Not Mere Spectators > Article - Aneka Ragam Ra'ayat: Bringing to Life a Multicultural Nation

Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat:

Bringing to Life a Multicultural Nation

Pearl Wee

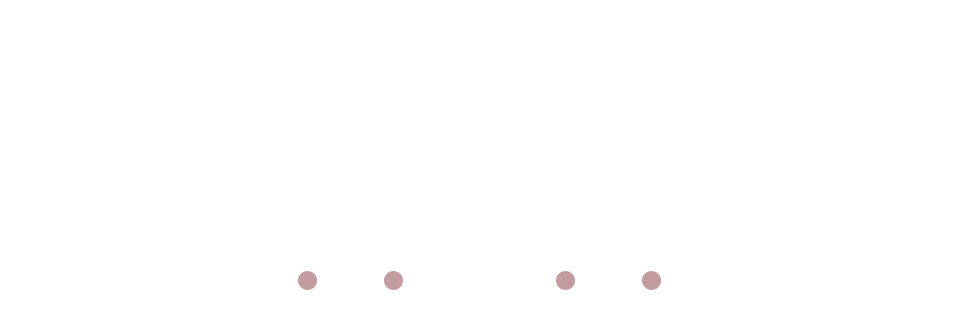

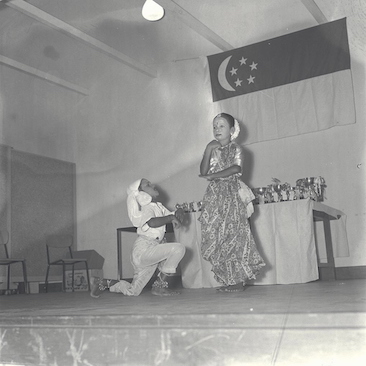

Bharatanatyam, a classical Indian dance, being presented at an Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat on the City Hall steps, 4 June 1962.

The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

The Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat, or People’s Cultural Concerts, were intimately linked with Singapore’s nascent attempts at forging a multiracial and multicultural society. When then-Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong delivered his 2021 National Day Message, he cited these performances as “an early start to [Singapore’s] journey to becoming one people, one nation”.1 Apart from capturing the experimental zeitgeist of a nation in the making, the concerts also breathed life into S. Rajaratnam’s idealistic vision of a distinctly Malayan culture, as shaped by cultural fermentation and artistic expression.

This essay explores the expectant optimism shared by those involved in the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat—a sentiment driven by an ardent belief in Malaya’s (and Singapore’s) multicultural future. It pays tribute to leaders like S. Rajaratnam, Lee Khoon Choy, and Lee Siow Mong, as well as citizen performers like Uma Rajan, Vivien Goh, and Som Said, who helped make the concerts a reality.

Through their participation in this radical project, these individuals helped make tangible the once abstract notion of a Singaporean Singapore. Deemed by some as too ambitious for its time, the vision which inspired the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat nevertheless continues to reverberate each time Singaporeans pledge ourselves as one united people “regardless of race, language, or religion”.2

Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam delivering a speech at an Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat in front of City Hall, 2 June 1963.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A Multicultural Malaya

When Singapore attained self-governance in June 1959, few felt an instinctive sense of attachment to either the city-state, or its wider hinterland of Malaya. With migrants constituting a significant proportion of the population, Singapore found itself divided along racial, cultural, and linguistic lines. As the newly appointed Minister for Culture, Rajaratnam was seized by the need to inculcate a sense of national unity, particularly since colonial policy had hitherto focused on managing society through a policy of “divide and rule”.3

Animated by the possibility of leveraging on culture as a social tool, he found inspiration in the potential of a newly forged Malayan culture which could bind the different races in Singapore and Malaya together. In an August 1959 speech at the University of Malaya titled “Towards a Malayan Culture”, Rajaratnam further articulated his vision of “a Malayan culture” that was “national in scope”. In his view, this culture “should become the property not of one community but of all communities”.4

Rajaratnam’s aspirations for a new, inclusive culture resonated with many of his generation. As early as January 1950, a young Lee Kuan Yew had mused in a speech to the Malayan Forum in London that “the pre-requisite of Malayan independence is the existence of a Malayan society, not Malay, not Malayan Chinese, not Malayan Indian, not Malayan Eurasian, but Malayan, one that embraces the various races already in the country”.5 Meanwhile, at the University of Malaya in Singapore, Wang Gungwu was pouring his energies into an experimental Malayan form of poetry that grafted Malay and Chinese linguistic elements onto an English base.6 Indeed, a range of student and artistic groups in the early 1950s were actively discussing pan-Malayan ideals, with discussions often zeroing in on the form and shape this emergent Malayan identity should take.7 Still, as dismantling colonial rule was the primary focus during those years, incipient differences over the precise contours of this Malayan culture could, at least temporarily, be papered over.

By the middle of the 1950s, post-war constitutional developments that saw Singapore severed from the Malay Peninsula had made the polemics around this issue even more fraught and complex. Notably, by 1957, Malay-majority Malaya had been granted independence, while Chinese- majority Singapore remained a British Crown Colony, albeit enroute to becoming a self-governing state. With the latter’s political future up in the air, the atmosphere in Singapore naturally grew more tense and expectant. This uncertain mood was reflected in the debate on the Yang di-Pertuan Negara’s address when the newly formed Legislative Assembly convened for the first time after self-governance was granted in June 1959. Rising to speak, the Singapore United Malays National Organisation (SUMNO) Assemblyman for Geylang Serai, Abdul Hamid Jumat, questioned pointedly:

“Are we to shape the new nation based on the indigenous people of Singapore, that is the Malays, or is it to be based on the Chinese people, or the Indian people who are inhabitants staying in Singapore? I feel that if I were to forget my feelings as a Malay, it would be difficult. Likewise for the Chinese and the Indian people, it would be difficult.”8

