Not Mere Spectators > Article - Perspectives on Religious Harmony in Singapore: Origins and Evolution

Perspectives on Religious Harmony in Singapore:

Origins and Evolution

Sharifah Afra Alatas

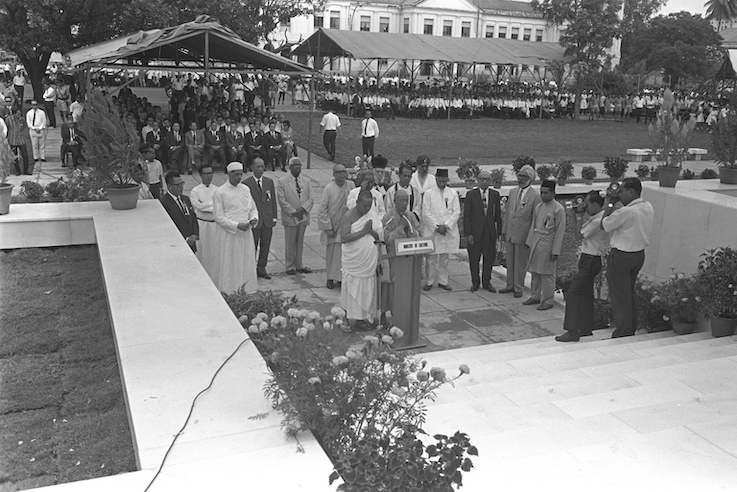

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (middle) meeting with IRO council members, 30 September 1965. Permanent Secretary in the Prime Minister’s Office Stanley Stewart (standing in background) and Attorney-General Ahmad Ibrahim (right, in black jacket) are seen in this photograph as well.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

“Actually, I don’t see why we need to do this.” These were the words of a fellow undergraduate who had approached me for advice on designing an inter-religious dialogue session that his student society was planning to organise. As an active advocate of interfaith work, this comment has stayed with me despite having left university for several years. It has prompted me to reflect on why some may not understand, or see, the need for such conversations.

From my experience and observations, one reason may be that Singaporeans are more aware of the state’s role in fostering racial harmony, as compared to similar efforts where religious harmony is concerned. After all, racial harmony initiatives are at the forefront of our lived experiences. These include occasions such as Racial Harmony Day, and policies like the Ethnic Integration Policy which ensures a balanced mix of different ethnic communities in our Housing and Development Board (HDB) towns.

Although lesser-known, efforts to promote and maintain religious harmony have in fact existed in Singapore as early as our pre-independence years. This is significant given that no more than a third of Singapore’s population follows any one religion today, resulting in a diversity described by the Pew Research Centre as “remarkable on a global scale”.1 While policies and laws often take centre stage, civil society has played its own part, with the 1949 formation of the Inter-Religious Organisation (IRO) being one pivotal moment in this decades-long endeavour to foster peace, tolerance, and mutual understanding. How have both the government and society played complementary roles in the period leading up to and after Singapore’s independence? How has the nature of their efforts changed over the years?

The Formation of the Inter-Religious Organisation

Civil society efforts to promote religious harmony came to prominence in Singapore in the years following the end of World War II. This was a time of socio-political turbulence, when disagreements among different communities often spilled over into conflict.2 Conscious of the need to foster goodwill among religious leaders, the President of the All-Malaya Muslim Missionary Society (AMMS, known today as Jamiyah Singapore), Syed Ibrahim Alsagoff, invited 40 guests of varying religious affiliations to lunch in January 1949. The lunch was held in honour of Maulana Mohamed Abdul Aleem Siddiqui, an esteemed Muslim scholar and missionary from Pakistan who had earlier helped found the AMMS in 1932, but Sir Malcolm MacDonald, British Commissioner-General for Southeast Asia, was also among the guests present.3 According to a compilation of the IRO’s early speeches, The Contribution of Religion to Peace, it was at this lunch that the idea of forming a “board of religious leaders” was first broached.4

