Not Mere Spectators > Article - Navigating Diversity and Inclusion: Experiences of Singapore's Pioneer Malay Leaders, 1950s-1970s

Navigating Diversity and Inclusion:

Experiences of Singapore’s Pioneer Malay Leaders, 1950s–1970s

Sarina Anwar

Othman Wok (extreme right) and Haji Ya’acob Mohamed (extreme left) distributing foodstuffs to Southern Islanders to mark the start of fasting month, 8 December 1966.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Election campaign posters smeared with excrement. Accusations of being a “kafir” (infidel) and “pembelot” (traitor) to the Malay community. Even death threats.1 These were the vicious hostilities faced by early Malay leaders who chose broad-based representation over communal interests as Singapore moved towards merger with Malaya and eventual independence. What drove their convictions and how did these shape their experiences as leaders in a diverse, multiracial society?

A Racialised Political Landscape (1950s–Early 1960s)

The years leading up to Singapore’s independence in 1965 were fraught with racial tensions. Colonial rule had left deep socioeconomic inequalities between races. In 1950, Singapore experienced a harrowing instance of unrest that exposed deep- seated racial and religious fault lines—the Maria Hertogh riots catalysed by the custody battle between Maria’s adoptive Malay family and her Eurasian parents. Events such as these deepened racial fractures and entrenched the perception that race was a volatile issue.2 In this charged atmosphere, navigating racial diversity proved complex.

In the decades after World War II, Singapore United Malays National Organisation (Singapore UMNO, or simply SUMNO) had positioned itself as the champion of Malay minority rights and interests, becoming the default political party for many Malays.3 Originally an extension of UMNO Johore, SUMNO established its independent operations in Singapore in 1954. Nonetheless, it remained ideologically aligned with its parent organisation. Central to this alignment was the concept of Tanah Melayu (Land of the Malays). While this vision had emerged in Malaya’s anti-colonial struggle calling for the return of land to Malays, it took on a different character in Singapore where Malays comprised 13% of the population.4 Here, SUMNO adapted its original mandate into one of protecting Malay rights from perceived oppression by a non-Malay majority.

With the expansion of the franchise and the introduction of competitive electoral politics following the promulgation of the Rendel Constitution in 1955, SUMNO’s reach and influence grew. From 1955 to 1959, SUMNO flexed its political muscle in Malay- majority areas, namely the Southern Islands, Geylang Serai, and Kampong Kembangan. As former SUMNO member Rahmat Kenap succinctly described the political landscape of the period, “orang Melayu waktu itu menganggap UMNO itu Melayu. Melayu itu UMNO” (the Malays at that time believed that UMNO is Malay. Malay is UMNO).5

Beyond Communal Politics

SUMNO’s communal mission was, however, at odds with the lived experience of Malays who interacted daily with different races. In fact, many Malays in Singapore comfortably straddled different cultures, having been exposed to them from a young age. Nowhere is this as evident as in the life story of Othman Wok, who would eventually become Minister for Social Affairs in 1963. Growing up in pre-World War II Singapore, Othman Wok was educated in English-medium schools, at a time when these institutions were viewed suspiciously by many Malays as seeking to convert Muslims to Christianity. Indeed, it was at Raffles Institution that he rubbed shoulders with students of different races, including future Minister for Law E. W. Barker. When the People’s Action Party (PAP) was formed in 1954, he joined within days, drawn to its vision of racial equality. For Othman Wok, SUMNO’s Malay-centric politics held little appeal compared to the promise of a truly multiracial Singapore.6

Othman Wok’s path was followed by another Raffles Institution alumnus: the future Minister of State for Education and Foreign Affairs Rahim Ishak. In 1959, Rahim joined the PAP after meeting Lee Kuan Yew through his brother Yusof Ishak (who would later become the first Malayan-born Head of State and Singapore’s first President). Described as a “bookish person” with an interest in socialism, Rahim was attracted to PAP’s manifesto of equality.7 He envisioned a future where Malays could maintain their identity while thriving in Singapore’s “modern, multiracial, multicultural, secular community”, free from outdated ways of thinking and able to compete on equal footing with the rest of the population.8 Like Othman Wok, he believed that true protection for minorities lay not in communal politics but in building a genuinely multiracial society where all communities could progress together.9

