment, however, proved short-lived, and Professor Wang stopped his literary writings soon after.

He eventually turned to history, exploring questions of identity through a different lens. Today, Professor Wang is a University Professor at the National University of Singapore (NUS), and Advisor to the Social Science Research Council. Among his numerous appointments, he has served as Director of the East Asian Institute at NUS from 1997 to 2007, and then as Chairman until 2018. His latest book, Living with Civilisations: Reflections on Southeast Asia’s Local and National Cultures, was published in 2023.

In this edited interview with the Founders’ Memorial, Professor Wang reflects on his early literary endeavours and his generation’s quest for a Malayan identity. Drawing from decades of research into ancient civilisations, he describes Singapore as “multi-civilisational”—a society that inherited the region’s long-standing practice of adopting and adapting values from other civilisations.

Cover page of Pulse, a compilation of poems by Wang Gungwu, 1950.

Courtesy of Wang Gungwu.

You were a student at the emergent University of Malaya when decolonisation and the building of a new nation were hotly discussed. Spirited bouts of student activism, which led to events like the Fajar trial, also made the headlines during this time. Could you tell us more about this period of your life, which coincided with post-war Malaya’s search for a new future? What kind of activities were you involved in and what drew you to them?

Coming from Ipoh, I stayed two years in the dormitories on Bukit Timah campus (occupied by the National University of Singapore’s Law Faculty from 2006 to 2025), and then for three years at Dunearn Road Hostels. That enabled me to participate conveniently in any activity that I found of interest. I was active in the Students’ Union from my freshman year, and in the Raffles Society (a cultural and literary society).

I also edited The Malayan Undergrad, acted in several plays, and enjoyed social and musical evenings organised by various other societies. In the dormitories at mealtimes and in the canteen between classes, most of our conversations were about Malaya—then still a British protectorate.

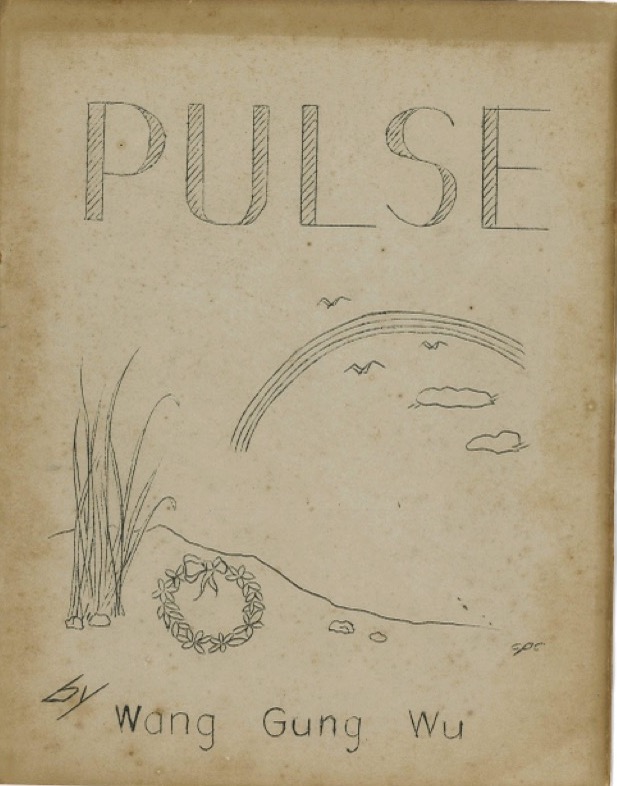

We were all conscious of the ongoing anti- communist Malayan Emergency and, in 1951, many of my close friends were detained for several months or longer. Those not arrested continued to ask for the right to organise political club, on the grounds that we should be better prepared for the various nation-building tasks that we were being educated for. Finally, in 1953, we received permission to establish one: we called it the University Socialist Club. Although I was about to graduate, I agreed to start it off as its first president. Soon after, I left the club in the hands of a younger team to concentrate on my Master’s degree.

Outside of campus, I worked part-time in various jobs, including—most enjoyably and memorably—for Radio Malaya.

Issue 9 of Fajar, the Organ of the University of the Socialist Club, with an article titled “The Emergence of South- East Asia” by Wang Gungwu listed among its contents, July 1954.

Reproduced by Special Collections, National University of Singapore Libraries.

