Not Mere Spectators > Article - S. Rajaratnam: Keeper of the Multiracial Flame

S. Rajaratnam:

Keeper of the Multiracial Flame

Irene Ng

S. Rajaratnam with a lion dance troupe at Kampong Glam Community Centre, 11 June 1967.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Among Singapore’s founding leaders, S. Rajaratnam stood out for his revolutionary conception of multiracialism. From the very beginning, it was he who drove the bold experiment to inculcate in the diverse peoples a sense of national consciousness that transcended the boundaries of race, language, and religion. His crusade, which went against the political currents at the time, set the ideological trajectory that left the most lasting mark on the nation.

While the other first-generation leaders subscribed to this ideal, none could be said to be as ardent or as audacious as Rajaratnam in seeking to entrench it into the nation’s core and to live up to its full rigour.

He was an iconoclast who confronted the deep divisions between the different races and challenged all sorts of traditional assumptions about race, culture, and language.

From the outset as Singapore’s first Minister for Culture in 1959, he set out to achieve this vision: Singapore would not be a nation divided by communal pulls and communal politics. It would be a nation united by a common national identity and a common purpose: to build a fair and just society, regardless of race, language, or religion.

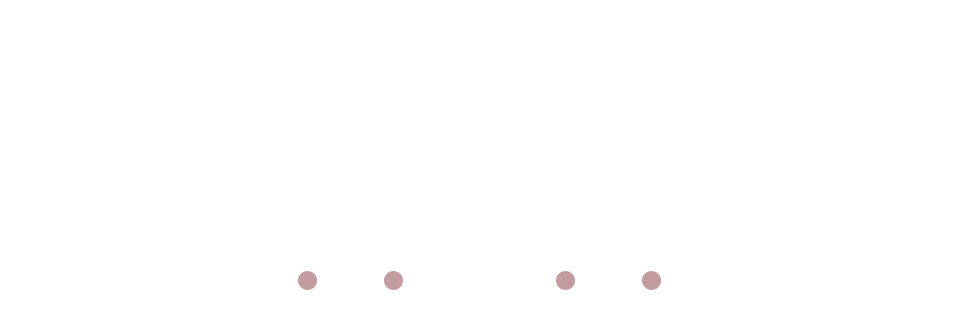

Citizenship Registration certificates issued to S. Rajaratnam and his wife Piroska Rajaratnam, 1958.

S. Rajaratnam Private Papers, courtesy of ISEAS Library, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.

In his first address to the Legislative Assembly on 21 July 1959, Rajaratnam, known as the ideologue in the founding Cabinet, spelt out the underlying basis of his non-communal vision: that “the shape of a man’s nose, the cut of his eyes, the colour or the texture of his hair, are not a sound basis on which to build a political or an economic philosophy. Neither can political and economic problems be solved by reference to something which we just got through the accident of birth—our skin, our colour, and the shape of our eyes.”1

In other words, in politics and economics, racial considerations do not enter. It does not matter where you were born, which culture you came from, the colour of your skin. What matters is that your first and last loyalty is to the country.

The objective elements of the national identity—clothing and food, for example— were to him secondary matters. The subjective elements—the dominant will and the moral aspects—are primary and even more than that, paramount. It requires an act of faith, and a deliberate act of will.

At the heart of this vision is a distinctly Singaporean brew of multiculturalism. It is not about multiple ethnic groups coexisting with each other on the island. Rather, it is about them sharing a common national identity to which all give their primary loyalty.

When first introduced, that was a truly revolutionary idea, one that went against the experiences and mindsets of the general public. Most of the inhabitants were new immigrants, from China, India, and other parts of the region. Their loyalties were fiercely to their kin, clan, and motherland. Racial stereotypes were rife, as were prejudices.

In demanding that the people change their communal worldview and acknowledge each other’s humanity and equality, Rajaratnam disrupted the status quo. For the people at the time, it was an entirely new way of viewing the country’s reality and their future in it.

S. Rajaratnam speaking at a People’s Action Party (PAP) rally at Chinatown, 26 April 1959.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The most fundamental problem, at least as far as Rajaratnam was concerned, was the deep-seated communal tensions and inequalities left behind by the British divide- and-rule policy.