First sitting of the Legislative Assembly, 1 July 1959.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Introducing Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat

Against such a backdrop, Rajaratnam instantly recognised the role his newly established Ministry of Culture could play to integrate and unite people from different races. Working quickly in the months following the swearing in of the first Cabinet, his core team—comprising Parliamentary Secretary Lee Khoon Choy, Permanent Secretary Lee Siow Mong, and Assistant Secretary S. T. Ratnam—set out planning for a series of multicultural concerts “which would eventually bring about new forms in the arts, [and] which [were] not typical or symbolical of any one but [were] a synthesis of all the many and varied types”.9 Invitation letters to arts and performing groups were sent out, while the manpower and resources of government departments were corralled and mobilised. The police, for example, were put on notice for crowd control, while enquiries were sent to the Social Welfare Department to ascertain if welfare homes would welcome shows on their premises.10 Correspondence between ministries and agencies flowed fast and furious: Might the Department of Social Welfare be open to purchasing seven projectors and three Land-Rovers? Could the People’s Association host the concerts in their community centres?11

***

“When I approached the performers, I cut straight to the point—we didn’t talk about our differences, [but] tried to find similarities. That’s how I started organising performances.”12

Former Ministry of Culture officer Kuay Guan Kai (Guo Yan Kai) recounting how he convinced artists to perform in the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat concerts during a 2025 interview with the Founders’ Memorial

***

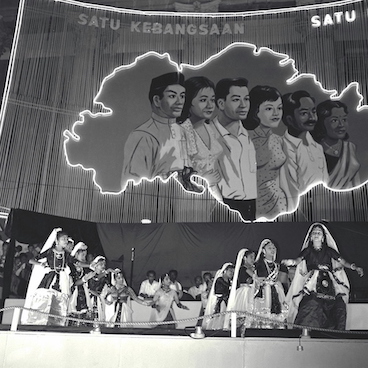

A letter from the Ministry of Culture to the Controller of Programmes at Radio Singapore, requesting for a list of Indian musical outfits for forthcoming Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat concerts, 29 June 1960.

Ministry of Culture Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

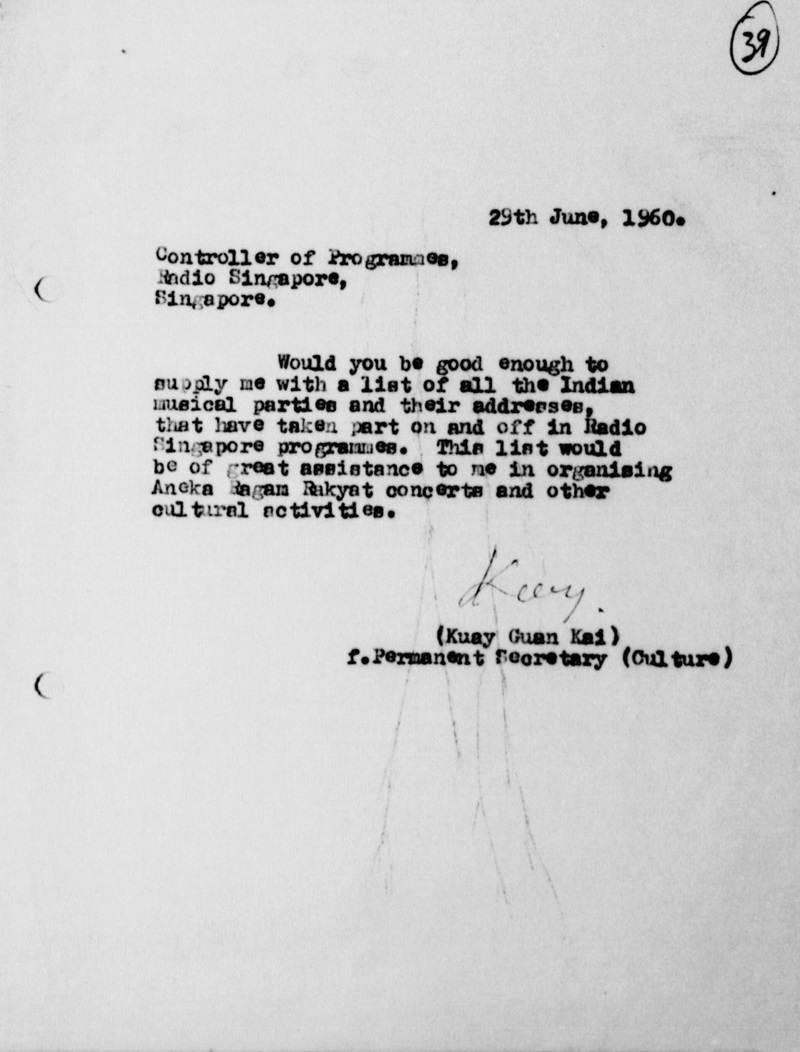

Archival records indicate that the response to this novel initiative was overwhelmingly positive. Performers ranging from lion dance troupes to sword-eating strongmen responded enthusiastically, with prominent cultural bodies like Bhaskar’s Academy of Dance and Malay Film Productions putting up performances, sometimes even without compensation.13 School-based groups from Nan Hua Girls’ School and the Tao Nan School Old Boys’ Association also stepped forward.14 Most significant of all was the distinctly multicultural way each concert’s programme was organised—to cite a specific example, a concert could open with the singing of Majulah Singapura by the Alice Wong Boys Choir, followed by a thread-weaving showcase by students from Vasugi Tamil School, and close with a mesmerising “flag dance” by Perpaduan Seni Ra’ayat.15 At the concerts’ inaugural run at the Botanic Gardens on 2 August 1959, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew leaned into this promising vision of an inclusive, multicultural Singapore. Labelling the concerts as “part and parcel of our search for a national identity”, he expressed his hope that “under open skies… Malays, Chinese, [and] Indians will discover the materials for a national art and national culture”.16

A handwritten letter in Malay from Mr Noor Ismail of the Al-Wardah Music Party to the Minister for Culture, requesting permission to participate in the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat concerts, 2 June 1960.