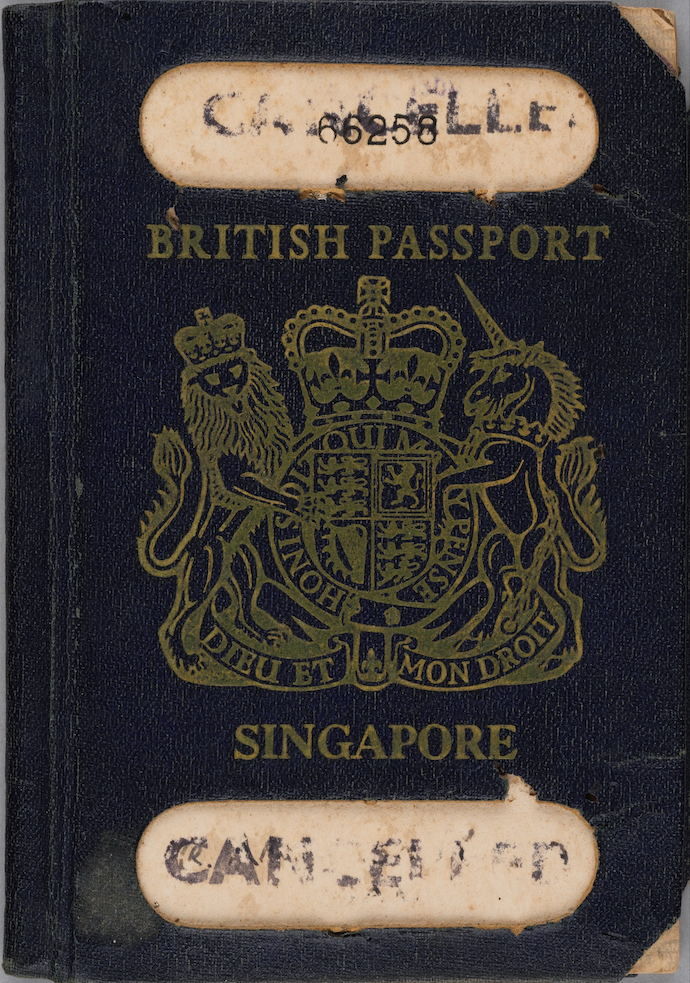

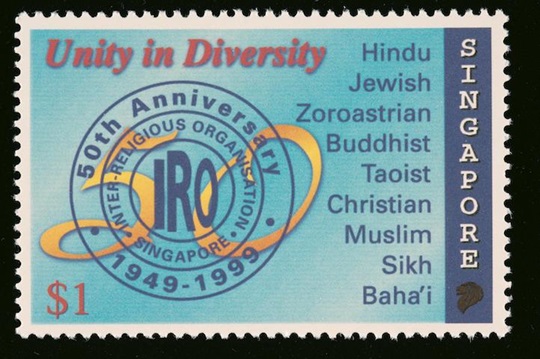

At a second meeting held on 4 February 1949, this idea began taking concrete shape. Here, the Maulana proposed the formation of an association comprising the leaders and laymen of all religions of Malaya.5 This organisation, he hoped, would “create a spirit of brotherhood” that could help “spread the moral virtues” of members’ religions.6 A further flurry of four meetings later, the Inter-Religious Organisation of Singapore and Johor Bahru was officially born, with a constitution that provided for six religions—Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, and Sikhism—to be represented among its founding members. Zoroastrianism was added to this list in 1961, followed by Taoism and the Baha’i faith in 1996, and Jainism in 2006.7

