Not Mere Spectators > +65 Article - Multiculturalism by Design: The Legacy of the 1966 Wee Chong Jin Constitutional Commission

Multiculturalism by Design:

The Legacy of the 1966 Wee Chong Jin Constitutional Commission

Jaclyn Neo

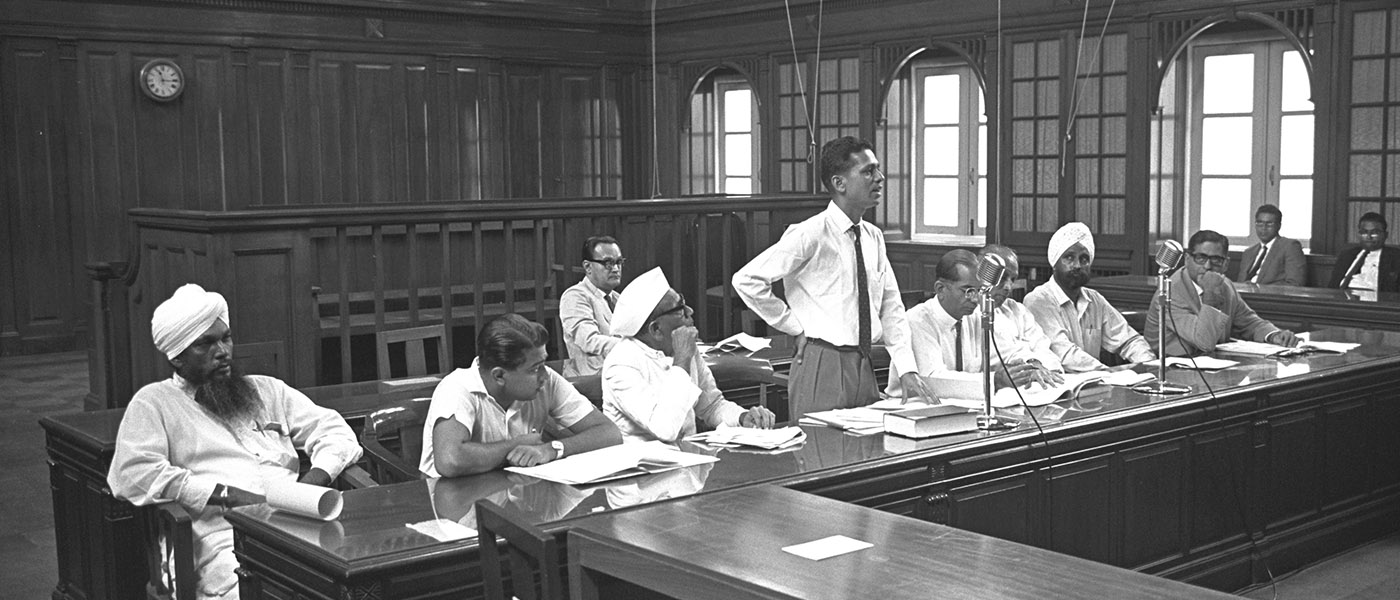

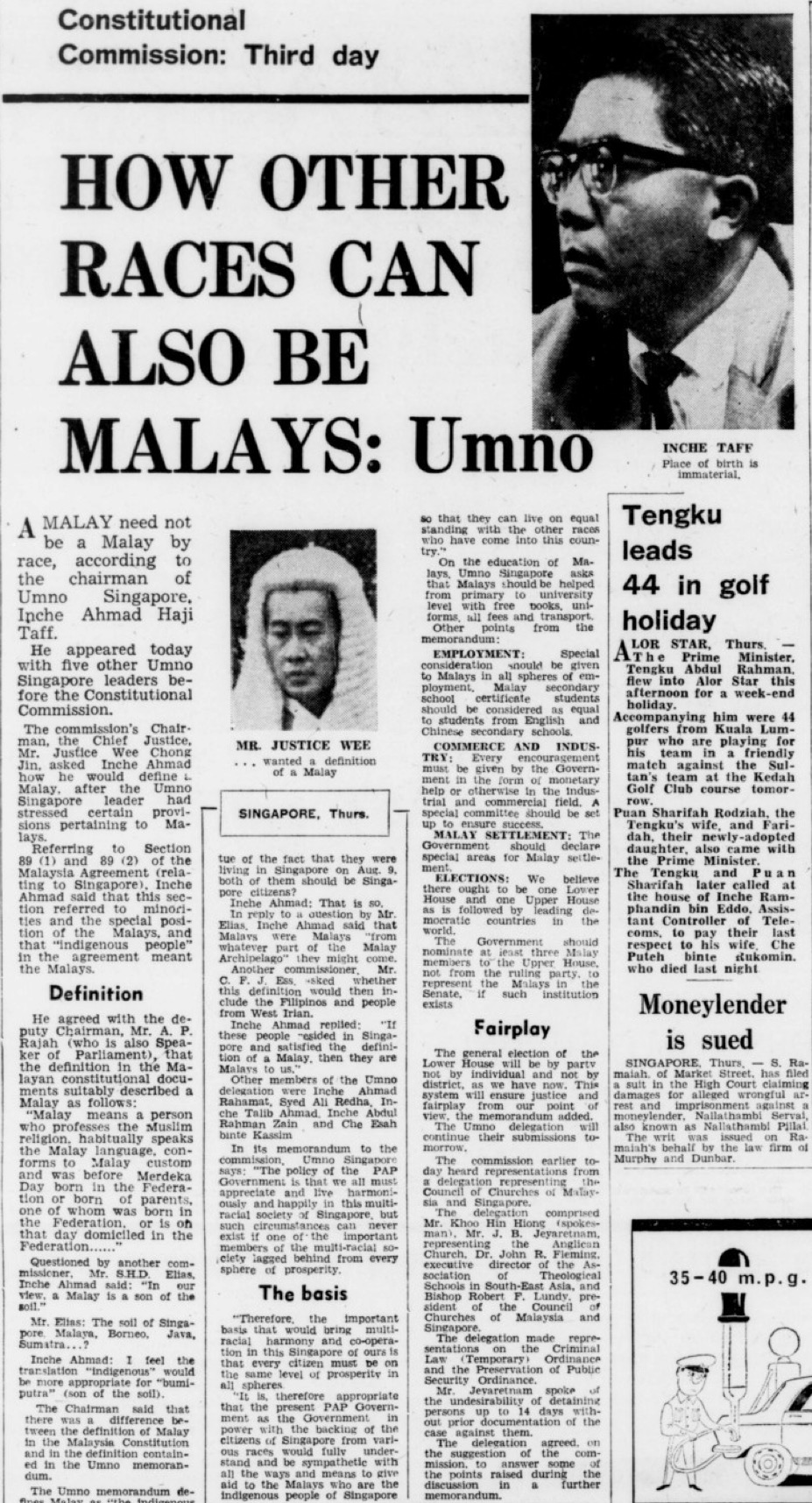

A Commission hearing at the Supreme Court, 1 March 1966.

Ministry of Information and the Arts collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

On 9 August 1965, Singapore stood at the crossroads of turmoil and promise. Social tensions were high after a brief but turbulent merger with Malaysia.1 The Federal government had emphasised Malay dominance in the peninsula, but Singapore yearned for a more inclusive, multicultural state.2 With Separation, Singapore had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to construct a nation based on this forward-looking vision. In a nationally televised press conference, Prime Minister (PM) Lee Kuan Yew declared that Singapore was to be a multiracial nation—not a Malay, Chinese, or Indian nation, but a country where everyone would have an equal place, regardless of race, language, religion, or culture.3

Convinced that majoritarianism should not take root in Singapore, the government took immediate steps to assure minority communities that their rights would be safeguarded. At the very first sitting of Parliament in December 1965, Minister for Law and National Development E. W. Barker announced the formation of a Constitutional Commission, chaired by Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, to deliberate on this matter.4 The Commission would go on to seek the views of a broad spectrum of Singapore society, but it eventually resolved that Singapore’s approach towards protecting its minorities lay in upholding individual liberties for all, as opposed to enshrining minority rights. Minister for Foreign Affairs S. Rajaratnam summarised the nub of the issue during the March 1967 parliamentary debate on the Commission’s report:

“Once a community, either based on race, language or religion, confers special rights on itself and if it happens to be a minority, then in no time the majority will say, ‘Well, since you can ask for special rights, I too will vote special rights for myself.’”5