Ministry of Culture Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew speaking during the opening of Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat at Singapore Botanic Gardens, 2 August 1959.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

With public support for the concerts gaining traction, the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat wound its way across Singapore and its outlying islands, reaching locations as far-flung as Ama Keng, Changi, Pulau Bukom Kechil, and even the penal settlement of Pulau Senang.17 Oftentimes, the setup was simple and rudimentary, with a makeshift wooden stage complemented by an awning to provide shelter from the elements. The public, however, was undeterred. Thousands flocked to attend these open-air shows, often after a hard day at work in the farms, factories, offices, and kitchens.18 Vivien Goh, a pioneering violinist, music teacher, and impresario, who performed at an Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat concert at Katong Park, recalled that the concerts were “... something new. [They were a] different kind of entertainment. There [was] not much going on in Singapore at that time. It was free. I [thought it was] a fantastic idea for people to get together in an informal way. It was very primitive. Open air, no acoustics”.19

An Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat performance on the penal settlement of Pulau Senang, 16 October 1960.

The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

For the disparate performers who gathered to showcase their diverse crafts, the concerts were an opportunity to engage with a wider audience, as well as to mingle with like-minded arts practitioners. Dr Uma Rajan, an avid classical Indian musician and dancer who would later become Director of the School Health Service at the Ministry of Health, was one such performer. In a 2025 interview with the Founders’ Memorial, she connected her experience at these concerts with her ability to identify as a Singaporean: “The concerts brought me closer to all these cultures, made me appreciate these cultures more, understand them more, and even practise some of them... We knew each other, and we could draw on [each other’s] talents, and advice, and get [each other[ to perform at events… So I think Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat is what made me a Singaporean in the [truest] sense.”20

An Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat showcase at Bukit Panjang Community Centre, 24 January 1960.

The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Evaluating Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat

The enthusiasm and popularity of the concerts notwithstanding, one may argue that the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat did not in fact fully realise its lofty goals of creating “new and progressive [art] forms”, given that the permanent synthesis of different cultural outputs did not ultimately take root.21 Nevertheless, concert programme records reveal evidence suggesting organic, ground-up cross-cultural experimentation as artists interacted, worked, and learnt from one another.

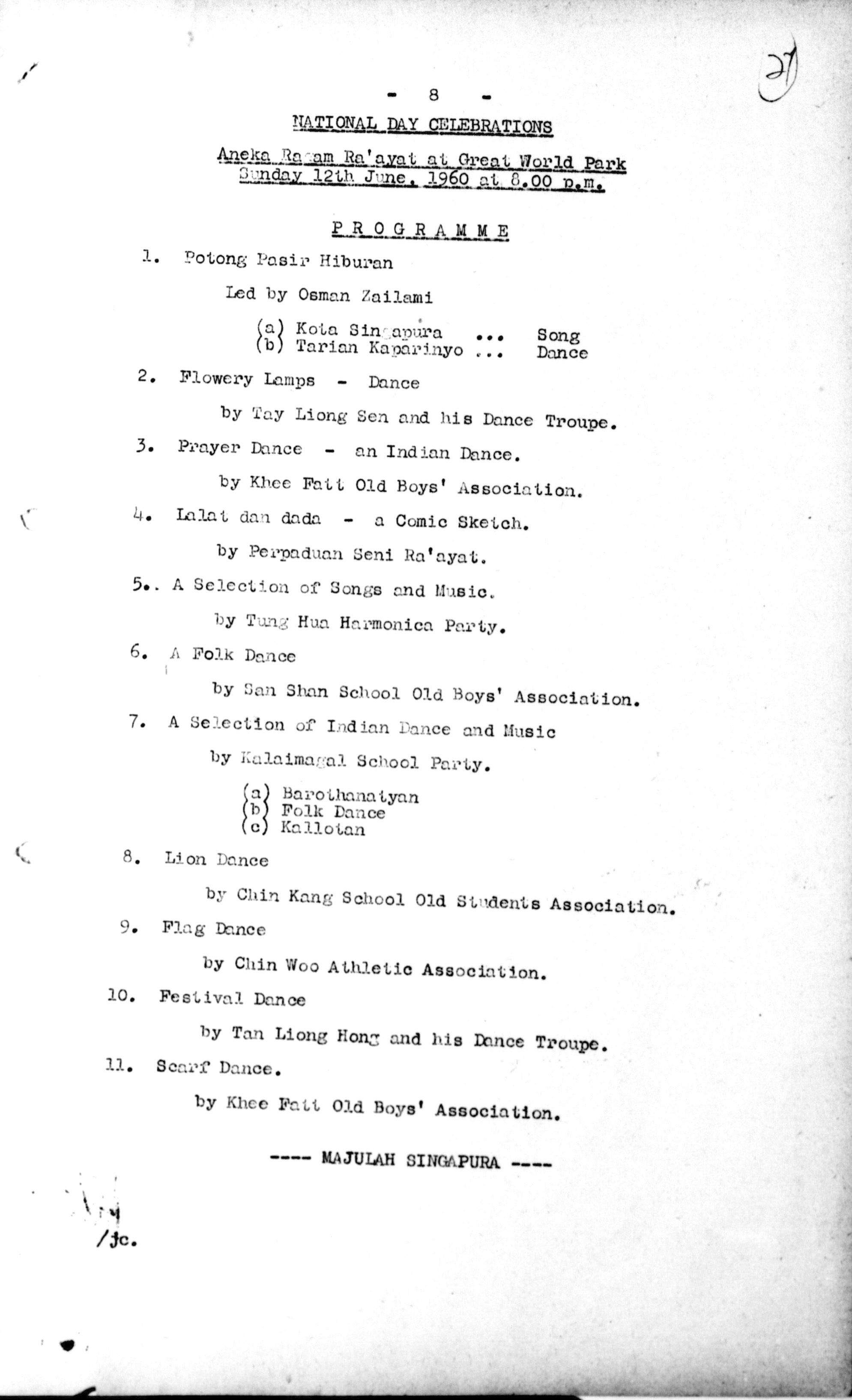

Programme for an Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat show at Great World Park, 12 June 1960.