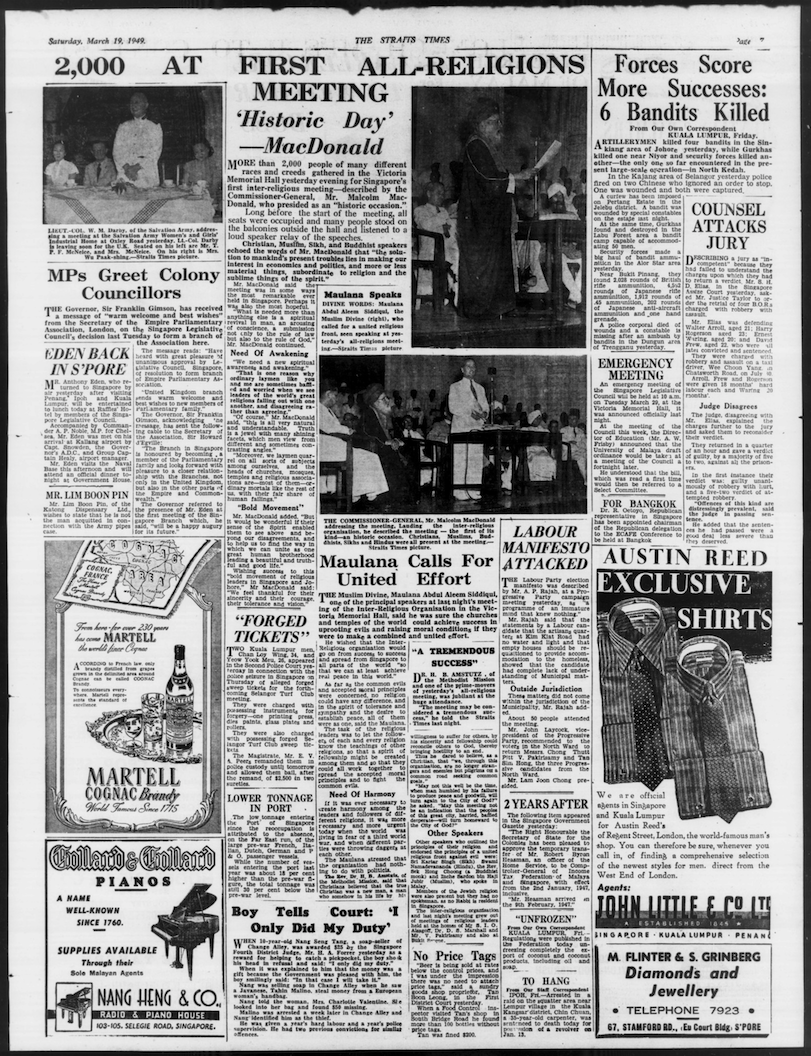

Two months after its constitution was promulgated, the IRO held its first public meeting at Victoria Memorial Hall on 18 March 1949, with a crowd of 2,000 people in attendance.8 In his opening remarks at the event, Commissioner-General MacDonald—now the IRO’s inaugural Patron—commended the “bold movement of religious leaders in Singapore and Johor”, and expressed gratitude for “their sincerity and their courage, their tolerance and vision”.9 This gesture was significant as it represented the colonial administration’s endorsement of the IRO’s grassroots effort, thus laying the ground for the government and society to forge closer partnerships in the future. Importantly, other speeches made during this meeting also clarified that inter-religious dialogue did not preclude one’s continued belief in one’s own faith.10 Rather, the IRO was meant to strengthen individual religious convictions—to “make men follow their religions strictly”—and was thus framed as encouraging a “spiritual revival” in the community.11

Postage stamp issued on the 50th anniversary of the IRO, 1999.

Collection of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A Straits Times report on the IRO’s first public meeting which took place a day earlier, 19 March 1949.

The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Emergent Years

Barely two years after its founding, the IRO found itself in the spotlight after riots broke out in Singapore on 11 December 1950. This crisis was triggered by a custody battle over a 13-year-old Dutch-Eurasian girl, Maria Hertogh, who had been raised as a Muslim by her Malay foster mother during the Japanese Occupation, but was subsequently returned to her Catholic birth parents by order of the courts. The case was highly publicised and became a flashpoint for violent clashes which left 18 dead and more than 170 injured.12

In the aftermath of the riots, the IRO issued a public statement on 11 January 1951 at Commissioner-General MacDonald’s request. Signed by council members of various religious affiliations, the statement read:

“We repudiate and condemn mob violence and political terror...We pledge ourselves and summon all people of goodwill to further the cause of men living in freedom and righteousness according to the Law of God; and to this end to advance and protect those lawful associations in which men grow to freedom and justice—the family, the school, the occupational association or union, the nation, the religious community.”13

Demonstrators protesting outside the Supreme Court during the Maria Hertogh riots, 11 December 1950.

Kenneth Chia Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

To some contemporary observers, the IRO’s statement—issued a month after the riots—was a case of too little and too late.14 However, when race riots broke out 14 years later in 1964, the IRO swung into action quickly, recording broadcasts to calm tensions in riot-stricken areas such as Geylang Serai.15 In a 1985 interview with the National Archives of Singapore, Mehervan Singh, a former Secretary of the IRO, recalled the dangers council members faced driving around Singapore to publicise the IRO’s statement:

“During [the] curfew, I drove in my car with the draft statement to St Andrew’s School. The statement was cut on a stencil and duplicated. The principal of the school was in our Council, Francis Thomas. He suggested [to Government officials at City Hall] that we be given labels for our cars. [However, I was sure that] somebody driving away in a car with the label [would invite] brickbats. So, all of us rejected labels for our cars.”16

