Not Mere Spectators > Article - Growing Pains: An Intergenerational Conversation on Language and Change

Growing Pains:

An Intergenerational Conversation on Language and Change

Ethan Ong, Ryan Ho, Liu Binrui, and Shawn Soh

Mr Ho Tong Wong and the Raffles Institution student team in conversation, June 2025.

Courtesy of National Heritage Board.

The Student Archivist Project, organised in turns by the Founders’ Memorial and the National Museum of Singapore, provides students an opportunity to engage in intergenerational conversations with senior interviewees on historical topics. The following interview, undertaken by a team from Raffles Institution in 2024, delves into the lived experience of the Chinese-educated as post-independence Singapore sought to foster multicultural unity amid the daunting threat of racial strife.

Frank, authentic, and deeply personal, this piece sheds light on the choices and challenges confronting Singapore’s ethnic majority in the aftermath of Separation—all from the vantage point of a young man caught in the crosswinds of change. From enrolling in an integrated school to grappling with a new language during National Service (NS), it highlights the everyday realities involved in forging a common space—a process demanding goodwill, mutual understanding, and at times, sacrifice.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Could you tell us more about your family and educational background?

My name is Ho Tong Wong. I was born in 1953, and I studied first in Min Sheng School (民生学校), a public primary school in Balestier, from 1959 to 1965. Later, I attended Kim Keat Vocational School, First Toa Payoh Secondary School (FTPSS), and then Thomson Secondary School for Pre-University. After completing NS in 1974, I enrolled in Nanyang University, popularly known as Nantah.

As for [my] family background, my parents were illiterate. My father was Hainanese and my mother was from Chaozhou, so we communicated at home in Hainanese or Teochew. In those days, most Chinese families communicated in dialect at home, irrespective of whether they hailed from Chinese schools or English schools.

What was the medium of instruction when you were in primary school?

At Min Sheng School, Chinese was the medium of instruction. Still, it wasn’t straightforward as there are variants in the expression of Mandarin Chinese. Take for example, the Chinese term for garbage (垃圾). In those days, my teacher would pronounce the term as lese, but when I visited mainland China a few years later, they did not understand me. Today, we have adopted the standard Chinese pronunciation of laji. However, I think people in Taiwan still pronounce this term as lese.

In primary school, every subject except English was taught in Chinese. History, Geography, and even the fiction books we read were all in Chinese. The content of these books, which included Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Journey to the West, naturally influenced us. It’s the same for your generation. Many of you enjoy all kinds of contemporary comics, and their stories will probably influence you, though in a different way as compared to my time.