Ministry of Culture Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

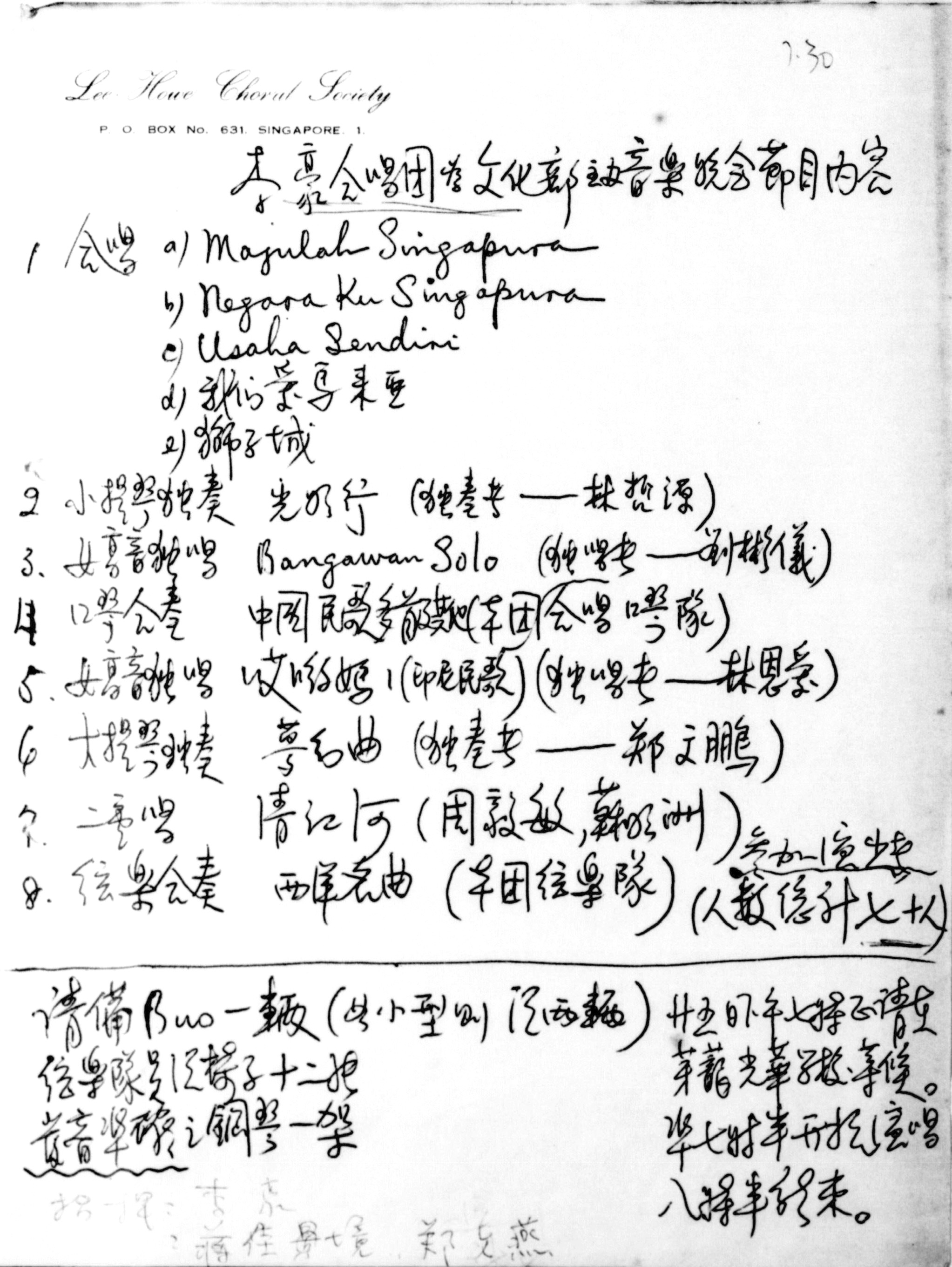

Handwritten programme by Lee Howe Choral Society, denoting a list of songs for an upcoming Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat concert, c1960.

Ministry of Culture Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

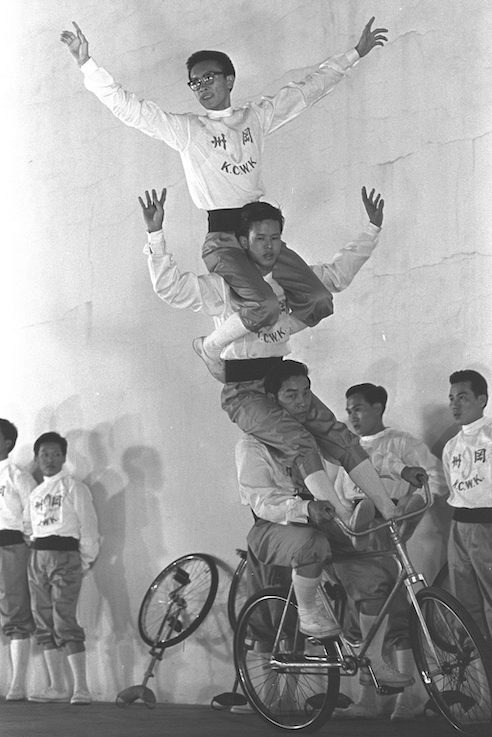

For example, in one instance in 1964, a Malay-based cultural outfit piloted a collaborative dance performance, Bersanding Suite, which “interpreted [a] traditional Malay wedding ceremony in a mixture of multicultural dance forms”.22 In another case, a singing troupe known as the Suara Singapura Singers took a leap to organise a multiracial choir—an initiative unusual at a time when monocultural art forms were prevalent.23 These aside, there were the perennial crowd favourites—strongmen acts, balancing and juggling routines, and fire-eating showcases—whose appeal cut across racial divides.24 While these outfits may not have systematically integrated different cultural elements into a coherent whole, these examples suggest that the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat had at least served to get people to come to “know and appreciate through the arts the ways of thinking and living of one another”.25