As he warned in September 1959: “With the transfer of political power from the British, there is the ever-present danger of the struggle for political and economic power degenerating into communal rivalry, and, if uncontrolled, unto communal conflict.”2 He thus made it the primary task of the Ministry of Culture “to instil in our people of all races the will to be a nation”.

Not merely a cultural policy, it was an ideology for national survival. He was convinced that a shared national identity was the only effective defence against communal conflict, which would all but destroy Singapore.

From all conceivable angles, shaping a non- communal Singapore was a delicate affair. Arrayed against it were, as Rajaratnam once put it, “oily-tongued communal demagogues” out to stir up age-old communal prejudices and fears among the people, pitting race against race for political power.3

Despite the scale of the challenge, Rajaratnam firmly believed that people can be taught to identify themselves with Singapore first and last. After all, racial consciousness was not in the blood, but in the culture: “In fact, a child has to be tutored into believing that he is a Chinese, Malay, or Indian.”4 Thus, with the right education policy and sociocultural environment, children can be taught to instead identify with the nation first, and emerge as Singaporeans. His hope, as always, lay with the younger and future generations.

He also had faith in the power of reason. Rather than encouraging people to see race/ethnic groups as fixed and definitive categories, they should be made to understand and accept the ways in which the different cultures affected and modified each other. Just as there was no such thing as a pure race with ceaseless migrations of people since pre-historic times, there were no pure cultures, unmixed with others. If people would only realise this, they would know it was senseless to fight among themselves as if the race/culture categories were absolutes, eternal, or sacred.

S. Rajaratnam posing with young Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat performers of different races, 5 June 1960.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The basic premise underpinning his vision of multiracialism is that race, culture, and language were man-made constructs. So were political, social, and economic problems, which could therefore be unmade and overridden by men.

In private, Prime Minister (PM) Lee Kuan Yew, who himself believed that differences of race were primordial and genetic and therefore hard to overcome, nursed doubts about how realistic Rajaratnam’s self-defined mission was. But publicly, PM Lee went along with his Culture Minister’s position. He said later: “He believed in it and took that line. So we acquiesced.”5

It is important to be clear, however, that by seeking to create a non-communal nation, Rajaratnam did not mean that he wanted to destroy the people’s cultural traditions, or to erase their cultural heritage. What he fought against were racial/cultural chauvinism, racial politics, and the idea that people should draw their primary identity from their ethnic roots or their ancestral origins.

His multicultural model in fact celebrates the diversity of the various cultures, but gives precedence to the shared national identity over other affiliations and to national interest over communal interests.

Given the urgent imperative of uniting the people, Rajaratnam had pursued a policy of “laying stress on those things which unite the races rather than those which divide them”.6 This came to the fore in the first major nation-building exercise that he masterminded in December 1959: the historic National Loyalty Week.

Rajaratnam described the collective experience this way: during that period, the people “forgot” that they were Malays, Chinese, Indians, and Eurasians. “We experienced for the first time on a mass scale that we were one people, bound together by a common destiny. For the first time in our history, we understood what it means to say ‘my country, my people’”, he said.7 In retrospect, the moment probably represented the first flickering of a national consciousness. Yet how fragile that sense of unity was. This was demonstrated by the seeming ease with which racial sentiments could be whipped up to incite riots—as it did in 1964 when Singapore was part of Malaysia.

As the race riots raged, Rajaratnam could not help but fear for his core vision of a non-communal system. As he revealed later, “during the riots, I thought it would all collapse”. It is important to remember that fear, that desperation.8

When that battle resulted in Singapore’s expulsion from Malaysia in 1965—forcing it to become independent on its own—it boded ill for the PAP’s non-communal vision when the Chinese began demanding dominance in language and culture. Meanwhile, Malay ultras from the Federation clamoured for special rights for Malays in Singapore.

S. Rajaratnam assuring Muslims taking refuge in Sultan Mosque as he toured the riot-stricken areas of Kampong Glam with Dr Toh Chin Chye on 24 July 1964.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

S. Rajaratnam and PM Lee Kuan Yew meeting with other representatives of the Malaysian Solidarity Convention, 10 August 1965.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Malaysian Solidarity Convention booklet, 1965.

Collection of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

The choice before the founding leaders was stark: give in to the communal pressures, or use that pivotal moment to bolster national solidarity. It took strength and courage to choose the latter and persist in the face of opposition, problems, and disaster.

|

Original Role Model

Regardless of race, language, or religion.