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (centre of table) and Minister for Finance Dr Goh Keng Swee (right) meeting with IRO representatives at the height of the racial riots, 25 July 1964.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The issuance of statements aside, the early work of the IRO was at times marred by financial constraints, a lack of meeting spaces, and disagreements between council members.17 Even so, the IRO steadily but surely left its imprint on Singapore’s public landscape. For example, in the mid-1950s, the IRO proposed for all government schools to offer compulsory religious education.18 This would later lead to a 1960 collaboration with the Ministry of Education, which introduced a “Right Conduct” course in the primary school syllabus, based on ethics and religious knowledge.19 The IRO’s credibility also received a boost when its representatives were called upon by Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock to pronounce a benediction for the opening of the Merdeka Bridge and Nicoll Highway in 1956.20 This practice of having religious leaders grace national events with their blessings would subsequently become a common sight during occasions such as the installation of Singapore’s first Malayan-born Yang di-Pertuan Negara in December 1959, Singapore Armed Forces Training Institute commissioning ceremonies, and even early National Day celebrations.21 While symbolic, the prayers nevertheless serve as a visible reminder of the peace and harmony that exists among different religions in Singapore.

Entrance to Merdeka Bridge and Nicoll Highway, 1960s.

Collection of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Trusted Partner

By the time Singapore was thrust out of the Federation of Malaysia in August 1965, the IRO had become a trusted partner to a fledgling nation-state determined to treat all religions even- handedly. Its Council—referred to in government statements as the Inter-Religious Council—was often called upon by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew to help defuse tensions and mediate between opposing viewpoints. In one instance in September 1965, troublemakers attempted to stir up tensions between Christians and Muslims by alleging that some religious adherents had been proselytising in an inappropriate manner. Recognising the danger such “synthetic froth” could pose, Lee summoned the Council for a meeting. He emphasised the “multiracial, multilingual, multireligious” nature of Singapore society, and stated firmly that “tolerance between racial groups, linguistic groups and religious groups” was “of the essence for [Singapore’s] survival”.22 To assure Singaporeans of their commitment to this fundamental principle, IRO leaders then quickly responded with a statement condemning “unfair or unethical methods [...] in the propagation of religion”.23

In another anecdote related by Prime Minister Lee during the parliamentary debate on the 1966 Constitutional Commission Report, the Council’s mediation helped foster a compromise among different religious groups seeking to publicly broadcast their sermons or calls to worship. After a “sober but... trying exploration of compromise proposals”, all groups agreed to confine their loudspeakers and electronic aids to within their premises.24 This, Lee noted, sent a clear message that the government would approach such matters delicately and sensitively, and not favour any religious denominations above others.25

One further episode from the late 1960s showcased the IRO’s role as a neutral arbiter in situations involving complex religious sensitivities. In this instance, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce had initially planned to cremate remains that had been exhumed from World War II massacre sites in Siglap. When it emerged that some remains could possibly have belonged to Muslim soldiers of the former Straits Settlement Volunteer Corps, Prime Minister Lee and the IRO intervened, persuading the Chamber to leave them intact instead.26 These remains were eventually interred in urns beneath the Civilian War Memorial, which was consecrated by representatives of the IRO during a dedication service on 15 February 1967.27

Leaders of the IRO praying during the unveiling ceremony of the Civilian War Memorial, 15 February 1967.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Force For Good