***

“I was so new, [I was] just about to learn dance, Malay dance. Just learning asli, inang, ronggeng, that kind of thing. And suddenly [after performing], [we would] see Chin Woo [Athletic Association]. Then we [would] make friends with Chin Woo, you know. Chin Woo Lion Dance. It’s behind the scenes that we created [a sense of] togetherness.”26

Som Said, pioneering Malay dance choreographer and Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat performer, in a 2025 interview with the Founders’ Memorial

***

An acrobatic troupe at the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat at Hong Lim Green, 6 February 1963.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Audience enjoying an Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat performance on Pulau Bukom Kechil, 25 October 1959.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

However, as the 1960s rolled on, it soon became apparent that cultural appreciation and intermixing—as lauded a goal as it was—could only be the first step in building a multicultural society. This was especially apparent as race relations frayed under the strain of Singapore’s entry into the Federation of Malaysia, catapulting the sober realities of racial politics, sectarian interests, and communal violence into the national consciousness. When independence was thrust abruptly on Singapore on 9 August 1965, the lofty goal of creating a unified Malayan culture—one requiring time, patience, and a dose of idealism—had to take a temporary backseat. Rajaratnam himself would subsequently reflect on the difficulties of creating a singular national culture during a speech in 1974: “It would be nice and convenient, of course, if a Singapore culture could be created overnight. There was a time when some of us thought it could be but the upsurge of tribalism, racial revolts, and religious fanaticism... is to us a warning that communal cultures tend to become more stubborn and violently assertive if attempts are made to destroy them from the outside.”27

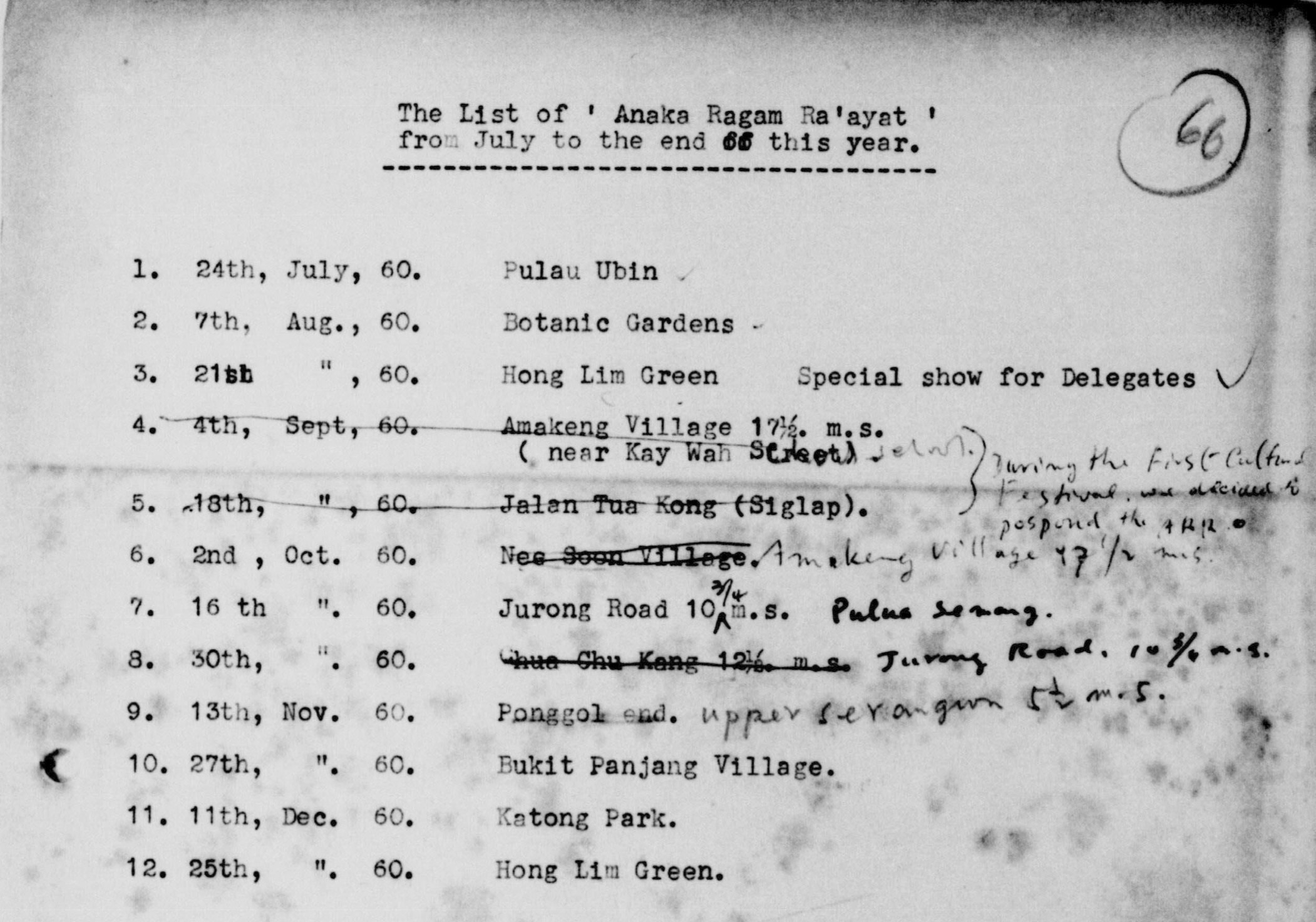

List of locations for Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat shows from July to December 1960.