Crowds awaiting the arrival of Tunku Abdul Rahman to open UMNO House at Changi Road, 14 February 1965.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Progress for All

Away from the political limelight, trade union leaders from Singapore’s largely working-class Malay community also embraced this vision of progress for all and of class solidarity regardless of race. UMNO’s priorities in Malaya in reinstating the Malay monarchy had little relevance to the daily struggles of the Malay working class in Singapore. SUMNO leaders also did little to address the practical, on-the- ground needs of Singapore’s Malays. As trade unionist and PAP founding member Mofradi Haji Mohamed Noor recalled, when Singapore General Hospital workers needed legal support in 1953, it was non-Malay lawyers Lee Kuan Yew and Kenneth Michael Byrne who stepped forward, and not SUMNO leaders.10

Rahmat Kenap, originally a trade unionist in SUMNO, was particularly disappointed when SUMNO leader Abdul Hamid Jumat actively declined his requests for assistance during the 1957 Singapore Telephone Board Workers’ Union strike.11

In 1957, he quit SUMNO before joining the PAP two years later. His motivations for joining the latter, however, went beyond mere frustration with SUMNO leadership. He recognised that Singapore’s demographic reality—80% Chinese and roughly 6% Eurasian and Indian—meant that effective political representation needed to transcend communal interests. Significantly, he emphasised how the PAP leadership “berjiwa kaum buruh” (held a pro-worker stance).12 In Rahmat Kenap’s political calculations, the PAP offered a more promising path for advancing workers’ rights for all, including the Malays.

Rahim Ishak (second from left) being sworn in as a Member of the Legislative Assembly, with his brother Yang di-Pertuan Negara Yusof Ishak (second from right) and Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (extreme left) witnessing, 19 October 1963.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

|

Malay Trade Union Leaders The bulk of the PAP’s early pre- independence Malay leaders were trade union leaders. They included Baharuddin Mohamed Ariff and Ahmad Ibrahim, both of whom were very popular across racial lines. During the 1959 Legislative Assembly General Elections, Baharuddin won the seat of Anson. Ahmad was nominated by his union to contest in Sembawang, winning as an independent candidate before openly aligning with the PAP.13 He would subsequently serve as Minister for Health (1959–1961) and Minister for Labour (1961–1962). Other trade unionists include Othman Wok, Ariff Suradi, Mahmud Awang, Rahmat Kenap, and Ismail Rahim.

Rahmat Kenap, Ariff Suradi, and Haji Ya’acob Mohamed (clockwise from top) in a Berita Harian article featuring the roles of Malay political leaders in Singapore’s road to independence, 18 July 1988. Berita Harian © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction. |

A Test of Resolve

Rahmat Kenap’s defection was part of a larger exodus from SUMNO to the PAP in 1959, the year in which Singapore gained full internal self-government. Led by the charismatic Haji Ya’acob Mohamed, 31 SUMNO leaders made the switch overnight early in that year, prompted in large part by UMNO Kuala Lumpur’s refusal to focus on Singapore’s independence.14 The defectors—including influential figures Buang Omar Junid, Ariff Suradi, and Sahorah Ahmat—joined their multiracial PAP colleagues to contest in the 1959 General Elections. The Malay leaders helped the PAP to win the Malay ground, resulting in sweeping victories across the country, with the PAP winning 43 out of 51 seats in the Legislative Assembly. This signalled a new direction for Malay political leadership in a diverse and multiracial city-state.