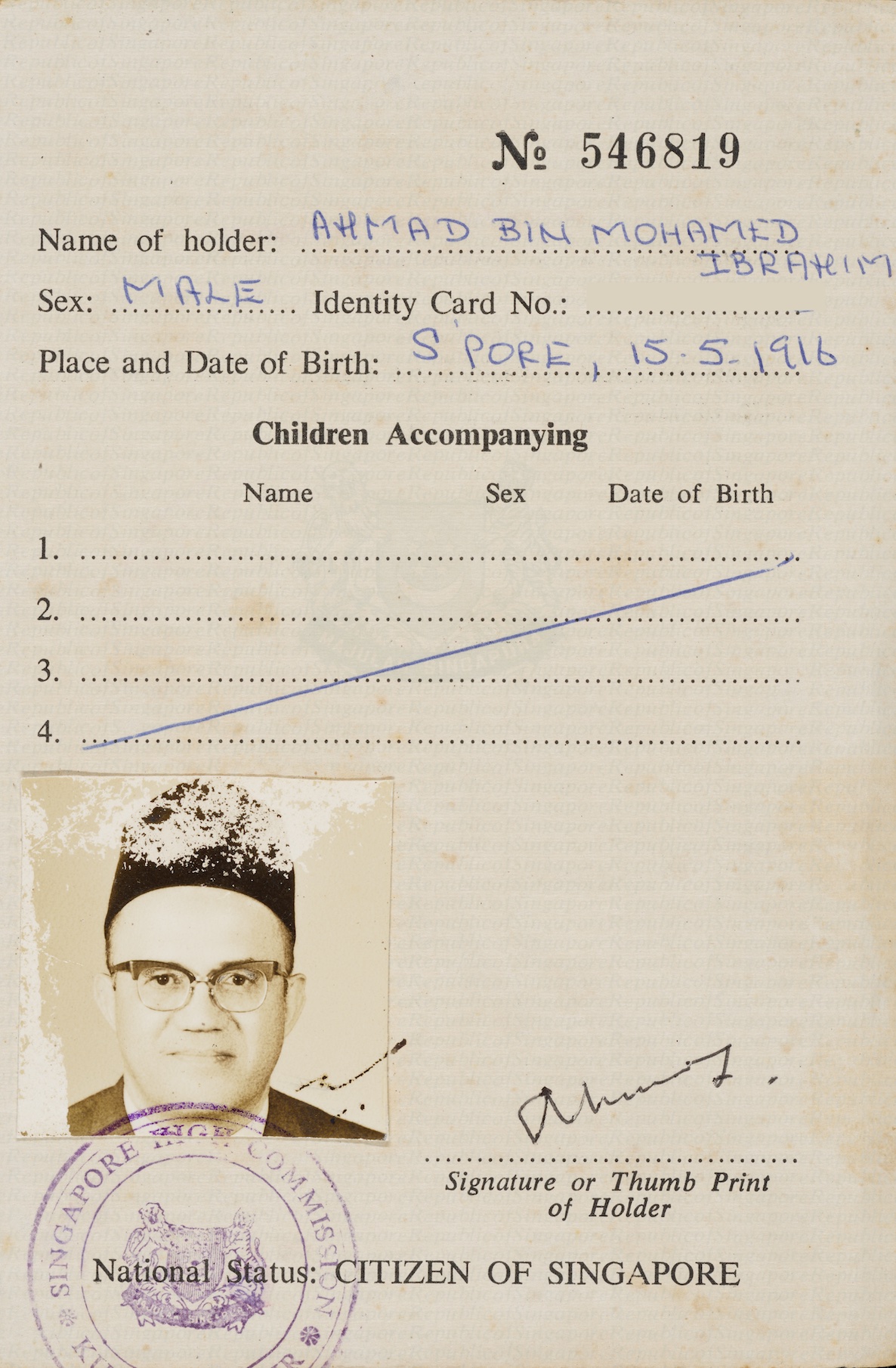

With Singapore developing rapidly post-independence, the IRO continued to partner national institutions in promoting causes beyond the field of religion, demonstrating how religious groups can be mobilised as a force for good. In 1977, the IRO responded to the Singapore Anti-Narcotics Association’s (SANA) call for representatives from different religious groups to care for ex-addicts amid growing concern about drug addiction among youth.28 Two years later, with rising number of tourists visiting religious institutions, the IRO stepped forward to draw up etiquette guidelines that were forwarded to the then-Singapore Tourist Promotion Board.29 IRO council members also contributed in their own ways to Singapore’s broader development. For example, D. D. Chelliah and Francis Thomas both served on the Presidential Council of Minority Rights, while Ahmad Ibrahim served with distinction as independent Singapore’s first Attorney-General.

|

Ahmad Mohamed Ibrahim, Singapore’s Top Legal Officer A lawyer by training, Ahmad Ibrahim helped draft the IRO’s constitution as one of its founding members.30 During the Maria Hertogh crisis, he represented Mansoor Adabi, who had wedded Nadra (or Maria) under Muslim law, in court.31 He later served as Singapore’s State Advocate-General from 1959 to 1965, and independent Singapore’s Attorney-General from 1965 to 1967. As Singapore’s top legal officer, he contributed to the 1961 Women’s Charter, weighed in on sensitive deliberations relating to Merger, and formulated the 1966 Administration of Muslim Law Act.32 According to Dr Goh Keng Swee, Ahmad Ibrahim was a man of “tremendous breadth and depth of intellect, whose ability as a legal draftsman [was] unsurpassed in this country”.33