A convocation procession taking place across the grounds of the University of Malaya, 1951.

Raffles College Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

You and your university peers created EngMalChin in the 1950s. As one of its creators, how would you define it?

Defining it is not easy because I don’t think we had any clear idea what it was.

Our generation was the first to face the question of nation-building. Until 1945, this region consisted of colonies mostly under Western powers. After World War II, they learnt there should be no more empires— every country should be a nation-state, sovereign and equal, regardless of size.

For the first generation in Malaya, this was mind-boggling. What does being a nation-state mean? How does one build a nation when it wasn’t one before? This kept my friends and colleagues excited, debating how we could prepare for the postcolonial country called “Malaya”. One of the first things that emerged was that a nation must have its own identity, which comes from what you write. If the nation has its own literature, that can be identifiable as a Malayan future.

That was how we started, though we were not very clear about what we were doing. Although it’s EngMalChin, it was basically “Eng”. The base was English because all of us at the University of Malaya were from English schools. The literature we knew was all in English. We didn’t have the imagination to think of anything else, except that English was the common language among students from the region. Yet we wanted to acknowledge that this Malayan nation must have Malay, Chinese, and other languages to reflect our mixed population.

Could you tell us more about your literary background and influences during this period?

My reading was very mixed up because of the Japanese Occupation—for three and a half years, I wandered around and could not go to school. I had no proper training in English literature except what I learnt, funnily enough, at the Department of Foreign Languages at National Central University in Nanjing which I attended from 1947 to 1948. The Chinese students taught me English literature through translations.

At the University of Malaya, we were excited to use English literature as a starting point, creating our own literature by incorporating local concepts, words, ideas, and customs to capture a Malayan spirit. The Romantics particularly captured our young imagination. The metaphysical poets interested me, except when they were very Christian, which didn’t appeal to us as none of us were religious.

Such literary influences helped us choose words to express this sense of nationhood in EngMalChin. We drew upon vernacular terms, played with Malay and Chinese words, and used what we today call Singlish. We tried to mix it all up and treat it not as weird but normal.

Did you have any doubts about whether it would take off?

Pulse came out in April 1950, but by the end of the year, I was having doubts.

At a Rockefeller Foundation writers’ course in Manila (1950), I was the only one from Malaya among the Southeast Asian guests. The Indonesians were certain and proud they had to write in Bahasa Indonesia, their national language, as it represented the independence they had fought hard for. The Filipinos debated between English, Spanish, and their own language—particularly Tagalog.

They turned to me: “You’re from Malaya but you don’t write in Malay. What’s wrong with you?” I became conscious and started questioning whether we were on the right track. I realised the language of the national literature must be indigenous to that region. That’s when I realised we couldn’t use English, that EngMalChin mustn’t be based on English. Though I continued to write in English with Malay and Chinese words, I knew this was not the future.

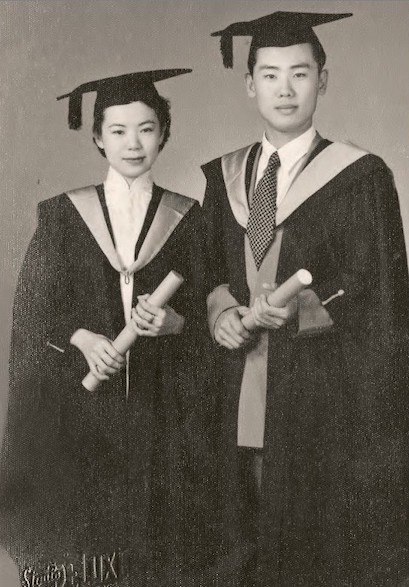

Wang Gungwu and his wife, Margaret, on the occasion of their graduation from the University of Malaya, 1953.