While electorally significant, the PAP’s hold of the Malay ground in the wake of the 1959 elections nevertheless remained tenuous and hotly contested. The dust had barely settled before issues pertaining to land, citizenship, and the Malay language were stirred up against the backdrop of sensitive negotiations between the Singapore and Federal governments over Merger.15 With the 1963 General Elections looming ahead, UMNO doubled down on their resistance against the PAP and aggressively fought to tighten their influence over Singapore’s Malay community.

Branded as traitors to their community, the Malay PAP leaders faced constant derision for joining what critics had mockingly called “Party Anak Peking” (child of Beijing) before the pro-Communist Chinese elements splintered from the party in 1961.16 Even a songkok offered little protection; Rahmat Kenap, often seen wearing this traditional Malay headpiece, found himself labelled as “Chinese” by some Malays.17

For Othman Wok, the 1963 elections were the ultimate test of his courage and determination. Earlier, in 1959, he had already endured taunts and provocations while mounting his debut electoral campaign in the Kampong Kembangan ward:

“Pergi balik kampunglah!

(Go back to your village!)

Apa ini masuk China punya parti! Ingat boleh menangkah? Ini UMNO punya tempat.

(Why did you join a Chinese party? Do you think you can win? This is UMNO’s territory.)”18

His biography recounts the looming threat of violence which he stared down unflinchingly:

“They took my leaflets and threw them away right in front of me. I just walked.

I didn’t care... Some of my posters were smeared with human excreta. But that did not dampen my spirit when I was walking alone distributing leaflets all over Kampong Melayu, Kampong Batak, and Kampong Kembangan, even though I was scared that I might be hammered.”19

The brewing atmosphere of hostility ultimately reached its peak during the July 1964 racial riots, when UMNO systematically worked to turn the Malay community against PAP’s Malay leaders, particularly targeting Othman Wok and founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. This was in spite of the PAP already securing decisive victories in the September 1963 elections, winning in the UMNO strongholds of the Southern Islands, Geylang Serai, and Kampong Kembangan. Dissatisfied by their inability to win over Singapore Malays, UMNO leaders turned to inflammatory rhetoric. During one particularly fiery speech at Othman Wok’s constituency of Pasir Panjang on 12 July 1964, UMNO leader Syed Jaafar Albar whipped the crowd into a frenzy by declaring, in no uncertain terms: “We finish them off… kill him, kill him. Othman Wok and Lee Kuan Yew.”20 Barely two weeks later, race riots broke out on 21 July between Malays and Chinese.

Voters casting their ballots in the 1959 General Elections, 30 May 1959.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

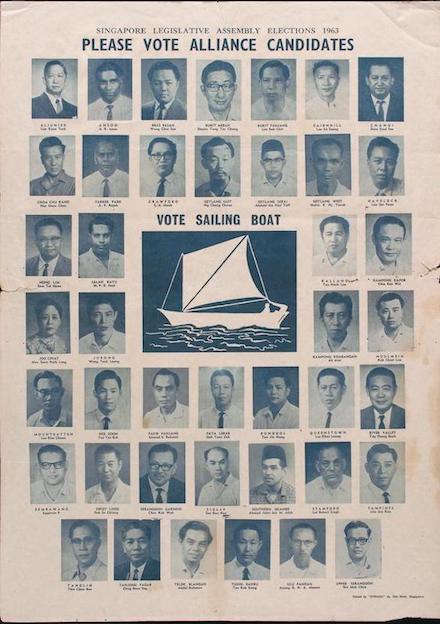

Singapore Alliance’s poster for the Singapore General Elections, 1963. SUMNO was a constituent member of the Singapore Alliance.

Collection of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Syed Jaafar Albar speaking at a mass rally at SUMNO’s Kampong Ubi branch, 27 September 1963.