Lawyer’s wig, passport, and passport annex page belonging to State Advocate-General (later Attorney-General) Ahmad Ibrahim, 1950s–1970s. Gift of the family of Ahmad Mohamed Ibrahim. Collection of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board. |

Adapting to Developments in the Religious Landscape

Even as the IRO continued its good work, by the late 1980s, developments in post-independent Singapore’s religious landscape would prompt a shift in the government’s approach to safeguarding religious harmony. This turn by the government towards a more proactive, hands-on stance was signalled by President Wee Kim Wee when he addressed Parliament during its opening on 9 January 1989. In his speech, Wee highlighted the need for “ground rules” to guide the maintenance of religious harmony, the importance of tolerance and moderation, as well as the need to keep religion and politics separate.34

By the end of that year, a White Paper on the Maintenance of Religious Harmony was presented in Parliament. Two IRO members—Reverend Dr Anne Johnson, representing the Presbyterian community, and the Mufti of Singapore Syed Isa Semait, representing the Muslim community— provided oral and written submissions to a Parliamentary Select Committee, and the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act (MRHA) subsequently came into effect on 31 March 1992.35 The Act sought to “prevent religious tensions and conflict caused by insensitive and provocative acts, and to promote understanding, moderation, tolerance and respect for other religions”.36 It also created the Presidential Council for Religious Harmony as an advisory body to oversee matters affecting the maintenance of religious harmony in Singapore.37

While the state has never had to invoke its powers under the MRHA, safeguarding religious harmony in Singapore remains a work in progress, especially with a rapidly evolving global situation. The MRHA was updated on 7 October 2019 to help the government respond effectively to incidents of religious disharmony and strengthen our safeguards against foreign influence.38

Disagreeing Better

Fast forward to today, and the blossoming of civil society in Singapore has resulted in renewed energy, vigour, and purpose in the field of religious harmony. While the IRO continues to remain active in the inter-religious space, it now partners with a growing array of national and community organisations to strengthen Singapore’s broader social fabric. For example, since 2002, the IRO has contributed its voice to the National Steering Committee on Inter-Racial and Religious Confidence Circles (IRCCs).39 Now known as Harmony Circles, these networks foster social cohesion by building trust and confidence among different communities both in times of peace and crisis.40 The IRO’s partnership and perspectives have also helped co-create initiatives such as the Harmony in Diversity Gallery at Maxwell Road, a 2016 initiative spearheaded by the Ministry of Home Affairs to promote deeper understanding of different faith communities.41

Established voices like the IRO aside, newer outfits such as Roses of Peace (2012), Interfaith Youth Circle (2015), hash.peace (2015), and Dialogue Centre (2022) have further enriched and enlivened inter-religious discourse in Singapore. In a 2023 interview with The Peak, Mohamed Irshad, Roses of Peace’s founder, shared that the initiative was born at a time when news of Charlie Hebdo’s caricatures of Prophet Muhammad was gaining traction in the press.42 Not content with inaction, Irshad led a group of Singapore Management University (SMU) undergraduates to hand out roses and messages of peace from different religions to members of the public—a gesture they found meaningful.43 In a separate 2020 podcast hosted on Tatler Asia, Noor Mastura, the founder of Interfaith Youth Circle, similarly cited the simple desire to “change the world—one world at a time” as a powerful source of motivation. To her, the goal of dialogue may not even be to get participants to agree to disagree, but rather, to simply “disagree better”.44

Practitioners of various faiths at an inter-religious dialogue titled “Common Senses for Common Spaces”, 8 August 2021.

The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Conclusion: A Personal Perspective

I joined the Interfaith Society when I was an undergraduate at the National University of Singapore (NUS) between 2014 and 2018. During those years, I participated in fortnightly dialogues with fellow university students, attended events organised by the IRO, and helped in outreach to the general public. Through my involvement in inter-religious dialogue, I have learnt that getting involved is important no matter what stage of life one may be at. While exposure to other faith practices may be eye-opening for those without friends of a different religious background, it may also be refreshing for those who simply wish to better understand different perspectives.