For Rajaratnam, that phrase was not an abstract political philosophy, or a distant national ideal. It was a way of life.

This was demonstrated most clearly in his choice of wife—a white European woman named Piroska Feher, whom he married in 1943. Their interracial union defied the era’s social norms and challenged deeply ingrained prejudices in Malaya and Singapore.

Their relationship crossed deep cultural divides. Ceylon-born Rajaratnam was raised as a Hindu in a strict caste-conscious Jaffa Tamil household in Seremban, and spoke English, Tamil, and Malay. Piroska was raised as a Lutheran in Hungary, where she was born, and spoke Hungarian, German, and English.

They had met in London in 1938 in socialist circles. He was a law undergraduate, and she was a refugee working as an au pair. When they tied the knot in the midst of World War II, he was 28; she 31.

Their union suffered ostracism, prejudice, and gossip from Rajaratnam’s family and the wider Jaffa Tamil community after they returned to Malaya in 1947. Arranged marriages within the clan was the norm; marrying outside one’s race and faith was a taboo.

The couple also had to cope with political threats and pressures from communal chauvinists after Rajaratnam joined politics in 1959 and championed his non-communal vision for the nation. Even up to the 1990s, he continued to receive hate mail from bigots mocking him for marrying a white woman. Piroska suffered too, such as the time in 1959 when Chinese-educated conservative forces whipped up anti-West sentiments, forcing her to leave Singapore for a few months.

Despite all the trials, the couple shared a deep and enduring love that testified to their ability to transcend ethnic boundaries. If ever there was a founding leader who embodied the very essence of Singapore’s multiracial creed, it was Rajaratnam. He was the original role model.

S. Rajaratnam and his wife, Piroska Rajaratnam in London, 1940s. S. Rajaratnam Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. |

Although shattered by the Separation, Rajaratnam appeared at the United Nations as Singapore’s founding Foreign Minister a month later, in September 1965, with a bold narrative of the country’s multiracial vision: “We think of ourselves not as an exclusively Chinese, Indian or a Malay society, but as a little United Nations in the making.”9 Singapore, he added, would “bring to the United Nations the attitudes and approaches of a multiracial nation aware that independence and interdependence of peoples and nations are not incompatible goals to pursue”.10 It was a historic speech that set the tone and template for the country’s foreign policy as well as its national ideology.

Mere months later, in February 1966, he embedded this ideology into the Singapore Pledge that he drafted. As Lee Kuan Yew confessed later, the Pledge was something that he would not have been able to “even conceive of” at the time. “Given the mood of the people in Singapore at that time,” he observed, “only Raja had the conviction and optimism to express those long-term aspirations in that pledge.”11

Although Rajaratnam’s multiracial vision appeared overly idealistic to some, his was not an airy-fairy, pie-in-the-sky model. It was a muscular, gritty one based on a tough appreciation of the dangers of racial politics and the evils of racial ideologies. As he reminded the Legislative Assembly in 1961, as long as “old suspicions and fears” were alive, so too was the danger of communalism. “It is like a wild and hungry beast pacing impatiently behind the bars of a cage. We who bear no hatred against races and creeds intend that this wild beast remains locked in its cage so that eventually it will waste away and die.” The price of racial peace, he said, is “eternal vigilance”.12