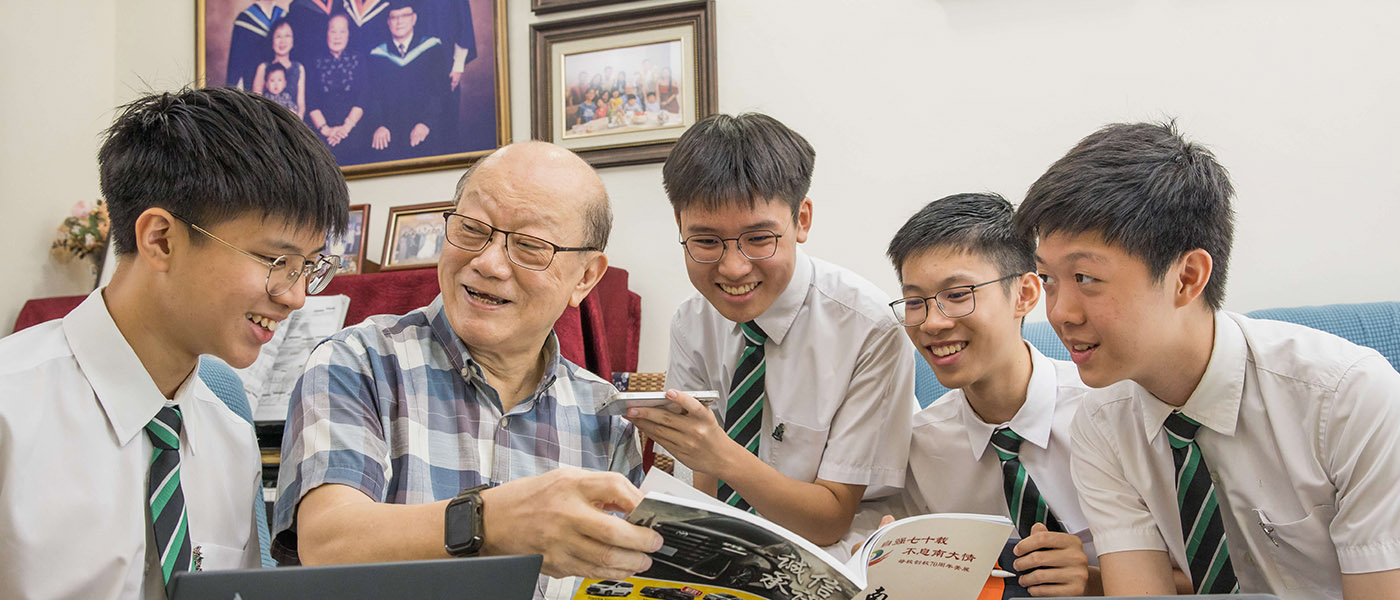

Façade of FTPSS, c1970s–1980s. FTPSS has since merged into Bartley Secondary School.

Courtesy of National Library Board.

What you’ve described about the education landscape in the 1960s seems to be the exact opposite of the situation today—since all our lessons, apart from Mother Tongue, are now conducted in English. Was there a change in the medium of instruction by the time you attended secondary school in the late 1960s?

Yes and no, as FTPSS was an integrated school. It was formed from Kim Keat Vocational School and Thomson Secondary School. That was the first time in my life that I went to a school that used two teaching mediums. The school was divided into the English stream and Chinese stream. The English stream had students from Malay and Indian households, and that was the first time I interacted with them. I attended the Chinese stream, so we didn’t attend the same classes, but we participated in common activities such as sports.

In a way, attending an integrated school broadened my worldview and outlook. I started to feel that I may not have liked the way someone behaved because of our different educational backgrounds. Personally, I felt that the students from the English stream were more westernised. They tended to talk about partying, whereas we in the Chinese stream were more conservative. Partly, this may have been because I was brought up in a traditional Chinese household, where partying and kissing girls at a young age were frowned upon. In FTPSS, we found that students from the English stream did not see such acts as out of the ordinary. They would go out on dates, and it would not be unusual.