Reproduced from Wang Gungwu: Junzi: Scholar-Gentleman in Conversation with Asad-ul Iqbal Latif (2010) with the gracious consent of the publisher, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

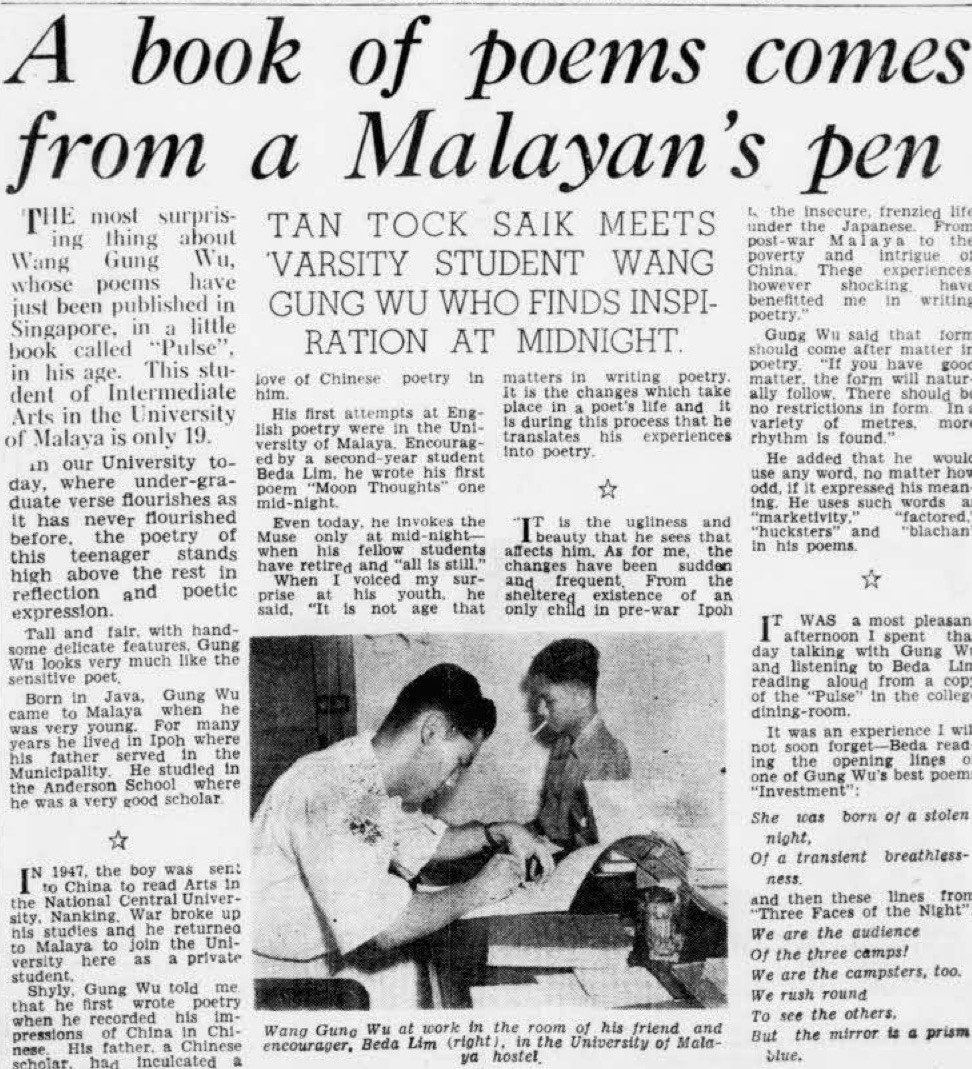

A feature on Wang Gungwu, the poet, in the Singapore Free Press, 13 May 1950.

Singapore Free Press © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

***

“Consider, as an extreme case, a young poet in Malaya... Though he knows Chinese and Indonesian, he writes by preference in English; what he really is, neither he nor anyone else knows. He is not a citizen of Indonesia, where he was born, nor of China, where his parents were born. He is not a citizen of Malaya, where he lives, nor can he, because of his race, become one. His passport says he is a ‘British-protected person.’ Actually he is a citizen of nowhere, the spokesman of nobody, the classic uprooted Asian intellectual, flotsam in the crack-up of empires, writing in a language not his own for an audience that he cannot conceive.”5

Description of Wang Gungwu by American novelist Wallace Stegner in a 1951 issue of The Pacific Spectator. Stegner conducted the 1950 Rockefeller Foundation writers’ course which Wang attended.

***

You acknowledged in a 1958 essay that EngMalChin was a failed literary experiment.6 Why do you think this was so?

EngMalChin was neither a cause nor a kind of slogan. It did stimulate discussion and debate, and that might have inspired and influenced later aspiring poets. But besides our small group, others couldn’t care less. The Chinese- and Malay-educated majority probably thought we were using English while pretending to be Malayan.