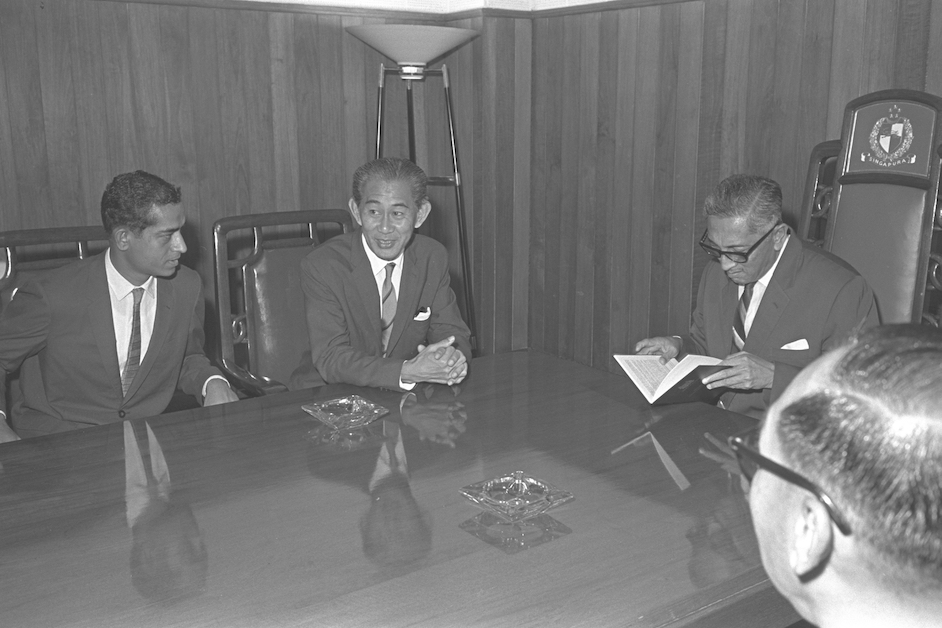

E. W. Barker taking his oath of allegiance during a subsequent session of Parliament, 6 May 1968.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Formation and Mandate of the Wee Commission

The formation of the Wee Commission was a significant milestone for independent Singapore as the newly sovereign nation-state had no ready-made Constitution to turn to. Instead, the Singapore Constitution was initially an amalgamation of parts of the Malaysian Federal Constitution with the 1963 State of Singapore Constitution and the 1965 Republic of Singapore Independence Act. Some constituent parts of this “makeshift Constitution” already contained clauses pertaining to equal protection and non-discrimination. For example, Article 12, which was taken from Article 8 of the Federal Constitution of Malaysia, expressly provided for equal treatment for all persons before the law. In addition, Article 89(1) from the State of Singapore Constitution spelt out “the responsibility of the Government constantly to care for the interests of the racial and religious minorities” in Singapore.6 Article 89(2) further emphasised the “special position of the Malays, who are the indigenous people of [Singapore]” and “the responsibility of the Government to protect, safeguard, support, foster and promote their political, educational religious, economic, social and cultural interests and the Malay language.”7

It thus fell on the Wee Commission to consider these texts holistically, guided by the following terms of reference:

a) to receive and consider representations on how the rights of the racial, linguistic and religious minorities can be adequately safeguarded in the Constitution;

b) to consider what provisions should be made to ensure that no discriminatory legislation would be enacted before adequate opportunities have been given for representation from parties likely to be aggrieved;

c) to consider what remedies should be provided for any citizen or group of citizens who claim to have been discriminated against and to recommend the machinery for the redress of any complaints;

d) to consider how such provisions can be entrenched in the Constitution.8

Before the Commission could get to work, its composition first had to be determined. According to Wee’s oral history recollections, PM Lee began by drawing up a preliminary list of names, to which Wee gave his input.9 In the end, the Commission settled on a list of 11 “eminent legal persons” which included the Speaker of Parliament A. P. Rajah, former Progressive Party Commissioner Cuthbert Ess, Muslim Advisory Board member Mohamed Javad Namazie, and Secretary-General of the Singapore United Malays National Organisation (SUMNO) Syed Esa Almenoar, among others.10 PM Lee would later make special note of how the existence of such an esteemed multiracial panel could provide “deep, psychological assurance” to Singapore’s minorities:

“The very fact that there is almost no minority group in Singapore that can say that they are not represented by someone in this Constitutional Commission who understands some part of their life and practices makes its findings all that much more valuable.”11