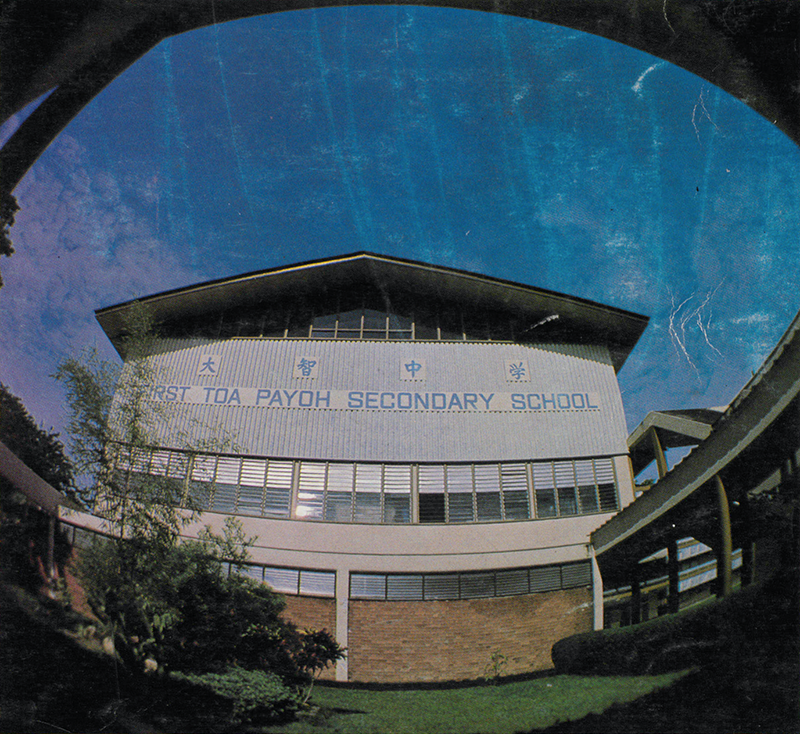

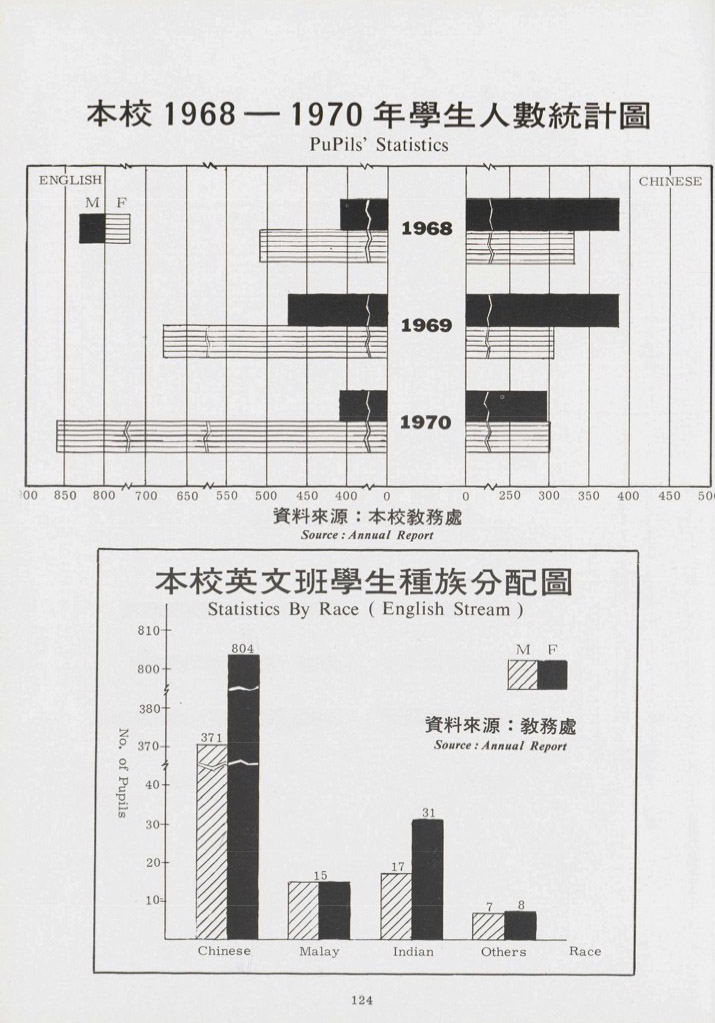

FTPSS staff photographs reflecting their assignment to either the Chinese or English stream, 1970. The images reveal that classes were ordered from A to F in both streams.

Courtesy of National Library Board.

That’s interesting! It’s hard to believe that different mediums of instruction were used within the same school. Were there any other barriers separating the students of different streams?

Initially, yes. Even where sport was concerned, the intermixing was less perfect than envisioned. For example, I was in the school’s basketball team. I would say 100% of the players were Chinese students who were Chinese-educated.