For me, what was particularly meaningful was being invited to the events of other religious groups, such as the NUS Buddhist Society, and learning about their beliefs and practices even at events which were not inter-religious in nature. Until today, I still remember sitting in a room, in awe of the deep chanting in Pali while witnessing everyone in their moment of devotion. So long as such experiences take place in a respectful atmosphere, I think they should feature regularly in our lives, as we can then better appreciate the beauty of the diversity that we all share in Singapore.

Over the years, I have also seen the nature of dialogue evolve. While people may naturally be more comfortable talking about similarities across religions and emphasising the importance of mutual tolerance, more are recognising that conversations about differences, when done in a respectful way, can help foster deeper understanding and cross-cultural appreciation. This shows how our approach towards inter-religious dialogue has matured over time as well.

Postscript

Since the establishment of the IRO in 1949, efforts to promote and maintain religious harmony in Singapore have kept pace with changing political and socio- historical contexts. With the ever-evolving global religious landscape, the threats to Singapore’s religious harmony will also continue to intensify. If the history of the IRO is any guide, it is only through the persistent efforts of all—both the government and society—that genuine inter-religious understanding, tolerance, and appreciation can continue to be fostered.

IRO representatives conducting prayers during an annual National Day observance ceremony at the Fullerton Hotel, 19 August 2025.

Lianhe Zaobao © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

NOTES

-

William Miner, “In Singapore, Religious Diversity and Tolerance Go Hand in Hand”, Pew Research Center, 6 October 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/10/06/in-singapore-religious-diversity-and-tolerance-go-hand-in-hand/ (accessed 29 August 2025).

-

Nathene Chua, “Public Efforts or Private Pursuit? An Early History of the Inter-Religious Organisation in Singapore, 1949-1965” (B.A. thesis, National University of Singapore, 2018), 13, 17.

-

“Muslim Divine for Colony”, The Straits Times, 14 December 1948, 4. “Maulana” is an honorific title used mostly in South Asia to address respected Muslim religious scholars.

-

H. B. Amstutz and Ahmad bin Mohamed Ibrahim, eds., The Contribution of Religion to Peace (Singapore: Malaya Publishing House Limited, 1949), 9-10.

-

“A Brief History of IRO”, Inter-Religious Organisation Singapore, https://iro.sg/history/ (accessed 28 August 2025).

-

Amstutz and Ahmad, Contribution of Religion to Peace, 3.

-

Lai Ah Eng, “The Inter-Religious Organisation of Singapore”, in Religious Diversity in Singapore, edited by Lai Ah Eng (Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2008), 608.

-

Amstutz and Ahmad, Contribution of Religion to Peace, 3.

-

IRO-40: Inter-Religious Organisation Singapore 40th Anniversary Commemorative Book (Singapore: Inter-Religious Organisation, 1990), 4.

-

Amstutz and Ahmad, Contribution of Religion to Peace, 8-10.

-

“We Need These Qualities — Black”, The Straits Times, 26 May 1956, 5.

-

Khairudin Aljunied, Colonialism, Violence and Muslims in Southeast Asia: The Maria Hertogh Controversy and its Aftermath (New York: Routledge, 2009), 22.

-

“Religious Bodies Condemn Riots”, The Straits Times, 12 January 1951, 7.

-

“A Creed for All Men”, The Straits Times, 24 December 1950, 10.

-

“Appeal by Council of Inter-Religious Organisations of Singapore Following Disturbances in the Geylang Serai Area” (radio broadcast, Singapore, 9 September 1964), National Archives of Singapore, Accession No. 2006002268.

-

Mehervan Singh, interview by Pitt Kuan Wah, Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore, Accession No. A000553, Reel 34, 12 July 1985.

-

Lai, “The Inter-Religious Organisation of Singapore”, 608.

-

A. K. Isaac, “Hon. Secretary’s Report”, 10 October 1955, Inter-Religious Organization (Singapore and Johore Bahru), National Archives of Singapore, 471-55 (hereafter cited as NAS 471-55); IRO, “Minutes of General Meeting”, 5 August 1955, NAS 471-55.

-

IRO-40, 41.

-

IRO, “Minutes of Council Meeting”, 13 July 1956, NAS 471-55; IRO, “Minutes of General Meeting”, 16 August 1956, NAS 471-55.

-

George K. Seow for the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Culture to the Secretary of IRO, 19 October 1959, Inter Religious Organization, National Archives of Singapore, 92-59; “Prayers by All for State of S’pore”, The Straits Times, 3 June 1960, 4; Lai, “The Inter-Religious Organisation of Singapore”, 615.