Ministry of Culture Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Beyond Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat

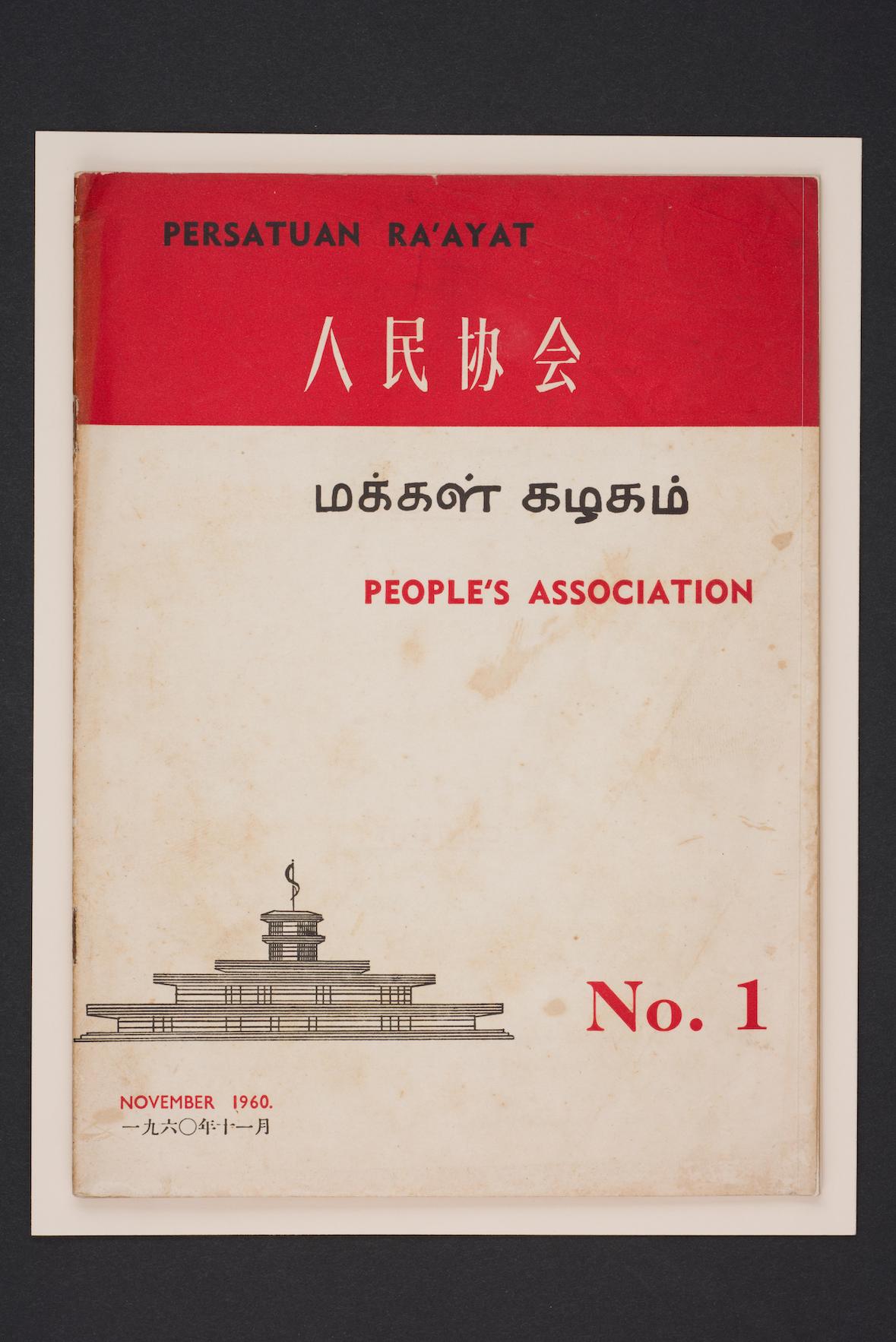

While the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat performances gradually faded away during Singapore’s first decade post-independence, its cultural legacy was continued by organisations like the People’s Association (PA), which had been formed in 1960, and whose community centres had played host to many Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat concerts. Tasked with promoting community involvement in social, cultural, educational, and sporting activities, the PA has worked with an array of grassroots cultural organisations to promote cross-cultural appreciation over the years.

Today, this network has expanded to include groups such as Perkumpulan Seni Singapura, which seeks to preserve traditional Malay culture, Er Woo Amateur Musical and Dramatic Association, which promotes Chinese Han music and opera, and the Singapore Indian Fine Arts Society, which actively organises music and dance concerts by local and visiting performers.28 More significantly, since the 1970s, the PA has played a central role in organising and promoting Chingay—currently billed as Singapore’s “largest street performance and float parade”. Originally a festival associated primarily with Chinese New Year, Chingay has since evolved into a colourful epitome of Singapore’s multicultural society, with annual performances bringing together troupes from different communities, ethnicities, and cultures.29

People’s Association publication No. 1, 1960.