On the other hand, games like soccer and softball were dominated by the English stream. Same school, but English stream. Athletics and badminton were a better mix, where we had both Chinese and English stream students. For me, I didn’t see a problem then, because my teammates were all from the Chinese stream.

|

Integrated Schools “We have inherited four streams of education, not one, and all four are at different stages of development. It is necessary now to integrate these four into something that has a common content, purpose and loyalty.”1 Minister for Education Yong Nyuk Lin at Happy World Stadium to celebrate National Loyalty Week, 9 December 1959 From 1960 onwards, integrated schools were set up across Singapore to bring together schools of different language mediums. While students and teachers shared the same school campus and took part in sports and other extra-curricular activities together, lessons continued to be held apart in their respective language streams. The first two integrated schools were Bukit Panjang Government High School and Serangoon Garden Government High School, each enrolling 1,200 students. By 1970, 106 out of a total of 526 schools in Singapore were integrated schools, with a combined enrolment of 166,000 out of a student population of 514,000.2

Deputy Prime Minister Dr Toh Chin Chye unveiling the plaque for Selegie Integrated Primary School, with text in English, Chinese, Malay, and Tamil, 19 January 1963. Selegie Integrated Primary School has since merged into Stamford Primary School. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. |

Why do you think different families chose to have their children enrolled in different streams, and how did opting for Chinese-medium education affect you later in life?

The mix of students in the English stream mirrored the ethnic makeup of our population, with 60–70% of students being Chinese. While Chinese families initially preferred to send their students to the Chinese stream, there was a break-even point during my time in school, when the number of Chinese stream and English stream students were on par with each other. Thereafter, enrolment in the English stream overtook that of the Chinese stream as more parents opted for their children to receive their formal education in English.

My mother had initially registered me in an English-medium primary school as she took a practical view and felt that this would afford me better job prospects. Being educated in English was also seen as more prestigious. However, my father came home and was very annoyed. He stopped her and enrolled me in a Chinese-medium school. As a first-generation immigrant, he felt that our roots were still in China, and that we should not forget our own culture and language.

As for me, I did feel that the English stream students were ahead of us. Imagine if you were sent to a Chinese university and were forced to use Chinese as a learning medium. You would probably lose out to Chinese stream students! Later, during NS, I found that the students from the English stream probably had more exposure to leadership opportunities. They had the advantage of language.

In fact, it was during NS that I had to brush up my standard of English. I started off as a recruit at 6th Singapore Infantry Regiment in Tuas. I then became an instructor at the School of Artillery in Taman Jurong Camp. We were taught to fire rifles, mortars, and various kinds of equipment—all in English. So, we were compelled to learn. While I could use a dictionary to search for the correct meaning of certain words, I still found it difficult to understand certain technical terms such as “anchoring device” or “mortar director”.

Here’s an example of how bad my English was: I was told by my instructor to draw a ladder out from the store and, to be honest, I didn’t even know which object he was referring to. I went to the store and simply said, “Sir, I want to draw a ladder.” The officer-in-charge just pointed at the ladder and said, “Over there.” I said, “Where?” He said, “Are you blind? Don’t you see the big ladder there?” It was then that I told myself that I have to pick up another language. Otherwise, I would be in trouble.

Page from FTPSS’ 1970 yearbook showing (1) the shift in number of pupils enrolled in the English and Chinese streams, and (2) the racial mix of students in the English stream, 1968–1970.

Courtesy of National Library Board.

As we will all be enlisting for NS in a few years’ time, we find it particularly interesting hearing you share about your experiences. How else did NS shape you?

One formative experience was reciting the National Pledge in English. In school, we used to recite it in Chinese. But during NS, we had to say it in English. For those who could not, the instructor made us write out the sentences 100 times, so that it would be drilled into us: “We, the citizens of Singapore, pledge ourselves as one united people...” So, it was quite a big change.

This was also the first time I had to interact with other races so closely. Growing up, I never had to work with peers from the Indian or Malay communities. It was only during NS that I had to face them; I had to understand them. I didn’t even speak very fluent English. Although I understood what they said, communication was still quite a difficult task for me.

Honestly, I think NS was good for us, even though I thought it was a waste of time then. Whether you are rich or poor, whether you are Indian, Malay, or Chinese, you come to a common place. You sleep and train together, so the cohesiveness was there. During training, when you try to survive and win a battle, you won’t see any difference between a Malay, Chinese, or Indian. To use an army phrase, we tried not to sabo (colloquial for sabotage) each other. That brought us together.