The English-educated and non-Malays were the only ones who used “Malaya”, while the Malays always used “Tanah Melayu”. Even today, it is seen as an English word created by the British. If you start with the land of the Malays, unless English becomes the language of the people, EngMalChin didn’t make sense.

Where we went wrong was being too self- conscious about nation-building and identity. Poetry was one of the things we were playing with to understand nation- building, thinking words would help us shape our identity. But we were not facing the crucial problem: the quality of the poetry. Edwin Thumboo was an exception, representing what it was like to write good poetry and letting the language take care of itself. We failed because we started the wrong way round.

If good poetry captures what Singaporeans are thinking as normal and natural, it doesn’t matter what those words are, big or small. Over time, language will eventually mature, represent Singapore, and capture the Singaporean sense of itself without being conscious of it.

I eventually gave EngMalChin up, realising this was not the way to go. I was not a natural poet, I did not set out to be one, and I still am not. Poetry was, in a way, an accident inspired by this idea of nation-building, which took us in the wrong direction.

EngMalChin may not have worked out. How else should we think about Singapore’s multicultural makeup?

I would use the word “multi-civilisational” instead of “multicultural”. In “cultures” everyone thinks their culture is the best. But in “civilisations”, values can be borrowed across borders. If one culture emphasises compassion and the other doesn’t, the latter can choose to borrow and make the value their own. That is a civilisational transfer, because values like compassion are universal and not limited to one culture or race.

Southeast Asia never had a civilisation of its own; people accepted what they thought was attractive from other civilisations. This is important—they didn’t just copy; they chose that part of the civilisation that appealed to them or suited their needs. This took place for thousand-odd years and became the culture of Southeast Asia; fluid, and based on the choices people made.

Singapore inherited this tradition of choosing from other civilisations because it didn’t have its own national culture. When Singapore became independent in 1965, it had to think about being a nation with people from different civilisations, and how they could live with and respect one another. The “multicultural” aspect of Singapore is actually “multi-civilisational”, drawn from different civilisations. The national culture of Singapore consists of different civilisations kept alive by people who are bearers of that civilisation, living and behaving as Singaporeans.

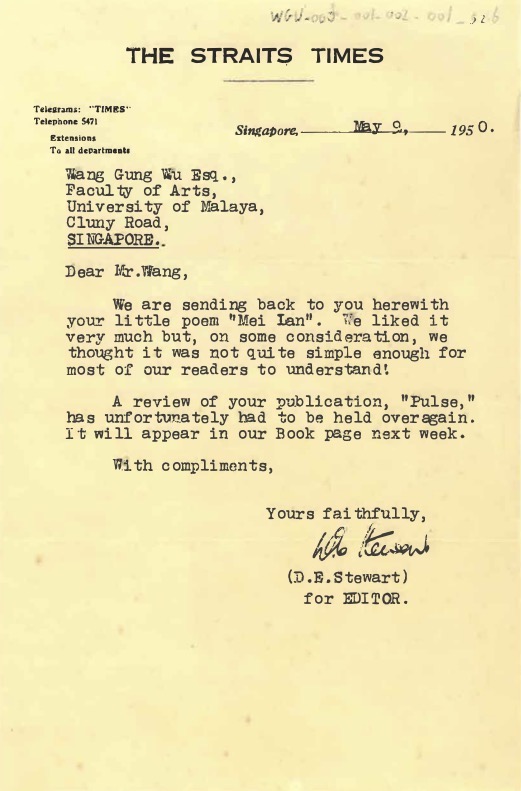

A letter from The Straits Times’ editor, rejecting one of Wang Gungwu’s poems titled “Mei Lan”, 9 May 1950.

Wang Gungwu Private Papers, courtesy of ISEAS Library, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.