The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Undaunted, the leaders stood firm, working closely with communities of different races through the Jawatankuasa Muhibbah (Goodwill Committees). Together, they toured troubled areas to speak with community leaders and residents to appeal for calm and to rebuild trust.21 This resolve, in turn, earned the leaders high praise from Lee Kuan Yew. In a speech at his 75th birthday dinner in 1998, Lee paid tribute to them:

“Othman, I remember your staunch support and loyalty during those troubled days when we were in Malaysia and the tensions were most severe immediately before and following the bloody riots in July 1964... Because of the courage and leadership you showed, not a single Malay PAP leader wavered (in 1965)... That made the difference to Singapore.”22

Othman Wok with Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew during a tour to restore peace and instil confidence during the racial riots, 1964.

The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

|

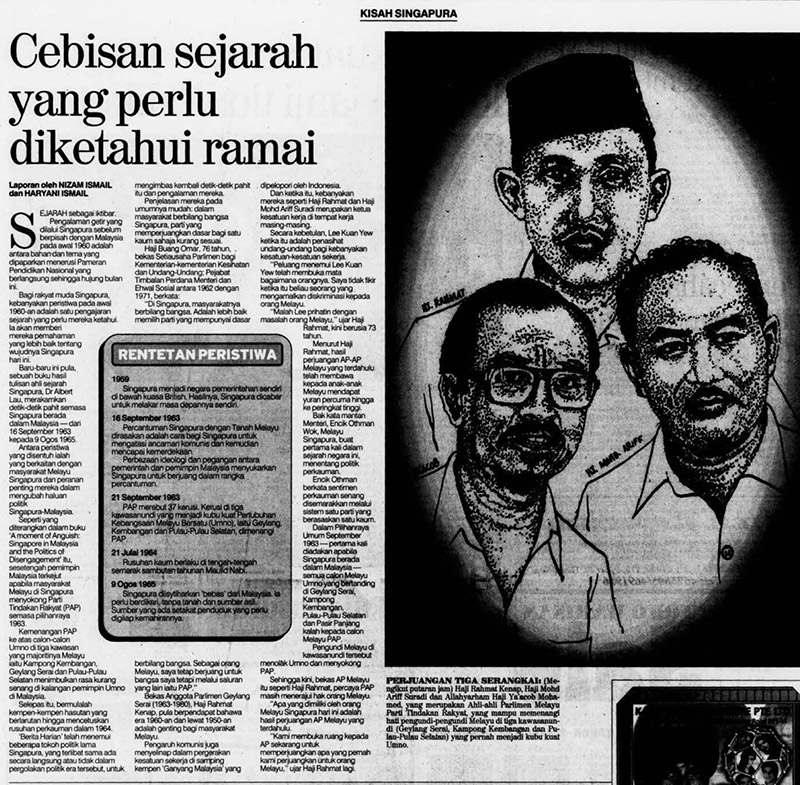

Seen and Heard in Not Mere Spectators: The Makings of Multicultural Singapore 1964 Racial Riots Singapore merged with Malaya, Sabah, and Sarawak to form Malaysia on 16 September 1963. Beneath this political union, racial tensions simmered, manifesting in heated exchanges between Singapore’s ruling People’s Action Party and the United Malays National Organisation on Malay rights and community issues. All this came to a boiling point in July 1964. At a procession to celebrate the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday on 21 July, clashes erupted between Malay participants and Chinese bystanders. It escalated into riots across the island. When the curfew was finally lifted on 7 August, 23 people had died and 454 others were injured. During the riots, shields like the one below were a frequent sight on the streets. They were part of policemen’s riot gear, used to maintain order as violence spread.

Police shield, 1960s. Gift of Police Headquarters. Collection of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Staff attending to victims of the racial riots at Singapore General Hospital, 23 July 1964. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. |

Separation and Beyond... The Work Continues

When Singapore separated from Malaysia in 1965, each Singapore Malay leader responded differently, but they remained united in their convictions of a truly multiracial Singapore where all communities could progress together. On one hand, Lee Kuan Yew had called aside then-Minister for Social Affairs Othman Wok, concerned that the separation might affect him as a Malay.23 Othman Wok, exhausted by two years of racial tensions and the resultant riots, and threats on his life, signed the Separation Agreement without hesitation. “Separation to me meant less pressure. As a Malay PAP Minister, I had been in a difficult position. With the separation, I thought that it would be much easier for me and everyone else to get on with the job,” he would later muse.24 Meanwhile, Mahmud Awang, true to his trade union roots, worried about how workers would fare in Singapore’s smaller economy. This came at a real personal cost to him—relatives across the Causeway now viewed him as “a foreigner”.25