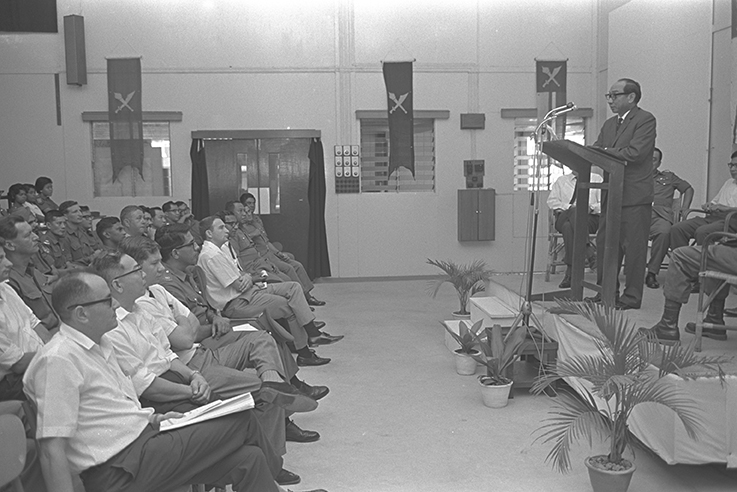

Minister for Interior and Defence Dr Goh Keng Swee opening the School of Artillery at Singapore Armed Forces Training Institute at Pasir Laba, 1 August 1967. The school later moved to Taman Jurong Camp, where Mr Ho served.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Mr Ho’s Nanyang University Graduates Yearbook, 1976–1977. He graduated from the Industrial and Business Management degree programme.

Courtesy of Ho Tong Wong.

Later, we understand you joined Nanyang University in 1974, at a time when changes were afoot to switch the medium of instruction from Chinese to English.

That was a big change for me. I studied for a degree in Industrial and Business Management, and we were learning about the term “line and staff” in an organisational context. My English- Chinese dictionary only provided a very literal translation of what these two words meant, zhixian 直线 and muliao 幕僚 (literally “straight line” and “an assistant”). This made no sense to us students.

For those who were two or three years younger than me, such as my wife, the switch from Chinese to English occurred during secondary school. So, that created a big uproar. Imagine if you have always been studying History in Chinese, but all of a sudden, the teacher is asked to teach it in English. It was an almost impossible task for them.

Looking back, however, I fully agree there was a need to have one language to unite people together. When I started working for a statutory board, I had to interact with people from all walks of life. So, I saw the value, the advantage, of mastering another language, and for English to serve as the common medium of communication in Singapore.