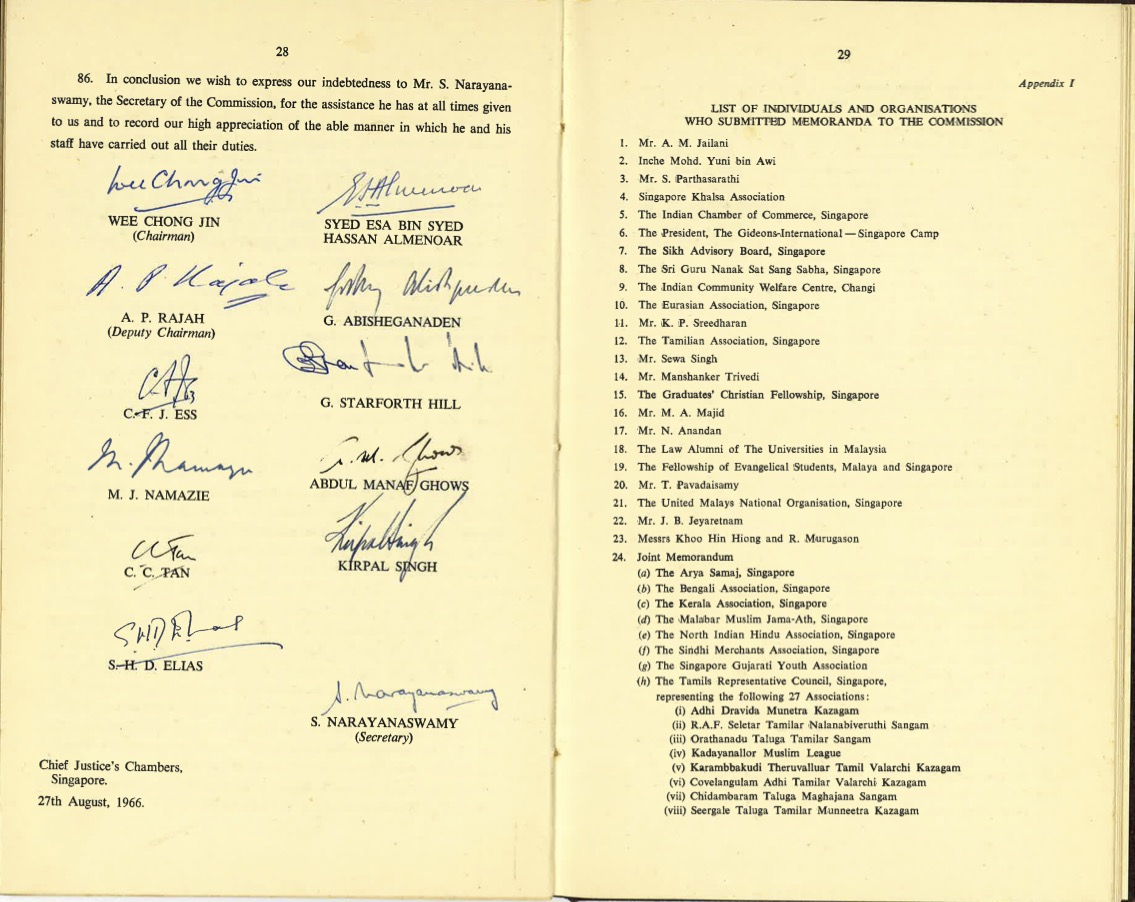

Opening page of the Wee Commission’s report, 1966.

Courtesy of National Library Board, Singapore.

Signatory page of the Wee Commission’s report, 1966.

Courtesy of National Library Board, Singapore.

Speaker of Parliament, A. P. Rajah, welcoming President Yusof Ishak to Parliament House during Parliament’s first sitting, 8 December 1965.

Yusof Ishak Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

|

Members and Secretary of the 1966 Wee Chong Jin Constitutional Commission

|

***

“My job was to represent the European community... One of the main problems we had to deal with was how to protect minorities in Singapore, because with the Chinese majority, the other minorities could get left out in the cold.”12

Graham Starforth Hill, a member of the 1966 Constitutional Commission, in a 2011 interview with the National Archives of Singapore

***

The Commission’s composition aside, public participation was key to its efforts and legitimacy. By January 1966, calls for representations to the Commission were published in major newspapers, with clear instructions on how they could be submitted (i.e. directly to the Chief Justice’s chambers in the Supreme Court building).13 Within just one month, the Commission received some 40 memoranda and held 10 public hearings.14 Groups that participated included SUMNO, the Tamil Association of Singapore, various Sikh and Indian organisations, and the Council of Churches of Malaysia and Singapore.15

Curiously, the Chinese community did not participate substantively in the public hearings that were organised, and mainstream Chinese newspapers did not report widely on the Commission’s work. The fact that the Commission was tasked specifically with looking at minority rights in its Terms of Reference was also noted by some Members of Parliament (MPs) when it debated the Commission’s recommendations in 1967. The MP for Changi, Sim Boon Woo, opined that the Commission had gone beyond its remit by enmeshing minority rights within other broader Constitutional provisions, even though the Commission had asserted that both were fundamentally intertwined:

“Sir, this House is supposed to have a Report on minority rights, but it has become a Report of the whole Constitution, as the very title itself shows. Mr Speaker, Sir, with the greatest respect to the legal luminaries who signed the Constitution[al] [Report], I say that the correct title should be ‘The Report of the Constitutional Commission on Minority Rights’. I repeat, Sir, ‘... on Minority Rights’ alone.”16

The Commission led by Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin (centre, in the Chair) presiding over hearings, 2 March 1966. Wee was the first Asian and Singaporean to head the Judiciary when he was appointed Chief Justice in 1963.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Public Participation: Key Concerns of Minority Communities

After submissions were heard in March 1966, the Commission spent the following six months deliberating the memoranda. While the Commission’s internal notes—perhaps owing to confidentiality concerns—are not publicly accessible, newspaper reports on the hearings provide a flavour of the diverse views deliberated, and the specific concerns of Singapore’s minority communities. These fell into four broad categories.