Haji Ya’acob was deeply disappointed over the separation, but looked towards the future. He would later reflect with poignancy in a 1987 interview with the National Archives of Singapore:

“Nasi dah jadi bubur. Terpaksalah bubur tu saya olahkan. Masukkan sikit santan kelapa, gula, kacau jadikan dodol, wajik dan apalah supaya tak terbiar begitu saja. Inilah tugas saya.”26

“The rice has turned into porridge. I had no choice but to work with this porridge. Add some coconut milk, sugar, stir it to make dodol, wajik, and whatever else, so that it would not go to waste. This was my duty.”

Mahmud Awang (top) and Ariff Suradi (bottom) in their People’s Defence Force uniforms, 19 March 1966.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Making the best of changed circumstances, Haji Ya’acob focused on his responsibilities to “help advance the Malay community in all fields”.27 In Parliament on 15 December 1965, he delivered a speech that would be broadcast three times on the radio at Lee Kuan Yew’s request. This was in response to Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman’s invitation to Singapore Malays to migrate to Malaysia, with offers of land parcels as a form of enticement. Haji Ya’acob spoke firmly to assert Malays’ rightful place in Singapore: “We Malays have never migrated. I consider that the spirit of migration is a cowardly spirit. The various races must live in peace and understanding.”28 For him, separation represented the beginnings of Singapore as an independent, sovereign, and multiracial nation-state where Malays belonged, while also emphasising that any problems faced by Malays needed to be resolved as national issues.

To be sure, independent Singapore’s Malay leaders walked a fine line between safeguarding Malay rights and promoting multiracialism. In 1966, leaders like Othman Wok worked alongside civil servants and community figures such as Attorney-General Ahmad Ibrahim to get the Administration of Muslim Law Act (AMLA) passed in Parliament. AMLA provides a centralised administration of Muslim life in Singapore, while fitting within Singapore’s broader legal system.29

***

Beyond the political leadership, we also had community leadership. People like the late Ridzwan Dzafir, Yusof Ahmad, and Yatim Dohon were known for their penchant for working together with the Malay community to build a community of excellence and strength.30

Former Senior Parliamentary Secretary for Information and the Arts Yatiman Yusof in an interview with the Founders’ Memorial, 2022

***

Haji Ya’acob exemplified this delicate approach to minority rights. While he had advocated for the special position of Malays in Singapore to be recognised in the Constitution, and the Constitution did indeed recognise “the special position of the Malays, who are the indigenous people of Singapore”, Haji Ya’acob had opposed similar positions for Malays in Malaya.31 As he later explained when recounting his experiences in post-independence Singapore, “I help the Malays not because they are Malays, but because they are a community who is the least advanced in Singapore.”32

State Advocate-General (later Attorney-General) Ahmad Ibrahim inspecting the 26th Gan Eng Seng scout group during the opening of the school’s annual exhibition, 1964.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Notably, these leaders also played a crucial role in shaping Malay values to align with larger national ones, urging Malays to progress alongside other races. They were not afraid to question issues within their own community. Rahmat Kenap, for example, called out untrustworthy haj (pilgrimage) leaders in Singapore, encouraging them to improve their practices. Even before Independence, Haji Ya’acob had supported the establishment of Sang Nila Utama Secondary School in 1961, Singapore’s first Malay-medium secondary school which attracted students from around the region to its curriculum focusing on mathematics and science. True to his commitment to forging a progressive Malay community, in the 1970s, he railed against “amalan-amalan karut” (superstitious practices) and challenged anti-science attitudes espoused by some Islamic scholars.33

|

Read more about Article 152 of the Singapore Constitution, on minorities and the special position of Malays, on page 78 of the +65 journal, Volume 4. |