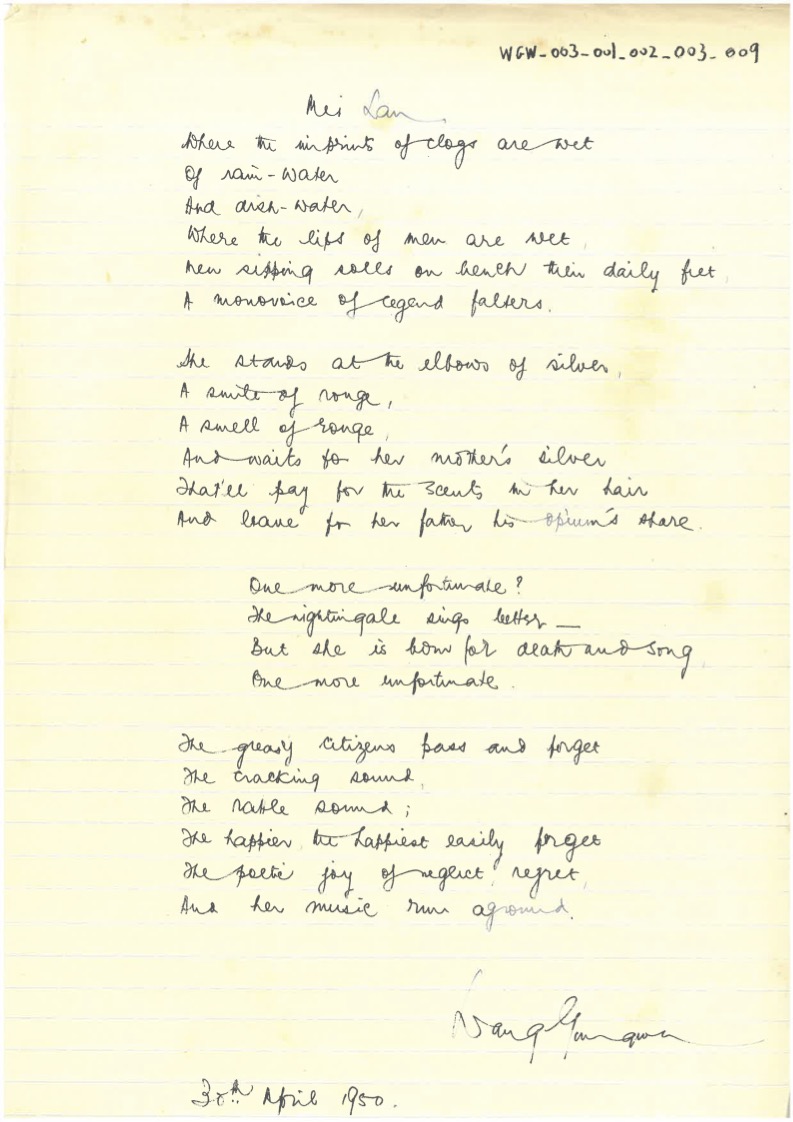

Handwritten draft of “Mei Lan”, which was rejected by The Straits Times, 30 April 1950.

Wang Gungwu Private Papers, courtesy of ISEAS Library, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.

Chua Mia Tee, KK Fresh Food Market, 1979. Oil on canvas, 68.8 × 81.2 cm. The painting captures the idea of Singapore as being made up of people from different civilisations—all of whom have learnt to live with and respect one another.

Donated by Times Publishing Limited. Collection of Singapore Art Museum, National Heritage Board.

You have described Singapore as “multi-civilisational”. How will this shape Singapore’s identity as an open and global city?

As you can imagine, it is a very delicate operation.

Singapore cannot survive without being global and searching for talent from elsewhere. It needs new migrants because our population is declining. Without people, Singapore cannot achieve its ambitions as a modern, progressive nation. To react to global events, Singapore needs diverse and the best talent in active industries and enterprises.

Singapore struggles with this and ends up creating its own class system. Some are given citizenship readily if they are very talented or invest significantly. Others come in as migrant workers. The government emphasises social harmony and cohesion, knowing how delicate it is to balance locals and foreigners. Yet this is necessary to create the Singapore identity. Singapore may never have a stable national culture in the way other countries do because it is a global city dependent on people’s mobility.

There are also tensions among the three civilisations linked to Singapore: the dominant majority Chinese in Singapore, the Muslim neighbourhood, and the dominant Western political culture. Today, the United States-China relationship represents a civilisational struggle. The Americans stand for the Western world and what they think is universal civilisation, while the Chinese stand for a civilisation they believe is necessary for survival. Meanwhile, the Muslim world is aroused by events like the situation in Gaza, which can be traced to the 1,500-year struggle between Christians and Muslims in the Mediterranean world.