S. Rajaratnam and Dr Toh Chin Chye representing Singapore for the first time at the United Nations, September 1965.

Toh Chin Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

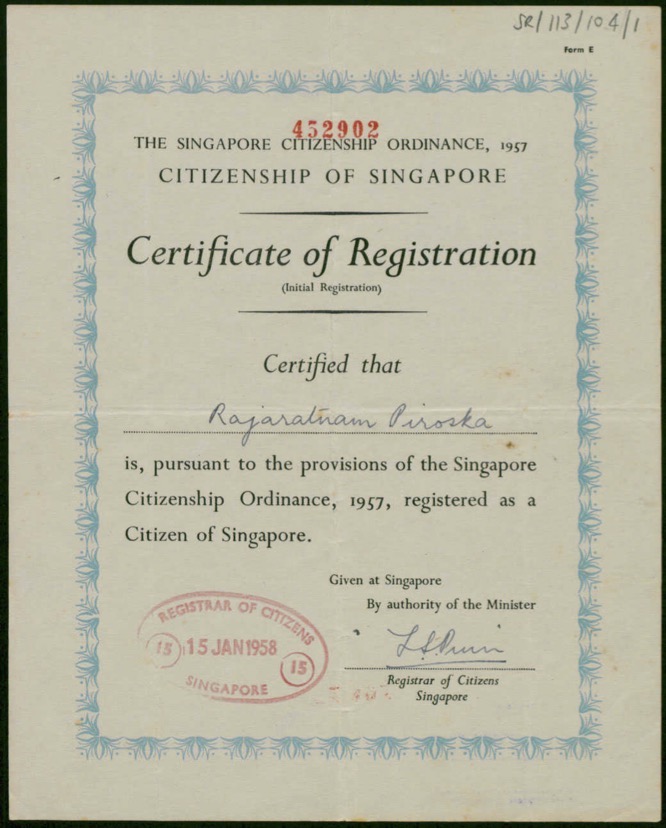

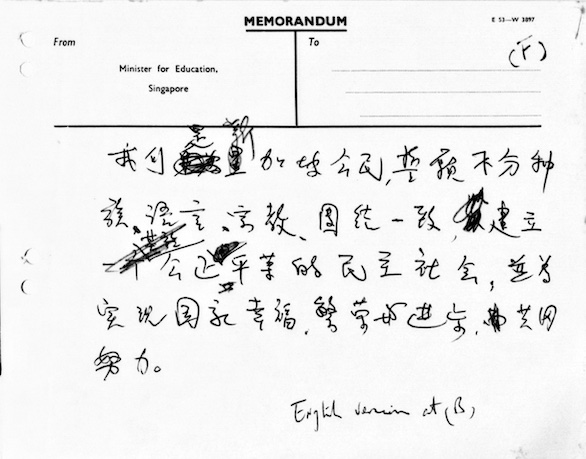

Initial handwritten translations of the National Pledge into Chinese, Malay, and Tamil, 1966.

Ministry of Education Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Rajaratnam would not hesitate to nip in the bud manifestations of ethnic nationalism, whether under the guise of religious freedom, promotion of ethnic culture, or concern for one’s ancestral roots. For this, the Internal Security Act (ISA), which allows detention without trial, was an effective tool. As he said in 1987, “As one who has been associated with the government since 1959, I am absolutely convinced that without ISA, it would be virtually impossible to preserve a multiracial and multireligious society against the danger of tribal wars.”13

The painful reality—one that obsessed the Foreign Minister—was that Singapore’s multiracial and multilingual fault lines could be its Achilles heel. For him, there were few nightmare scenarios worse than ethnic bloodshed and anarchy: what if, under the external and domestic pressures, the people in Singapore responded not as Singaporeans, but as Malays, Chinese, Indians, and others?

In 1987, he warned that tribal politics could emerge in Singapore if the “popular mood changes and you have a weak-kneed government prepared to go along with the popular tide”—or worse, groups and political parties that deliberately created a political and psychological climate conducive to sparking tribal wars.14

To navigate these global shifts, he believed what was required was a greater, not lesser, role for the government in formulating and promoting policies that strengthened Singapore’s national identity. And, as ever, eternal vigilance.

|

Seen and Heard in Not Mere Spectators: The Makings of Multicultural Singapore

Exchange of Letters on The National Pledge

Six months after Independence, Minister for Education Ong Pang Boon wrote to Minister for Foreign Affairs S. Rajaratnam to seek his views on two versions of a pledge for school flag-raising ceremonies. The pledge was part of broader efforts to nurture national consciousness and patriotism among students then.

Two weeks later, Rajaratnam replied to Ong with his version, re-writing it almost entirely. His draft changed the entire premise of the pledge from the individual “I” to the collective “we”, and emphasised a multiculturalism that disregards the differences of race, language, and religion. The version we recite today, which opens with “We, the citizens of Singapore” and includes the line “regardless of race, language or religion”, does not ask us to forget our differences, but to embrace our common identity.