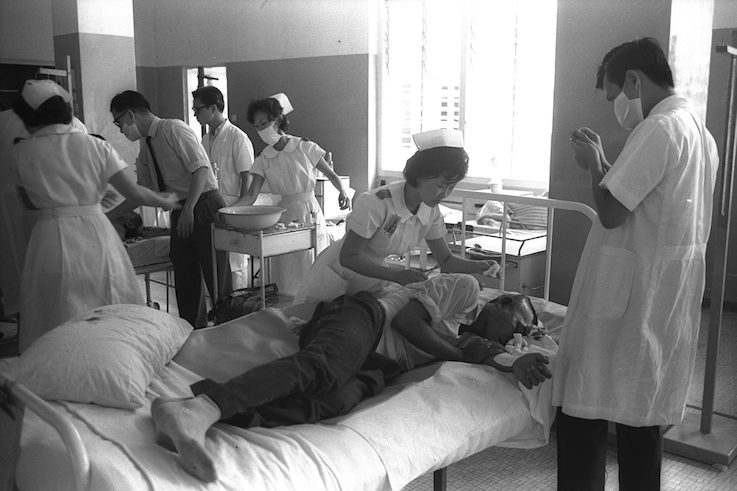

Member of Parliament for Geylang Serai, Rahmat Kenap, giving a speech at a Goodwill Committee meeting with his trademark songkok, 1960s.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

|

Haji Ya’acob Mohamed, A Voice for Justice and Equality Among the pioneer batch of Malay leaders, Haji Ya’acob stands out for his political acumen and unwavering commitment to justice and equality. A powerful orator, he won in the Chinese-majority constituency of Bukit Timah in 1959 before clinching the SUMNO stronghold of the Southern Islands in 1963. Known for his fierce criticism of opponents and willingness to question his own allies, Ya’acob embodied the spirit of democratic leadership. He stated, “Every citizen in a country which practises a democratic system has the right to criticise government policies if a mistake has been made or to give constructive views.”34 After Independence, Ya’acob held several political offices, eventually rising to the position of Senior Minister of State in the Prime Minister’s Office. He stepped down from Parliament in 1980.

Haji Ya’acob delivering a speech at Ulu Pandan, 11 September 1963. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. |

Conclusion

“Beralah bukan mengalah. Beralah untuk hidup sama-sama dalam masyarakat ini, kita sudah terima. Tetapi harus ada keadilan.”35

“To compromise is not to give in. To compromise in order to live together in this society, we have accepted that. But there must be justice.”

Haji Ya’acob Mohamed, in a 1986 interview with the National Archives of Singapore

Singapore’s Malay leaders rose to the occasion at a time when the fate of our nation hung in the balance. They proved their mettle in a nascent democracy, balancing communal interests with larger national ones, with each equally committed to the ideal of a Singapore for all, “regardless of race, language or religion”.36

Their legacy extends beyond their era. As Singapore continues to evolve, the beliefs and principles these leaders fought for—such as how Malays could maintain their identity while thriving in Singapore’s multiracial society—remain relevant. The journey of these Malay leaders in the 1950s to 1970s shaped Singapore’s path to becoming a multiracial nation and continues to inform conversations about navigating diversity and inclusion in contemporary society.

Othman Wok reflecting on his political career, 2017.