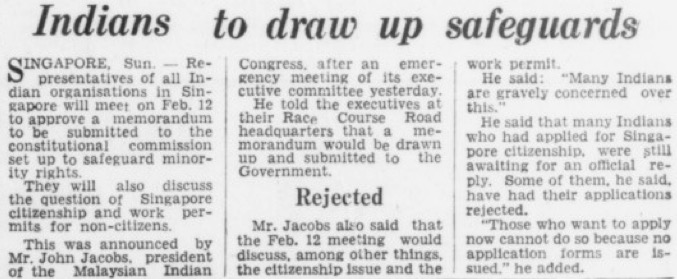

A. Citizenship and Immigration

Citizenship was the top priority for the Indian community. At the time of independence, many Indians who had arrived in post-war Singapore still had not attained formal citizenship.17 In addition, many had not initially been able to bring along their families due to financial constraints. By the time they were able to, restrictive immigration laws prohibited their spouses from entering Singapore, because they had lived separately from their husbands for more than five years, and their children were above six years old.18 The Indian representatives, led by individuals from the Bengali, Kerala, Gujarati, Sikh, Tamil, and Sindhi Associations, thus passionately asked for these laws to be reformed so that citizens would not have their loyalty “divided by [their] wife and children living in another country”.19

B. Socioeconomic Uplift and Privileges

The Malay community, on the other hand, were concerned about their economic conditions. SUMNO positioned themselves as the community’s representatives, and called for educational support (from primary to university level), job opportunities, government assistance in entering business and industry, and even designating areas for Malay settlements.20 In doing so, they alluded to Article 89(2) of the Constitution, contending that “citizens of Singapore from various races would fully understand and be sympathetic with all the ways and means to give aid to Malays who are the indigenous people of Singapore so that they can live on equal standing with the other races who have come into this country”.21 While the Commission, and subsequently Parliament, affirmed the necessity of retaining Article 89(2), some ethnically Malay People’s Action Party (PAP) MPs felt that it was equally important to reference the higher “ideals of democracy, justice and fair play”.22 Rahim Ishak, Minister of State for Education and MP for Siglap, was one of those who expressed concerns:

“The special position of the Malays can be written into the Constitution a million times, but there will be no progress if realisation and the correct mental attitude towards this special position and what it offers is not exploited.”23

A Straits Times report on the Indian community’s concerns, 31 January 1966.

The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

C. Cultural Identity and Language

The realm of culture invited equally passionate proposals. Several groups, including those from the Indian community, expressed their desire for vernacular languages like Tamil and Punjabi to be accorded greater recognition by the government.24 The most earnest representations in this regard came from the Malay community, as they grappled with the transition from majority to minority status in the new state.25 SUMNO representatives gathered before the Commission advocated for the Constitution to affirm the Malays as “the indigenous people” of Singapore, and to define a Malay person as someone “who professes the Islamic religion, speaks the Malay language and adopts Malay customs and traditions”.26 They also argued that this intertwining of race and religion was essential, noting that “if a Malay did not profess Islam, it was difficult for the Malay community to accept him”.27

SUMNO’s submissions notwithstanding, there were certainly other representors who disagreed with entrenching cultural differences. The Law Alumni of the Universities in Malaysia (the Singapore section) argued that the perpetuation of religious, racial, and linguistic features of each minority group would lead to a fragmented society. Instead, they envisaged a future Singapore where “awareness of differences in race, language and religion can eventually be subordinated to greater urges of nationalism like patriotism and good citizenship”.28

A Straits Times report on SUMNO’s submissions to the Commission, 4 March 1966.

The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

D. Religious Freedom, Electoral Representation and Political Voice, and Everyday Challenges of Minorities

Besides submissions relating to the above-mentioned areas, the Commission also heard representations on a range of other concerns. Some religious and civic groups, for example, took issue with Article 11 of the Federal Constitution of Malaysia, which prohibited religious proselytising to Muslims, and which had been imported wholesale via the 1965 Republic of Singapore Independence Act.29 The Commission would later recommend that this part of the Article (now Article 15) be left out of Singapore’s constitutional framework, given that “singling out a particular religion” for special treatment was “inconsistent” with a “democratic secular state”.30

On the political front, proposals ranging from a system of proportional representation to a separate Upper House or Senate were also discussed, as minority groups sought guarantees that they would be represented in the legislative process.31 Last but not least, the Commission also heard from smaller groups like the Seventh-day Adventists on specific laws that could unintentionally penalise religious practices outside the mainstream.32