The civilisational struggle in Singapore can be very intense because it is small. Phrases like “Chinese privilege” emerge because of the Chinese majority. It raises questions about Singapore’s relationship with China, which others watch carefully. Our Islamic neighbours are linked to one of the most insoluble, intractable problems of a long war and violent history. Even though the Christians are a minority in Southeast Asia, the region is affected because Muslims see even the non-Christians as part of the Western modern civilisation led by the United States and the Western Europeans, who represent the crusaders of the past.

Singapore has to be global to remain as Singapore. It doesn’t belong to any one country, culture, or civilisation. It is a mixture of civilisations within a small national set of borders, where a distinctive Singapore culture is drawn from all these civilisations. It tries to be useful to everybody in the world without taking sides. But it is not easy. I’m sorry to be so depressing in the end but I think one has to be fairly realistic about what Singapore faces.

|

“Three Faces of Night” takes readers through three distinct spaces, situated in what is likely pre-1950 Malaya: a dance hall, a city street, and a domestic space. At its core is a protagonist who searches for a reflection of his identity in a plural society.7 The poem is one of Professor Wang’s more distinctive EngMalChin pieces, in which he blends English with Malay and Chinese dialects to capture the realities of Malayan life.8, 9 |

|---|

|

Quavers quiver along the violin strings Saxon cut and Mongol shape

Let’s go to the next world –

By the drains, sandalled squats Crying, “This is our progressive Paradise.” What of the world between,

Likeliest of all

We are the audience Thus we live in triple spheres: |

|

Mix of cultural influences found in Malaya An example of Chinese, Indian, and British cultural influences. “Saxon cut and Mongol shape, Dravidian red” describe the qipao worn by the dancer. The qipao’s collar and fastening are wrongly referred to as “Mongol”; its cut refers to a tight-fitting Western dress and its bright colour is influenced by South Indian culture.10 |

|

| Mix of local languages and dialects in an English verse

“Fun” and “kuey-teow” are transliterations of types of rice noodles in the Cantonese and Hokkien dialects. “Cool-tea” is a literal translation of the Chinese term for herbal tea (liangcha).11 |

|

| Distinctively Malayan scenes and gestures

References to common scenes of people squatting by the road to eat alongside workers collecting human waste at night. |

NOTES

-

Wang Gungwu, Home is Where We Are (Singapore: Ridge Books, 2021), 35.

-

Wang Gungwu, “Trial and Error in Malayan Poetry”, The Malayan Undergrad 9 (1958): 6.

-

Lee Tong King, “A Plethora of Tongues: Multilingualism in 1950s Malayan Writing”, Biblioasia (National Library Board), April-June 2024, https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-20/issue-1/apr-jun-2024/multilingual-languages-malayan-writing-sg/ (accessed 7 August 2025).

-

Wang, Home is Where We Are, 53; Gracie Lee, “The Pulse of Malayan Literature”, Biblioasia (National Library Board), 31 January 2016, https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-11/issue-4/jan-mar-2016/pulse-malayan-literature-wang-gung-wu/ (accessed 7 August 2025).

-

Wallace Stegner, “Literary Lessons Out of Asia”, The Pacific Spectator 5, no. 4 (1951): 416.

-

Wang, “Trial and Error in Malayan Poetry”, 6.

-

Philip Holden, “Interrogating Diaspora: Wang Gungwu’s Pulse”, ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature 33, no. 3-4 (2002): 125.

-

Jonathan Chan, “Wang Gungwu (b. 1930)”, poetry.sg, 11 June 2021, https://www.poetry.sg/wang-gungwu-intro (accessed 7 August 2025).

-

Wang Gungwu, Pulse (Singapore: Beda Lim at the University of Malaya, 1950), 14-15.

-

Holden, “InterrogatingDiaspora”,121.

-

Holden, “Interrogating Diaspora”, 120.

***

Siau Ming En is Senior Manager (Curatorial & Engagement) at the Founders’ Memorial. A former journalist, she explores ways of weaving contemporary stories with historical narratives.

***

This article is featured in the Founders’ Memorial’s +65 publication, Volume 4 — the flagship publication that aims to build thought leadership on Singapore’s independence and post-independence history and society. This issue explores multiculturalism, offering broader context on its origins and evolution in independent and post-independent Singapore (1950s–1970s). Limited copies are available at the Not Mere Spectators: The Makings of Multicultural Singapore exhibition. Download your online copy here.