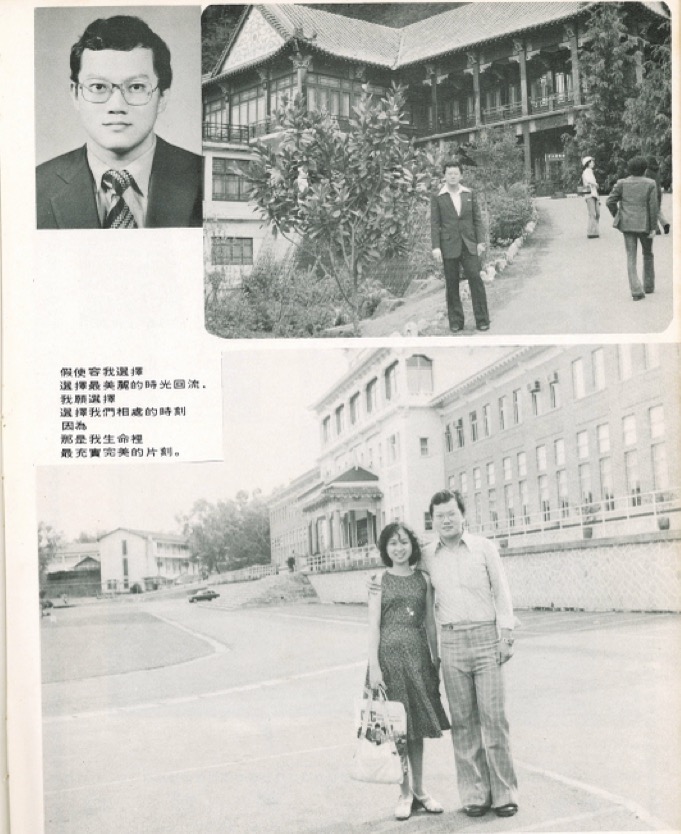

Mr Ho and his future wife outside the main building of Nanyang University, 1977.

Courtesy of Ho Tong Wong.