Parliament Debates the Commission’s Recommendations

Faced with these diverse submissions, the Wee Commission crafted a carefully balanced and unanimous report that members of the House would variously praise as “exquisite” and “one of the best”.33 Parliamentary debate on the Commission’s recommendations was spirited and robust, taking place across four days in March 1967. More than 20 members addressed the House in Singapore’s four official languages, with PM Lee, Minister for Foreign Affairs S. Rajaratnam, and Malay-Muslim MPs Rahim Ishak and Ariff Suradi speaking most extensively. Central to their deliberations was the main issue that had earlier confronted the Commission: how could the fabric of a diverse nation be held together, even amid divergent and potentially competing interests?34

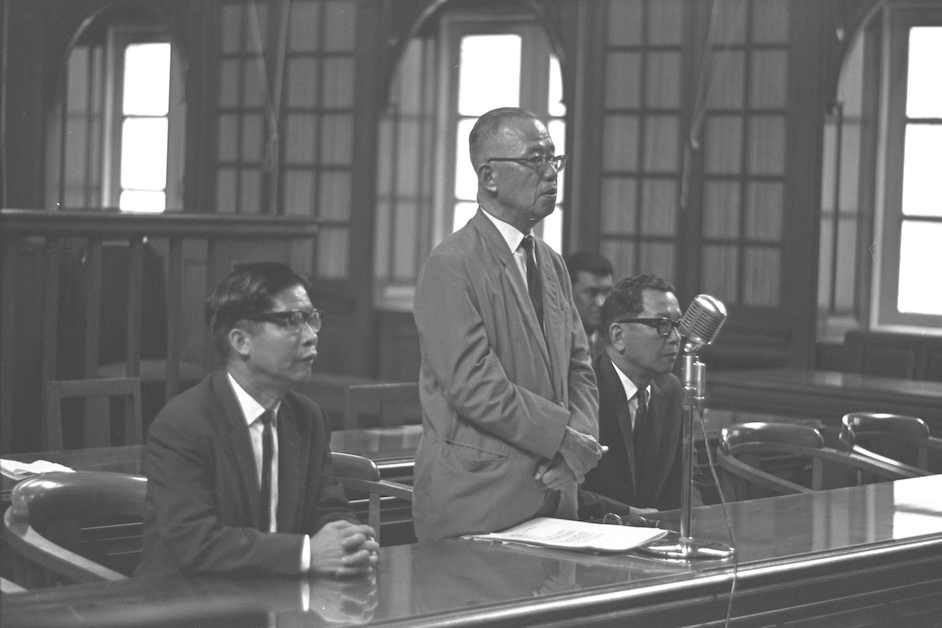

A group making its representation to the Commission, 14 March 1966.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

At its core, Parliament agreed with the Commission’s recommendation that protecting Singapore’s minorities begins with respecting individual rights. This meant entrenching in the Constitution “the fundamental rights of both the individual and the citizen (which would include prohibition against discriminatory treatment on the ground only of race, descent, place of origin or religion)”.35 Notably, this approach shifted the focus from group-based privileges to equal rights and dignity for each person. In commending this approach to multiracialism to the House, Rajaratnam astutely noted:

“Once minority communalists turn to communal politics as the only solution, then the majority community is also free to go in for uninhibited communal politics themselves.... [Rather], the best guarantee against communalism by the majority is the emergence and consolidation of multiracial parties. Only through multiracial parties can the minorities get the majority to reach accommodation with them, by compelling the majority to pay regard to the interests of all, the majority as well as the minorities.”36

Thus, Parliament agreed with the Wee Commission’s affirmation of Article 89 of the Singapore State Constitution as fundamental and vital.37 This is now Article 152 of the Singapore Constitution. It imposes a state duty, rather than grant a right that citizens can enforce in court. Nonetheless, the MP for Kampong Kembangan Ariff Suradi noted that the Government had, since coming to power in 1959, already implemented the provisions of the Article. In so doing, it had committed itself to “protecting, safeguarding, supporting, fostering and promoting the economic, religious, social and cultural interests of the Malays and the Malay language”.38

Connected to the discussion on Article 89 was the Commission’s refusal to recommend a prescriptive approach towards defining the Malay community, which it felt would be both over- and under-inclusive. Parliament endorsed the Commission’s recommendations, declining to constitutionally and legally define Malays by their use of the Malay language, adherence to Malay customs, and as Muslims. Such a definition would be over-inclusive as certain citizens who are not of Malay descent, or not born in Singapore, could fall within the definition and thereby claim a “special position” under the Constitution. The definition was also under-inclusive as it would exclude persons who consider themselves Malay but not Muslim.39 In the words of the MP for Kampong Kapor Mahmud Awang, the proposal—surfaced by SUMNO—was “confusing and misleading”.40 The rejection of such a provision further affirmed the religious freedom of ethnic Malays to choose their religion.41 This was very much in line with the Wee Commission’s refusal to retain restrictions on religious propagation under the religious freedom clause (now Article 15).