Correspondence between Ong Pang Boon and S. Rajaratnam on a Pledge for flag-raising ceremonies in schools, 1966. Ministry of Education collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

|

In Cabinet, Rajaratnam provided a powerful countervailing influence which checked any impulse to revert to ethnic-based policies. When the idea for the first self- help group, the Council on Education for Muslim Children (or MENDAKI) was mooted in Cabinet in 1981, he argued that it should be presented as a multiracial effort.15 PM Lee did take this line when he addressed the first MENDAKI Congress in 1982.16

In the 1990s, after Rajaratnam left politics, there was a changing of the guard. Ever watchful, he became concerned with policies which encouraged Singaporeans to assert their ethnic identities. Other ethnic self-help groups were formed with the backing of the government: Singapore Indian Development Association (SINDA) and the Chinese Development Assistance Council (CDAC).17

The trend worried him. Time and again, Rajaratnam had argued that minority groups would ultimately lose out should they go in for such communal-based policies, for it would only invite and encourage the majority community, the Chinese, to do the same.

He warned in 1983: “Once the minorities do this, they would relieve the majority community of the responsibility of being equally responsible for the welfare of the minority communities as they are for the majority community.”18

He was also disturbed by the increasing emphasis placed on the Chinese-Malay- Indian-Others (CMIO) categorisation in one’s Identity Card (IC) for policy implementation. These categories are rooted in a rigid conception of races as objective and fixed. He feared that such perspectives, which freeze racial differences, would set back the progress towards an ever-evolving Singaporean Singapore.

Rajaratnam had long considered the racial category in the IC as a mere bureaucratic technicality inherited from the British, and largely irrelevant to daily life in independent Singapore. He himself did not place much store on his artificial—and incorrect— classification as an “Indian”. He was in fact Ceylon Tamil, not Indian.

A front page report in Berita Harian on S. Rajaratnam’s support for MENDAKI with a $10,000 donation from his constituency Kampong Glam to signal a national and multiracial approach, 20 August 1982.

Berita Harian © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Ultimately, forging a united multiracial nation was for him a moral project. As he said later: “On my IC, it says my race is Indian. But I don’t care if you call me an Indian or an Eskimo. What is important is whether you consider me a good man.”19 In other words, being Singaporean transcends racial categories and geographical boundaries.

In essence, it is about shared values and a sense of fellow feeling towards others, regardless of their race, language, or religion, in a world in which nations are becoming increasingly interconnected as one global community.

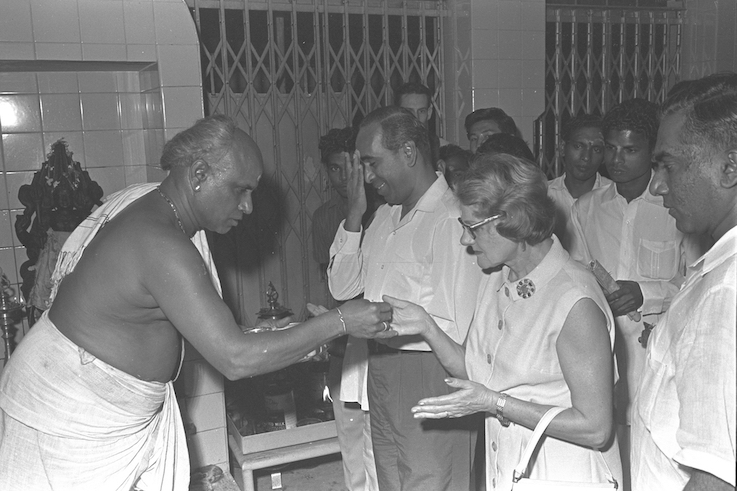

S. Rajaratnam and Piroska Rajaratnam attending Thaipusam celebrations at Sri Thendayuthapani Temple, 18 January 1965.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Right to the end of his life, Rajaratnam was championing his vision of a Singaporean Singapore. As he reiterated in 1990, two years after he retired from politics: “Being Singaporean is not a matter of ancestry. It is conviction and choice.”20 His vision never changed; his will never wavered. For as long as he lived, he was the keeper of the multiracial faith.

The last time I interviewed him in the 1990s—when he was in his 80s—I saw that the flame still burned, because he believed it could not be allowed to go out. A series of minor strokes had slowed him down and his voice was quiet. But his eyes gleamed when he spoke about the progress made in building a successful, multiracial Singapore. He considered it the foundation stone of Singapore. Destroy this foundation stone, and Singapore crumbles into anarchy and ruin.