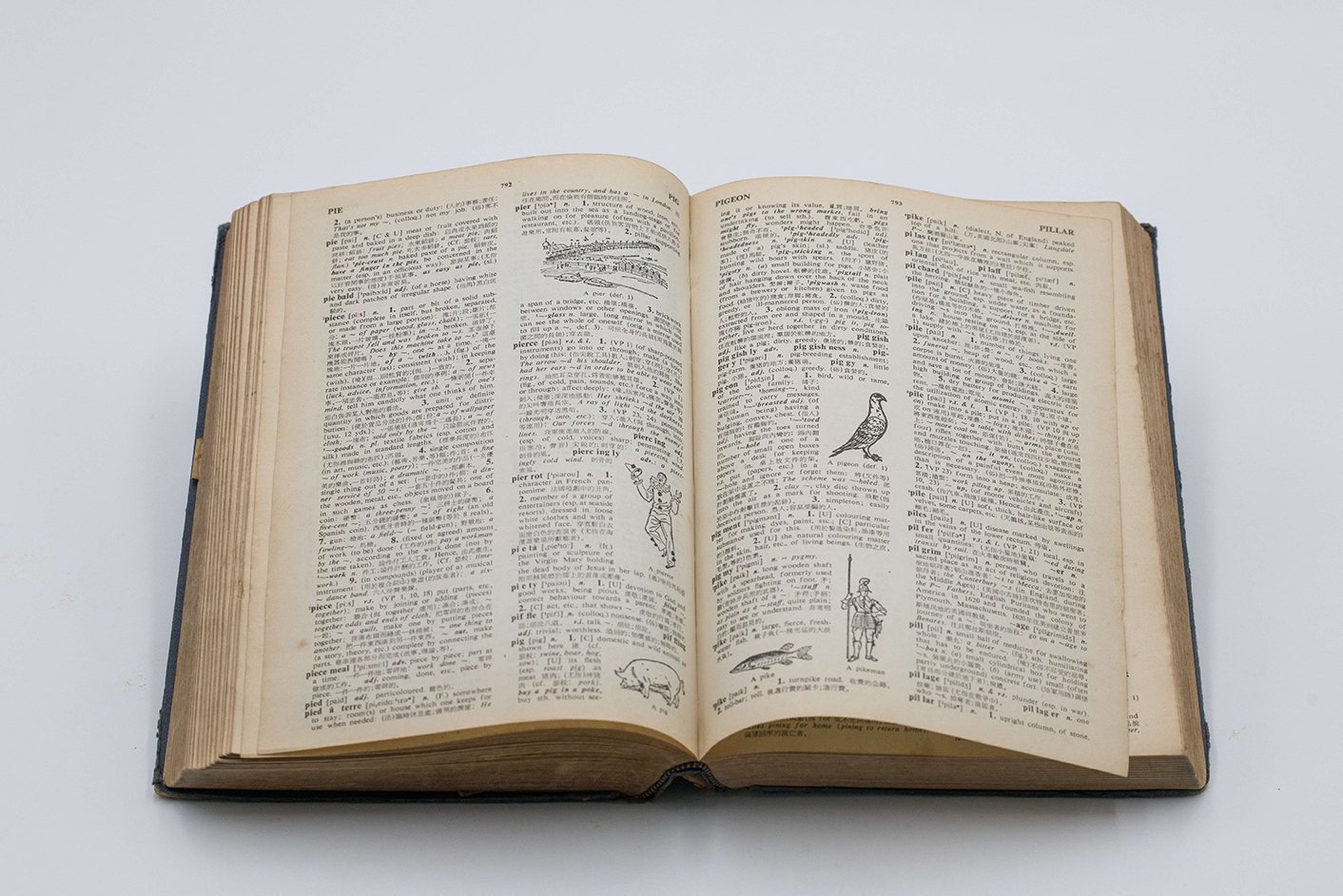

Mr Ho’s English-Chinese dictionary, which was purchased from Shanghai Book Company on North Bridge Road, 1974.

Courtesy of Ho Tong Wong.

We understand that the cohorts after you were affected by another big change: the merger of Nanyang University with the University of Singapore. As an alumnus of Nantah, did this affect you in any way?

For me, I had already graduated, I was working. I felt that Nantah had already fulfilled its historical mission. It had catered to the needs of thousands of Chinese students, fulfilling the goals set out by its founders. Times had changed by the late 1970s. Many parents were already sending their children to English schools. That was probably the time Nantah had to change. So, we had to rebuild Nantah into a university that catered to people from different streams. In a sense, I think it was a change for the better that Nantah was transformed from an academic university into a technical university where students could learn more advanced knowledge to help build the nation.

Years after the closure of Nantah, I think we can all agree that it is the Nantah spirit that lives on and is representative of the wider Singapore spirit. It is a spirit which places the interests and well-being of the community at its heart. Without government support, the community identified a need for education in the Chinese community, and proceeded to raise funds, mobilise people, and set a common goal, all with the objective of uniting people together. When the university was declared open, it was said that the traffic jam stretched all the way from Jurong to Bukit Timah. The response from the community really moved me.

Chief Minister David Marshall, Tan Lark Sye, Lien Ying Chow, and Colonial Secretary Alan Lennox-Boyd surveying the upcoming Nanyang University Campus, 21 August 1955.

The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Roof tile from Nanyang University.

Collection of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

With these changes in education and language policy, was there any point when you felt that Chinese culture was being eroded or lost?

During my time, English stream students still maintained a strong connection with Chinese culture. Many still spoke Chinese dialects at home, so Chinese cultural values continued to be passed down to them. These days, with your parents likely having been educated in English, society has become very westernised. My concern is that the younger generation may lose touch with their cultural roots.

Having experienced the ups and downs of Singapore’s nation-building firsthand, what would you say are the most important qualities our generation should cultivate in order for us to continue being a strong and prosperous nation?

I’m probably biased, but it would have to be qualities related to the Nantah spirit for me. That sense of care for future generations, coupled with a “never-say-die” mentality. In fact, these values are not exclusive to the Chinese community. After all, our forefathers came from all over the world: China, India, and the Malay Archipelago. They each made their mark by working hard, inspired by a desire to improve the lives of their children. I would encourage the younger generation to uphold these values, and to give back to society.

Watch other submissions to the 2024 Student Archivist Project here.

NOTES

-

“The Role of Teachers—By Lee”, The Straits Times, 9 December 1959, 20.

-

“The Paradox of Integration”, The Straits Times, 19 April 1970, 10.

***

Ethan Ong, Ryan Ho, Liu Binrui, and Shawn Soh are Year 4 students (2025) at Raffles Institution. This piece would not have been possible without the advice and mentorship of their teacher-in-charge, Mr Tan Shengli.

***

This article is featured in the Founders’ Memorial’s +65 publication, Volume 4 — the flagship publication that aims to build thought leadership on Singapore’s independence and post-independence history and society. This issue explores multiculturalism, offering broader context on its origins and evolution in independent and post-independent Singapore (1950s–1970s). Limited copies are available at the Not Mere Spectators: The Makings of Multicultural Singapore exhibition. Download your online copy here.