Souvenir booklet of the Singapore Constitution Exposition, 1959.

Collection of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Notably, in 1988, the Singapore Constitution under Article 39A(4) would define a person belonging to the Malay community as one “whether of the Malay race or otherwise, who considers himself to be a member of the Malay community and who is generally accepted as a member of the Malay community by that community”.42 Legal scholars Kevin Tan and Thio Li-ann have noted how this provision “avoids definitional entanglements”, by “blend[ing] the subjective element of self-identification with an objective element of community recognition”.43

The Wee Commission’s most concrete institutional legacy lies in its recommendation to establish an oversight body that ensures discriminatory legislation would be flagged before it passes into law.44 While this proposal for a Council of State initially received a lukewarm response from Parliament, with some MPs criticising its unelected nature and associated costs, it was eventually constituted in modified form as the Presidential Council in 1970.45 This was renamed the Presidential Council for Minority Rights in 1973, and its early members included Council Member of the Inter-Religious Organisation D. D. Chelliah, former Chief Minister David Marshall, and educator Francis Thomas.46

Members of the newly formed Presidential Council, including (front row, from left) Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, Minister for ForeignAffairs and Labour S. Rajaratnam, former Chief Minister David Marshall, educator Francis Thomas, President of Muslim Religious Council Haji Ismail bin Abdul Aziz, and Attorney-General Tan Boon Teik, waiting to take their oath of office at the Istana, 2 May 1970.

Yusof Ishak Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Wee Commission

While not all of the Commission’s proposals were ultimately incorporated into the final Constitution, the consultation process itself was deeply meaningful. It provided a platform for minority communities to have a voice during a crucial moment in Singapore’s history, and helped foster a shared sense of ownership over the nation’s future. Studies show that it is ultimately the act of participation that is most important for it can “engender public support for a constitution regardless of the extent to which it has an impact on the constitutional text and that the appearance of a fair process is the link between participation and legitimacy”.47

The Commission’s recommendations reflected careful design choices that continue to reverberate in Singapore’s constitutional approach. In avoiding entrenching a system with built-in special legal entitlements for minority groups, it constructed a constitutional order that emphasised equal citizenship, freedom of religion, political engagement, and inclusive policies over permanent legal distinctions and adversarial rights. It was a model that balanced difference and commonality, protection and equality—and in doing so, laid the foundation for a resilient and inclusive multicultural Singapore.

President Yusof Ishak being presented with a copy of the Wee Commission’s report, 27 August 1966.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

NOTES

-

Memorandum Setting Out Heads of Agreement for a Merger Between the Federation of Malaya and Singapore, 1961, Cmd. 33.

-

Albert Lau, A Moment of Anguish: Singapore in Malaysia and the Politics of Disengagement (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1998), 101.

-

Lee Kuan Yew, “Transcript of a Press Conference Given by the Prime Minister of Singapore, Mr. Lee Kuan Yew, at Broadcasting House” (speech, Singapore, 9 August 1965), National Archives of Singapore, lky19650809b.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 24, Sitting No. 9, Col. 429, 22 December 1965.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 19, Col. 1359, 16 March 1967.

-

Kevin YL Tan, “The Legal and Institutional Framework and Issues of Multiculturalism in Singapore”, in Beyond Rituals and Riots: Ethnic Pluralism and Social Cohesion in Singapore, edited by Lai Ah Eng (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2004), 100-102.

-

Tan, “The Legal and Institutional Framework and Issues of Multiculturalism in Singapore”, 102-104.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 14, Col. 1051- 1052, 21 December 1966.

-

Wee Chong Jin, “The First Local Chief Justice”, interview by Elisabeth Eber-Chan, November 1994, in Speaking Truth to Power: Singapore’s Pioneer Public Servants, edited by Loke Hoe Yeong (Singapore: World Scientific, 2019), 26-27.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 14, Col. 1051, 21 December 1966; Report of the Constitutional Commission 1966, 1966, Cmd. 29.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 18, Col. 1291, 15 March 1967.

-

Graham Starforth Hill, interview by Singapore Academy of Law, Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, Accession No. E000054, Reel 6, 19 September 2011.