-

Lee Kuan Yew, “Transcript of the Prime Minister’s Statement to Religious Representatives and Members of the Inter-Religious Council at His Office in City Hall” (speech, Singapore, 30 September 1965), National Archives of Singapore, lky19650930a.

-

Lee, “Transcript of the Prime Minister’s Statement to Religious Representatives and Members of the Inter-Religious Council at His Office in City Hall”; Lai, “The Inter-Religious Organisation of Singapore”, 611.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 18, Col. 1285-1286, 15 March, 1967.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 25, Sitting No. 18, Col. 1285-1286, 15 March 1967.

-

Singh, interview, Reel 34.

-

“War Memorial is Unveiled”, The Straits Times, 16 February 1967, 17.

-

IRO-40, 42.

-

Lai, “The Inter-Religious Organisation of Singapore”, 614.

-

Lai, “The Inter-Religious Organisation of Singapore”, 622.

-

Ahmad Nizam Abbas, “Ahmad Ibrahim’s Role in Shaping Islamic Laws in Singapore — From Colonial to Post-Colonial”, in Beyond Bicentennial: Perspectives on Malays, edited by Zainul Abidin Rasheed, Wan Hussin Zoohri, and Norshahril Saat (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2020), 568.

-

Ahmad Nizam, “Ahmad Ibrahim’s Role in Shaping Islamic Laws in Singapore”, 565.

-

Ahmad Nizam, “Ahmad Ibrahim’s Role in Shaping Islamic Laws in Singapore”, 573.

-

White Paper on the Maintenance of Religious Harmony, 1989, Cmd. 21.

-

Lai, “The Inter-Religious Organisation of Singapore”, 612; Jean Lim, “Maintenance of Religious Harmony Bill”, Singapore Infopedia (National Library Board), https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=3edc3e5f-7333-4ae9-ba2d-7c355c4a1cee (accessed 29 August 2025).

-

Lim, “Maintenance of Religious Harmony Bill”.

-

Ministry of Information and the Arts, The Need for the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act (Singapore: Resource Centre, Publicity Division, Ministry of Information and the Arts, 1992), 4.

-

Grace Ho, “Parliament: Updates to Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act Timely Given External Environment, Says Shanmugam”, The Straits Times, 7 October 2019, https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/parliament-updates-to-maintenance-of-religious-harmony-act-timely-given-external (accessed 29 August 2025).

-

Lai, “The Inter-Religious Organisation of Singapore”, 615.

-

“Racial and Religious Harmony Circle”, Ministry of Culture, Community & Youth, 27 May 2025, https://www.mccy.gov.sg/sectors/community/racial-and-religious-harmony-circle (accessed 29 August 2025).

-

“About the Gallery”, Harmony In Diversity Gallery (Ministry of Home Affairs), https://www.harmonyindiversitygallery.gov.sg/about/ (accessed 29 August 2025).

-

Charlie Hebdo is a French satirical magazine that published cartoons depicting Prophet Muhammad, which Islam generally prohibits.

-

Reeta Raman, “The Peak Power List 2023: Roses of Peace Founder Mohamed Irshad Plans to Change the Minds of Youth, One Interfaith Conversation at a Time”, The Peak, 23 October 2023, https://www.thepeakmagazine.com.sg/people/mohamed-irshad-the-peak-power-list-2023 (accessed 29 August 2025).

-

Lee Williamson, “Noor Mastura— Empowering Communities to Make Change”, Tatler, 29 July 2020, https://www.tatlerasia.com/gen-t/leadership/crazy-smart-asia-noor- masturaempowering-communities-to-make-change (accessed 29 August 2025).

***

Sharifah Afra Alatas is Senior Research Officer at the ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, where she does research on socioreligious and sociopolitical issues among Muslim societies in Southeast Asia, with a particular focus on Malaysia. Beyond her day job, she conducts sharing sessions about Arab heritage in Singapore.

***

This article is featured in the Founders’ Memorial’s +65 publication, Volume 4 — the flagship publication that aims to build thought leadership on Singapore’s independence and post-independence history and society. This issue explores multiculturalism, offering broader context on its origins and evolution in independent and post-independent Singapore (1950s–1970s). Limited copies are available at the Not Mere Spectators: The Makings of Multicultural Singapore exhibition. Download your online copy here.