So let it be understood that, for Rajaratnam, it is not a matter of merely reciting the National Pledge. Most important is instead the emotions and moral imperative that go with it, the experience that it is present and real—and the conviction, the faith that it will be upheld for future generations.

S. Rajaratnam and the author, Irene Ng, at his house in Chancery Lane, 1997.

Courtesy of Irene Ng.

NOTES

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 11, Sitting No. 6, Col. 321-322, 21 July 1959.

-

“Malayan Culture: A Reply to Sceptics”, Sunday Mail, 27 September 1959, 1.

-

“PAP Pledge to Stamp Out Communal Fires”, Singapore Standard, 20 April 1959, 5. Rajaratnam expounded on the dangers of communal-based parties and communal leaders in pre-election rallies in 1959 where he outlined the PAP’s plans to stamp out communalism.

-

S. Rajaratnam, “Speech titled ‘Ethnicity and Singaporean Singapore’ delivered at National University of Singapore Society” (speech, Singapore, 14 June 1990), S. Rajaratnam Private Papers, ISEAS Library, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, SR.094.012.

-

Irene Ng, S. Rajaratnam, The Authorised Biography (Volume 1): The Singapore Lion (Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2010).

-

“Literature Can be Common Link to Bind Various Races—Mr. R”, The Straits Times, 23 November 1959, 4.

-

“Keep Up the Spirit of Loyalty and Unity—Mr. R”, The Straits Times, 10 December 1959, 4.

-

The Singapore government’s hands were tied as, under the Merger agreement, internal security was under the Central government in Kuala Lumpur.

-

United Nations General Assembly Official Records, 20th Session, 1332nd Plenary Meeting, 21 September 1965.

-

For a fuller account, see Irene Ng, S. Rajaratnam, The Authorised Biography (Volume 2): The Lion’s Roar (Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2024), Chapter 10.

-

Ng, The Singapore Lion, xiii.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 14, Sitting No. 12, Col. 945-946, 11 January 1961.

-

S. Rajaratnam, “Speech at the Opening of the Seminar on ‘Tamil Language and Tamil Society’ at the National University of Singapore” (speech, Singapore, 18 July 1987), National Archives of Singapore, SR19870718s.

-

S. Rajaratnam, “Speech at the Opening of the Seminar on ‘Tamil Language and Tamil Society’ at the National University of Singapore”.

-

Yayasan MENDAKI is also known as the Council for the Development of the Singapore Malay/Muslim Community today. Rajaratnam supported the formation of MENDAKI as a task force formed to look into measures to improve the educational level of the Malays in Singapore. Most Malays had low education levels, which in turn affected their occupational status and standard of living. Rajaratnam himself had been concerned with this problem for some time, which he put down largely to the historical circumstances of the Malays from the British colonial days. What he resisted was taking a narrow communal approach towards it. See Ng, The Lion’s Roar, 672.

-

Lee Kuan Yew, “Address at the Opening Ceremony of the Congress of the Council on Education for Muslim Children (Mendaki) held at Singapore Conference Hall” (speech, Singapore, 28 May 1983), National Archives of Singapore, lky19820528b.

-

In Singapore’s official records, race and ethnicity are conflated, with each individual assigned a race and a mother tongue.

-

S. Rajaratnam, “Speech at the Opening of the Taman Bacaan Youth Leadership Course held at the National Youth Leadership Training Institute” (speech, Singapore, 29 April 1983), National Archives of Singapore, 19830429_0001.

-

“There’s No Racism in Singapore, Says Raja”, The Straits Times: Weekly Overseas Edition, 15 September 1990, 3.

-

“‘Remembering’ Ancestral Heritage is Building Ghettos in the Minds of the Community”, The Straits Times, 9 October 1990, 28.

***

Irene Ng is the authorised biographer of S. Rajaratnam. She wrote his two- part biography The Singapore Lion and The Lion’s Roar, and compiled the anthology The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam.

She was formerly a journalist and a Member of Parliament. She is now a full-time writer.

***

This article is featured in the Founders’ Memorial’s +65 publication, Volume 4 — the flagship publication that aims to build thought leadership on Singapore’s independence and post-independence history and society. This issue explores multiculturalism, offering broader context on its origins and evolution in independent and post-independent Singapore (1950s–1970s). Limited copies are available at the Not Mere Spectators: The Makings of Multicultural Singapore exhibition. Download your online copy here.