-

“Minority Rights: A Call for Memos”, The Straits Times, 14 January 1966, 6; “Constitutional Commission, 1966”, The Straits Times, 16 January 1966, 13; “Surohanjaya Perlembagaan, 1966”, Berita Harian, 16 January 1966, 10.

-

For a list of names of individuals and organisations who submitted memoranda, see Appendix I in Report of the Constitutional Commission 1966, 1966, Cmd. 29.

-

“Problem of Another Man’s Sabbath”, The Straits Times, 15 March 1966, 7.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 19, Col. 1346, 16 March 1967.

-

“Indians to Draw Up Safeguards”, The Straits Times, 31 January 1966, 56.

-

“Indians Ask for Seven Basic Rights S’pore Charter”, The Straits Times, 3 March 1966, 5.

-

“Indians Ask for Seven Basic Rights in S’pore Charter”.

-

“How Other Races Can Also be Malays: Umno”, The Straits Times, 4 March 1966, 5.

-

“How Other Races Can Also be Malays”; “Privileges Not For Ever, Says Umno Chairman”, The Straits Times, 11 March 1966, 11.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 19, Col. 1333, 16 March 1967.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 19, Col. 1337, 16 March 1967.

-

“Minority Groups Seek Safeguards”, The Straits Budget, 9 March 1966, 10.

-

“Badan2 Melayu S’pura tidak mahu kaum-nya jadi puak ‘minoriti’”, Berita Harian, 17 June 1966, 2.

-

“How Other Races Can Also be Malays”.

-

“Privileges Not For Ever, Says Umno Chairman”. At least one person objected to this proposal to include a definition of Malay in the Constitution during oral representations, noting that being Malay and practising Malay customs does not equate to being a Muslim; see “The Right to Choose One’s Religion — By a Padre”, The Straits Times, 9 March 1966, 6.

-

“The Right to Choose One’s Religion”.

-

“The Right to Choose One’s Religion”. Another group that spoke up on religious freedom was the Singapore Hindu Sabai.

-

Kevin YL Tan and Thio Li-ann, Singapore: 50 Constitutional Moments that Defined a Nation (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2015), 52.

-

This was specifically proposed by UMNO and the Tamilian Association; see “Umno Wants Test in N-language for Citizenship Rule”, The Straits Times, 5 March 1966, 14, and “Minority Groups Seek Safeguards”.

-

“Problem of Another Man’s Sabbath”.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 18, Col. 1278, 15 March 1967.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 14, Col. 1051, 1058, 21 December 1966. Member of Parliament Suradi noted that the Report was “a very significant document in the annals of Singapore” particularly since even the presence of the UMNO Secretary-General did not preclude a unanimous report; see Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 19, Col. 1329, 1395, 16 March 1967.

-

See paragraph 11 in “Report of the Constitutional Commission 1966”, in Kevin YL Tan and Thio Li-ann, Constitutional Law in Malaysia & Singapore, 2nd ed. (Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong: Butterworths, 1997), 1021. See especially Articles 12 and 16

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 19, Col. 1370, 16 March 1967.

-

See paragraph 78 in “Report of the Constitutional Commission 1966”, in Tan and Thio, Constitutional Law, 1033.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 20, Col. 1396, 17 March 1967.

-

See “Report of the Constitutional Commission 1966”, in Tan and Thio, Constitutional Law, 1024-1025.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 20, Col. 1403, 17 March 1967.

-

Jaclyn Neo, “The Constitution and the Protection of Minorities: A Judicious Balance?”, in Evolution of a Revolution: Forty Years of the Singapore Constitution, edited by Thio Li-ann and Kevin YL Tan (London and New York: Routledge- Cavendish, 2008), 234-259.

-

Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (2020 rev. ed.) Article 39.

-

Tan and Thio, Singapore: 50 Constitutional Moments, 55.

-

Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (2020 rev. ed.) Article 68.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 20, Col. 1407, 17 March 1967.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 29, Sitting No. 2, Col. 61, 12 June 1969. See also paragraph 16 in “Report of the Constitutional Commission 1966”, in Tan and Thio, Constitutional Law, 1021-1022.

-

Ran Hirschl and Alexander Hudson, “A Fair Process Matters: The Relationship between Public Participation and Constitutional Legitimacy”, Law & Social Inquiry 49, no. 4 (2024): 2074.

***

Jaclyn Neo is Associate Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore.

***

This article is featured in the Founders’ Memorial’s +65 publication, Volume 4 — the flagship publication that aims to build thought leadership on Singapore’s independence and post-independence history and society. This issue explores multiculturalism, offering broader context on its origins and evolution in independent and post-independent Singapore (1950s–1970s). Limited copies are available at the Not Mere Spectators: The Makings of Multicultural Singapore exhibition. Download your online copy here.