The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

|

Sahorah Ahmat, the First Elected Female Malay Assemblywoman

Sahorah Ahmat broke ground as not just a Malay leader but also a woman in politics. She is most remembered for her dramatic entry into the Legislative Assembly chamber. Gravely ill, she was carried in on a stretcher to cast the decisive vote in the 1961 motion of confidence which saved the PAP government from pro- communist elements. It was not out of political loyalty, but from her faith in her Chinese colleague Chan Chee Seng—a testament to the cross-racial bond between them.37 Yet her legacy runs deeper. A champion of women’s rights, she advocated stronger protections for Muslim women within Islamic law.38

Nearly four decades would pass before another Malay woman, Halimah Yacob, was elected into Parliament.39

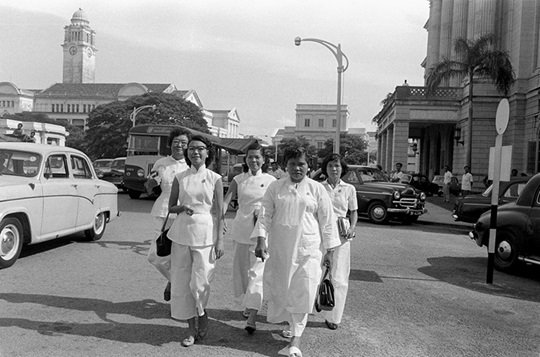

Sahorah Ahmat (front, right) with fellow Assemblywomen Chan Choy Siong (front, left) and Hoe Puay Choo (back, centre), 5 June 1959. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

|

NOTES

-

“Eulogy by PM Lee Hsien Loong at Memorial Service of the late Othman Wok”, Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, 19 April 2017, https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/eulogy-pm-lee-hsien-loong-memorial-service-late-othman-wok (accessed 11 August 2025); Sonny Yap, Richard Lim, and Leong Weng Kam, “Malay Heroes Who Changed History”, in Men in White: The Untold Story of Singapore’s Ruling Political Party (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 2010), 284.

-

See Norman Vasu and Juhi Ahuja, Singapore Chronicles: Multiracialism (Singapore: Straits Time Press, 2018).

-

SUMNO served as the Singapore branch of UMNO. Founded in 1946 by Malay nationalist Dato’ Onn Jaafar, UMNO championed Malaya as a “Malay country to be ruled by Malay leaders”. After Singapore’s Independence, SUMNO was officially renamed Pertubuhan Kebangsaan Melayu Singapura (PKMS) in 1967. See “UMNO History”, UMNO Malaysia, https://umno.org.my/language/ en/sejarah/ (accessed 11 August 2025); “Singapore Malay National Organisation is Formed”, Singapore Infopedia (National Library Board), https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=183c4002-a13d-4e58-9219-1a7bccd0ac41 (accessed 11 August 2025).

-

S. C. Chua, “Report on the Census of Population 1957”, Papers Presented to Parliament, Cmd. 19

of 1964, 4 August 1964, https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/government_records/record-details/fbe1162a-0b80-11e8-a2a9-001a4a5ba61b (accessed 12 August 2025). -

Rahmat Kenap, interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, Accession No. 000121, Reel 10, 16 December 1981.

-

Zuraidah Ibrahim, “The Malay Mobilisers: Ahmad Ibrahim, Othman Wok, Yaacob Mohamed & Rahim Ishak”, in Lee’s Lieutenants: Singapore’s Old Guard, edited by Kevin YL Tan and Lam Peng Er (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 2018), 215-216.

-

Zuraidah, “The Malay Mobilisers”, 227.

-

“Malays Will be Malays: Pledge by Rahim Ishak”, The Straits Times, 12 February 1967, 7.

-

Zuraidah, “The Malay Mobilisers”, 228.

-

Yap, Lim, and Leong, “Malay Heroes Who Changed History”, 286.

-

Rahmat Kenap, interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, Accession No. 000121, Reel 6, 27 October 1981; “STB Strike: Jumat to Step In?”, Singapore Standard, 11 July 1957, 3.

-

Rahmat, interview, Reel 6; “STB Strike”.

-

“1959 Legislative Assembly General Election Results”, Elections Department Singapore, https://www.eld.gov.sg/elections_past_parliamentary1959.html (accessed 11 August 2025).

-

Zuraidah, “The Malay Mobilisers”, 223.

-

“Pendudok-pendudok enggan turut perentah keluar”, Berita Harian, 14 April 1963, 1.