Collection of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

The PA’s work in continuing to promote cross-cultural appreciation, even after Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat wound down, was especially significant given widespread fears in the 1970s that the blind embrace of Western culture would lead Singaporeans to forsake their Asian identities. By this time, Jek Yeun Thong had taken over as Minister for Culture, leading the Ministry in a new direction which emphasised the preservation of “ethnic and folk culture as a cultural ballast against alienation and Westernisation”.30 While there was, for a time, a stronger policy focus on promoting cultural forms deemed “proper and desirable”, in the long run, as Jun Zubillaga-Pow describes, “the vision of S. Rajaratnam was not lost”, especially since the Ministry continued its efforts to “preserve and develop [Singapore’s] cultural heritage derived from the main streams of the Malay,Chinese, Indian, and Western civilisations”.31 When the Member of Parliament for Aljunied Wan Hussin Haji Zoohri delivered his Parliamentary speech on a Bill to establish a National Arts Council in 1991, one could still make out the long-cast shadow of the early Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat in Wan’s eloquent homage to Singapore’s cultural identity:

“The dictionary explains ‘potpourri’ as a mixture of flowers or petals, herbs and spices, kept and used for scent or fragrance... It means that the different components of the flowers and the herbs in the potpourri can still retain their own properties, but together they contribute to the fragrance they exude. Using the same analogy, Singapore’s evolving culture and arts must be a potpourri or a mixture of the various ethnic cultures and arts with a strong strand of Western cultural tapestry woven into it. Such a mixture would bring forth a cultural fragrance which is distinctly Singaporean.”32

|

The Singapore Multi-Ethnic Dance Ensemble Started by Som Said, Yan Choong Lian, and Neila Sathyalingam in 1985, the Singapore Multi-Ethnic Dance Ensemble is a ground-up effort exploring the idea of a multicultural Singapore through dance. It is a powerful example of how the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat’s legacy continues, well after the concerts were discontinued in the mid-1960s. By cross-training students in Malay, Chinese and Indian dance, the ensemble brings together Singapore’s colourful and varied traditions, offering audiences a visual spectacle of unity in diversity.

Singapore Multi-Ethnic Dance Ensemble performing at Zhenghua Primary School for Racial Harmony Day, 2024. Courtesy of Sri Warisan Performing Arts Ltd. |

Postscript

“In the old days, we had Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat in the 1960s. Those of you who are old enough will remember—people went to different community gathering points to watch multiracial performances.... We can’t go back to those old days. But we can find new ways to now deepen our multiculturalism, encourage more criss-crossing—more collaboration between artists of our different cultures, and more individuals and groups crossing into each other’s cultures.”33

–– President Tharman Shanmugaratnam at the Spring Reception organised by the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations and the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre, 2024

Today, Singapore boasts a vibrant and pulsating arts scene. Diverse arts and performing groups continue to proliferate, and Singaporeans are engaging more intensely than before in events and festivals of various shades.34 While the sophistication and complexity of today’s arts landscape may seem a far cry from the makeshift stages of the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat, the latter is worth holding up as an exemplar of the bold vision of our early leaders. At a time when resources were scarce and the future uncertain, their very conception of a multicultural concert was a daring and radical act—one that brought the ideals and values of a newly emergent state into tangible, visceral, and visible form. Without their resolve and determination, the dream of a multicultural Singapore may well have remained just an abstract ideal, devoid of the life, colour, and energy that the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat first ushered in.

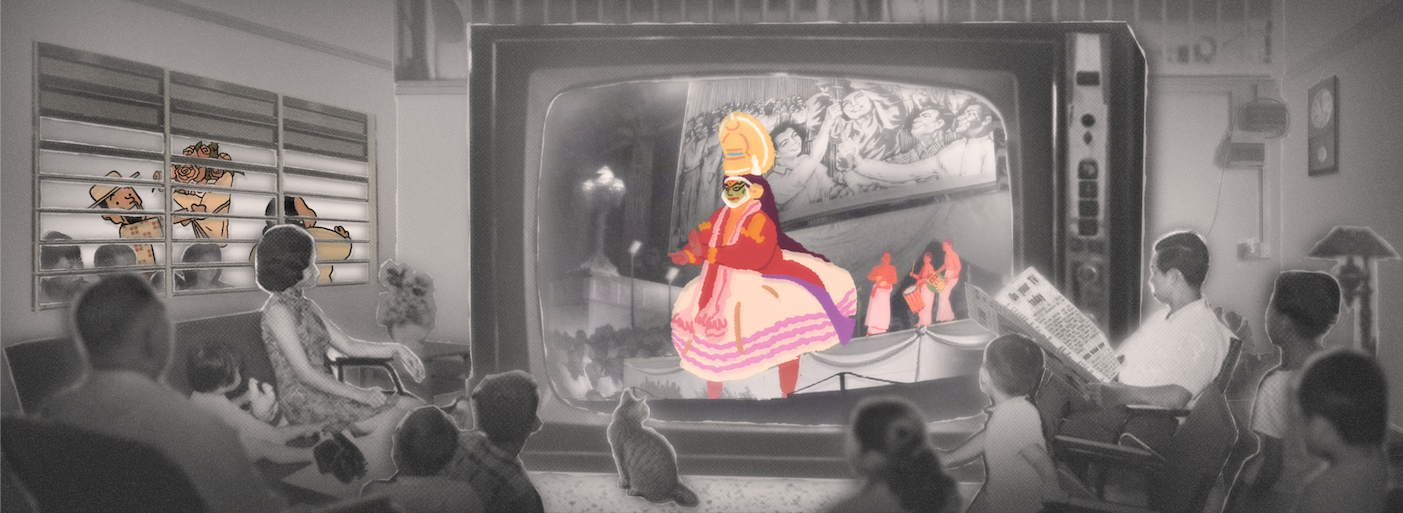

Stills from Finding Pictures’ animated short film Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat, commissioned by the Founders’ Memorial and on display in Not Mere Spectators: The Makings of Multicultural Singapore, 2025.

Stills by Finding Pictures, courtesy of National Heritage Board.

Crowd at Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat concert at Hong Lim Green, 6 February 1963.

Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

NOTES

-

Lee Hsien Loong, “Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s National Day Message”, The Straits Times, 8 August 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/politics/prime-minister-lee-hsien-loongs-national-day-message-2021-read-his-speech-in-full (accessed 7 August 2025).