-

Yap, Lim, and Leong, “Malay Heroes Who Changed History”, 284; Zuraidah, “The Malay Mobilisers”, 216.

-

Rahmat, interview, Reel 6.

-

Othman Wok, Never in My Wildest Dreams (Singapore: Raffles, 2000), 128.

-

Othman, Never in My Wildest Dreams, 128.

-

Cheong Suk-Wai, “Remembering Othman Wok: A Champion of Multi-Culturalism”, The Straits Times, 18 April 2017, https://www. straitstimes.com/singapore/ remembering-othman-wok-a- champion-of-multi-culturalism (accessed 14 August 2025).

-

“Calls for Goodwill, Harmony by Union Bodies”, The Straits Times, 28 July 1964, 4.

-

“Eulogy by PM Lee Hsien Loong at Memorial Service of the late Othman Wok”.

-

Zuraidah, “The Malay Mobilisers”, 219.

-

Othman, Never in My Wildest Dreams, 186.

-

Mahmud Awang, “Mahmud Awang: The Trade Union Leader”, in We Also Served: Reflections of Singapore’s Former PAP MPs, edited by Chiang Hai Ding and Rohan Kamis (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 2014), 67.

-

Ya’acob bin Mohamed, interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, Accession No. 000747, Reel 18, 7 January 1987.

-

Ya’acob, interview, Reel 18.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 24, Sitting No. 4, Col. 177, 15 December 1965.

-

“Administration of Muslim Law Act 1966”, Singapore Infopedia (National Library Board), https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=c5f54cb7-86c4-4e0a-a518-3e2bd8e234ad (accessed 26 August 2025).

-

Yatiman Yusof, interview by Founders’ Memorial, 28 February 2022.

-

Kevin Y. L. Tan, “The Legal and Institutional Framework and Issues of Multiculturalism in Singapore”, in Beyond Rituals and Riots: Ethnic Pluralism and Social Cohesion in Singapore, edited by Lai Ah Eng (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2004), 102-104.

-

Sulaiman Jeem and Abdul Ghani Hamid, Ya’acob Mohamed (dalam API, PKMM, UMNO, PAP) (Singapore: Penerbitan Wisma, 1990), 135.

-

“Amalan-amalan karut tak dapat bantu mencapai”, Berita Harian, 31 August 1974, 2; “Para ulamak perlu ubah sikap dan ikut arus kemajuan”, Berita Harian, 11 July 1975, 4.

-

“Haji Ya’acob Agrees Raja’s Words Were Ill-Chosen”, The Straits Times, 14 December 1986, 2.

-

Ya’acob bin Mohamed, interview by Mohd Yussoff Ahmad, Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, Accession No. 000747, Reel 3, 15 November 1986.

-

Singapore National Pledge.

-

37 Chan Chee Seng, interview by Audrey Lee-Koh Mei Chen, Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, Accession No. 003320, Reel 7, 26 August 1980.

-

Suhail Yazid, “A Malay Woman in the House: Recovering Sahorah Ahmat’s Legacy in Singapore’s History”, in Beyond Bicentennial: Perspectives on Malays, edited by Norshahril Saat, Wan Hussin Zoohri, and Zainul Abidin Rasheed (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2020), 613-637.

-

“Halimah Yacob: First Woman President of Singapore”, Singapore Women’s Hall of Fame, https://www.swhf.sg/profiles/halimah-yacob/ (accessed 10 August 2025).

***

Sarina Anwar is a former History teacher turned Assistant Curator at the Founders’ Memorial. Still teaching—just in different ways.

***

This article is featured in the Founders’ Memorial’s +65 publication, Volume 4 — the flagship publication that aims to build thought leadership on Singapore’s independence and post-independence history and society. This issue explores multiculturalism, offering broader context on its origins and evolution in independent and post-independent Singapore (1950s–1970s). Limited copies are available at the Not Mere Spectators: The Makings of Multicultural Singapore exhibition. Download your online copy here.