-

Singapore National Pledge.

-

Norman Vasu, “Locating S Rajaratnam’s Multiculturalism”, in S Rajaratnam on Singapore: From Ideas to Reality, edited by Kwa Chong Guan (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2006), 130.

-

S. Rajaratnam, “Text of a Talk ‘Towards a Malayan Culture’ at the University of Malaya”, S. Rajaratnam Private Papers, ISEAS Library, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, SR.001.005.

-

Lee Kuan Yew, “Talk on ‘The Returned Student’ Given to the Malayan Forum at Malaya Hall London” (speech, United Kingdom, 28 January 1950), National Archives of Singapore, lky19500128.

-

Lee Tong King, “A Plethora of Tongues: Multilingualism in 1950s Malayan Writing”, Biblioasia (National Library Board), April-June 2024, https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-20/issue-1/apr-jun-2024/multilingual-languages-malayan-writing-sg/ (accessed 7 August 2025).

-

“Students Party to be Formed”, The Straits Times, 20 January 1950, 7.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 11, Sitting No. 3, Col. 133, 16 July 1959.

-

S. T. Ratnam to Permanent Secretary, 23 July 1959, Outdoor Cultural Shows Organised by the Ministry, National Archives of Singapore, MC 91-59 (hereafter cited as MC 91-59).

-

Permanent Secretary (Health) to Permanent Secretary (Culture), 19 December 1959, MC 91-59; Permanent Secretary (Culture) to Commissioner of Police, 8 September 1959, MC 91-59.

-

Notes on the meeting held in the Conference Room of the Ministry of Culture on introducing scheme for weekly entertainment in Community Centres and Youth Clubs in Singapore, 12 August 1959, MC 91-59.

-

Guo Yan Kai, interview by Founders’ Memorial, 5 June 2025.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 11, Sitting No. 17, Col. 1095, 13 December 1959; Jun Zubillaga-Pow, “Government Policies on Music”, in Singapore Soundscape: Musical Renaissance of a Global City, edited by Jun Zubillaga-Pow and Ho Chee Kong (Singapore: National Library Board, 2014), 204.

-

“18th Presentation of the Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat by the Ministry of Culture to be Held at Ama Keng Village”, 2 October 1960, Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat General Correspondence, National Archives of Singapore, 865/59 (hereafter cited as NAS 865/59).

-

“17th Presentation of the Aneka Ragam Raayat by the Ministry of Culture to be Held at Hong Lim Green Regional Theatre”, 21 August 1960, NAS 865/59.

-

“Lee: We’II Breed New Strain of Culture”, The Straits Times, 3 August 1959, 4.

-

“Lee: We’II Breed New Strain of Culture”.

-

“Concerts for Culture”, The Singapore Free Press, 4 June 1960, 7.

-

Vivien Goh, interview by Founders’ Memorial, 15 November 2024.

-

Uma Rajan, interview by Founders’ Memorial, 5 December 2024.

-

S. T. Ratnam to Permanent Secretary, 23 July 1959, MC 91-59.

-

Programme for Solidarity Night Concert for the National Solidarity Week Rally at the National Theatre on 17 November 1964, Report on Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat and Other Concerts, National Archives of Singapore, 119/64.

-

“Cultural Show in Honour of his Excellency The President of the Republic of Italy at the Istana”, 1 October 1967, Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat General Correspondence, National Archives of Singapore, 865/59PT.4

-

Programme for Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat at Geylang Serai, 4 June 1960, NAS 865/59.

-

S. T. Ratnam to Permanent Secretary, 23 July 1959, MC 91-59.

-

Som Said, interview by Founders’ Memorial, 17 October 2024.

-

S. Rajaratnam, “Speech at the Symposium on ‘Singapore Culture – Indian Contribution’ Organised by the Indian Fine Art Society of Singapore at Chinese Chamber of Commerce” (speech, Singapore, 28 July 1974), S. Rajaratnam Private Papers, ISEAS Library, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, SR.016.008.

-

“Member Organisations”, People’s Association, https://www.pa.gov.sg/our-network/member-organisations/ (accessed 7 August 2025).

-

“The Chingay Story”, Chingay Parade Singapore (People’s Association), https://www.chingay.gov.sg/about-us/the-chingay-story (accessed 30 December 2022).

-

Terence Chong, “The Bureaucratic Imagination of the Arts”, in The State and The Arts in Singapore: Policies and Institutions, edited by Terence Chong (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2019), xxiv.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 40, Sitting No. 14, Col. 1196, 25 March 1981; Zubillaga-Pow, “Government Policies on Music”, 210.

-

Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 58, Sitting No. 2, Col. 151, 28 June 1991.

-

“‘Deepening Our Multiculturalism’: Transcript of Remarks by President Tharman Shanmugaratnam at the Spring Reception 2024”, Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre, https://singaporeccc.org.sg/media_room/deepening-our-multiculturalism-transcript-of-remarks-by-president-tharman-shanmugaratnam-at-the-spring-reception-2024/ (accessed 7 August 2025).

-

Clement Yong, “8 in 10 Singaporeans Proud of Local Arts Scene: NAC Survey”, The Straits Times, 2 December 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/life/arts/8-in-10-singaporeans-proud-of-local-arts-scene-ac-survey (accessed 7 August 2025).

***

Pearl Wee is Manager (Education and Interpretation) at the Founders’ Memorial. She oversees education programmes and works to develop interpretive content. In her free time, she enjoys travelling and reading.

***

This article is featured in the Founders’ Memorial’s +65 publication, Volume 4 — the flagship publication that aims to build thought leadership on Singapore’s independence and post-independence history and society. This issue explores multiculturalism, offering broader context on its origins and evolution in independent and post-independent Singapore (1950s–1970s). Limited copies are available at the Not Mere Spectators: The Makings of Multicultural Singapore exhibition. Download your online copy here.